We are simultaneously two things that may seem to be in tension: We are who we are and have been, and, we are who we are becoming. The paradoxical conjunction between these statements challenges a prevalent social assumption, that personal identity is in some ways fixed.

Another observation to consider: We can no longer be who we were, years ago, nor who we thought we might someday become. For we are no longer who we were then, and surely not the person who we thought we might want to be as we matured.

But who we are now is the person we are becoming.

A trustworthy maxim from my field of ethics provides a reliable insight: practice shapes character. And character shapes practice. What we do shapes who we are (and who we are becoming), just as who we are shapes what we are likely to do. And a good definition of character is “a disposition to act in particular ways.” Our character is shaped by what we do, and what we do continues to shape our character.

Or, as Forrest Gump’s mama famously said, “Stupid is as stupid does.”

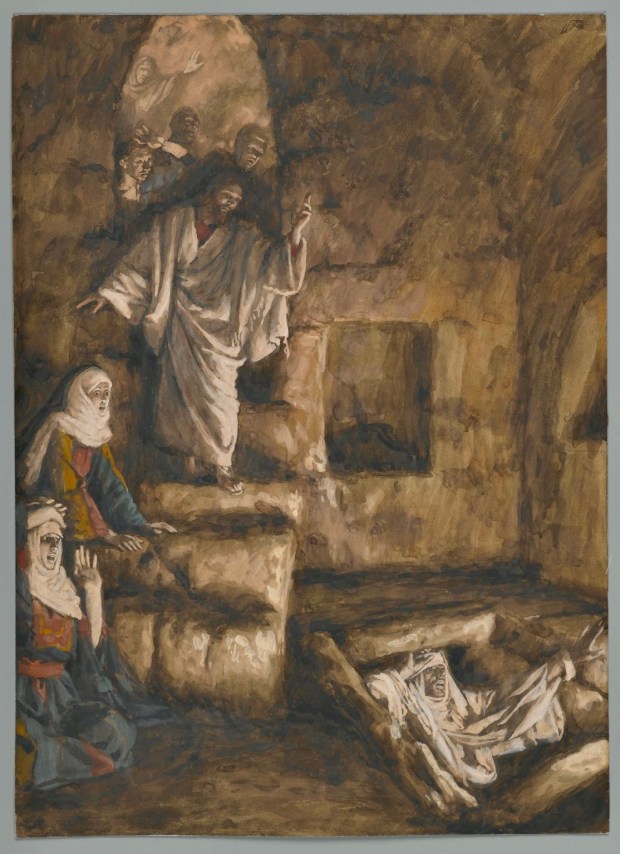

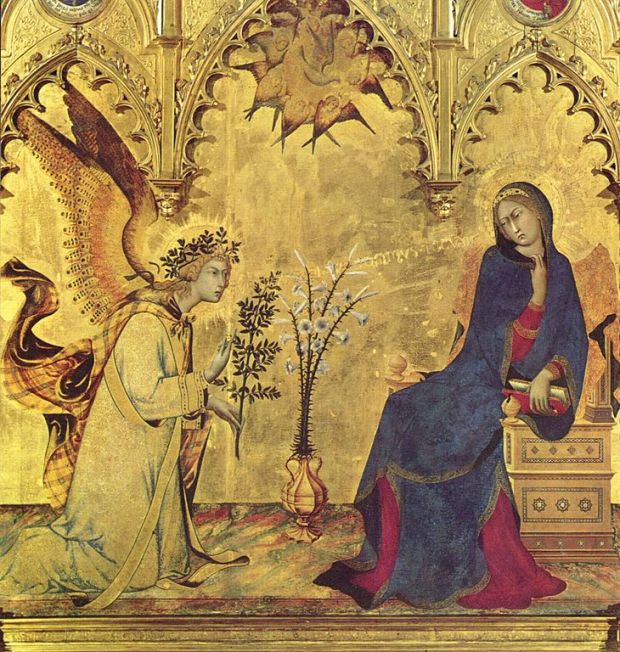

Whatever truth may be found in another old saying (“character is destiny”), who we are becoming is not in some way predetermined. We are in large part shapers of ourselves, even while we may feel like we are being shaped by events and or by other people. Yet, from the Beginning, God has been the Great Shaper of all things, even of us. As our Redeemer, through Baptism, God changes us and gives us a new life centered on the graced possibility of redemptive transformation.

In formal terms, the ideas I am exploring here involve dialectical relationships, such as we find between act and character, and between us and others. In these relationships, there is always a two-way, dynamic process of interaction between these various entities, whether we are speaking of God, ourselves, others, and or the circumstances in which we find ourselves.

Within all this, we experience a lifelong quest for a better sense of our identity. It is too easy, though often tempting, to try and resolve this quest in terms of external factors, such as who we imagine ourselves to be in the eyes and thoughts of other people. To be directed in our ideas and actions by what we think may be expected of us, or by what other people hope for us, usually comes at the expense of the influence of the Great Shaper, the One who reveals to us our true meaning and the purpose of our life journeys. Our primary dialectical relationship is with our Creator and Redeemer, our grounding guide for who we are meant to be, and become.

For these reasons, it is good to resist the typical kinds of “I am… “ statements so current in popular culture – statements like “I am a Democrat, or a Republican,” or “I am an introvert, or an extrovert.” A more helpful kind of self-definition springs from statements based on what we tend to do. For example, instead of the prior statements, it would help us to say things like, “I tend to vote in the following ways…,” or “I tend to respond to social situations by preferring to…” Consistent with these views, I resist self-definition in similar “I am” terms when it comes to how I measure when using Myers-Briggs related personal inventory instruments. This is, in part, because of their foundation upon Jungian thought, which anticipates how we as human beings have the opportunity to grow and change over time, especially in the direction of our ‘shadow’ strengths or areas of challenge.

I continue to value an insight offered by a former teaching colleague. In a conference he once said, “People don’t actually ‘learn from experience;’ they learn from reflecting on experience.” We experience and do things; we reflect on both, and we learn as we continue to think about what we encounter, and choose to do.” In the process, we are becoming who we are now.

Who am I becoming in relation to what I am doing now? This is a helpful Lenten question in light of our preparation for Easter living.