Perhaps people living at the time of our Lord’s first coming were in some important ways like us. They may have been just as prone to orienting their security and sense of wellbeing around material concerns, while being generally indifferent to the spiritual life. Yet, in this season of Advent when many sing “O come, O come Emmanuel,” it is easy to imagine the people of Roman-occupied Palestine crying out with longing for the God of Israel to draw near in power. Even so, God chose an out of the way place in which to appear among us, incarnate in human form. Paradoxically, for this and other reasons, the arrival of the Holy One was largely overlooked. At least until his person and message provoked enough reactivity to cause the authorities to have to deal with him. Otherwise, the periodic waves of public attention that he received were most often inspired by the miraculous works of mercy attributed to him. While he encountered significant examples of deference to the revealed Law among his contemporaries, lived-adherence to God’s hope-shaping promises appeared to be rare.

This is why the Lectionary features a particular aspect of the Christian Gospel story at this time of the year. It does this by presenting some notable counter-examples to what may have been – in the first century – a widespread indifference to or loss of confidence in God’s promises. We learn about Zechariah, the father of the ‘forerunner,’ John the Baptizer, and about Elizabeth, John’s mother, who was a cousin of Mary and another woman that would bear a promised child. These three stand out for having been open in heart and mind to the heavenly glory that God was about to reveal in the midst of the lives of his wayward children.

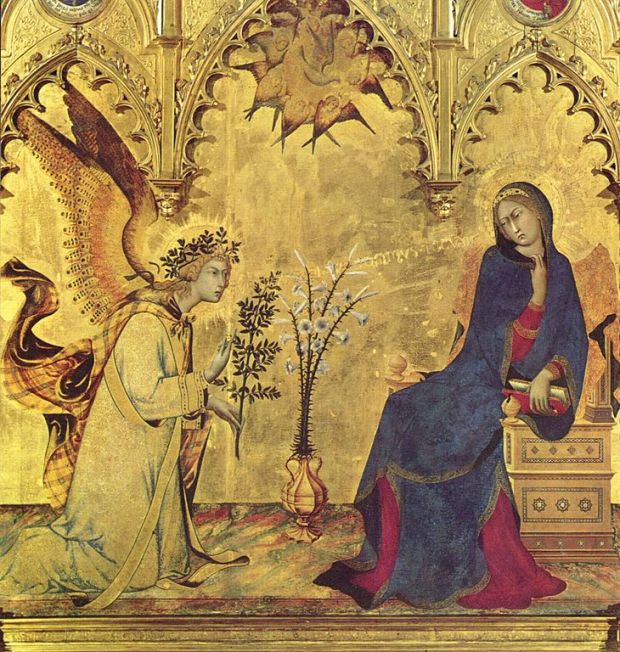

In particular we remember the spirit of attentiveness that we find displayed in a third aspect of Mary’s response to God’s call through the Angel Gabriel. God’s call often challenges us to live in a different way; or to try and be a different person, especially in our relationships with our family, our friends, and those with whom we work. Receiving this call, we can react at first in fear at what this call will mean in practice. We can also respond with uncertainty, wondering about our worthiness or suitability for what God may have in mind for us. We have reflected on these themes in the last two web posts on this site.

But we can also see that —in faith— we are able to go into the heart of our fear, and find God’s power. Receiving God’s grace, we may move beyond relying on our own strength, and resist depending upon our estimate of our own abilities and worthiness for what God may have in mind. And we can choose to respond to God’s gracious invitation to participate in the Spirit’s redeeming work, just as Mary did, by saying, “Yes!” As John Lennon so simply captured the spirit of it, in the words of his famous song, “Let it be!” As Mary said to God through the Angel, “Behold the handmaid of the Lord; let it be unto me according to thy Word.”

This is the spirit of Mary’s response to the message of the angel as portrayed in the third image I am sharing with you this Advent ~ Trygve Skogrand’s photo-collage, pictured above. The artist has skillfully placed a traditional painted figure onto a contemporary scene, juxtaposing an image of something old within a contemporary setting. We see a simplicity and spirit of humility in Mary’s posture, as she kneels in her plain gown. In the plain ‘bed-sit’ room in which she prays, we notice her uplifted eyes. They are now focused on the divine source of the message she is receiving.

Attentiveness is key to meaningful perception, just as we find in the Gospel reading for the third Sunday in Advent. John the Baptizer sends his disciples to Jesus with what should be our most persistent question ~ “Are you the One?” ‘Are you the One for whom we are looking, and whom we are awaiting?’ Notice Jesus’ response: “Go and tell John what you hear and see…” For they only hear and see if they are attentive. This is one reason why the Church sets aside this season of Advent ~ to encourage our attentiveness, so that we can hear and see, and then accept God’s Word to and for us.

“Let it be as God would have it.” Let things be as God wills. Let God be God! Perhaps nothing will be so hard in our lives, as to say those words in faith and in humility. Our pride objects. Our desire to be at the center of reality intrudes. But to say, “Let it be…,” in faith and in humility, is to return to the grace of the Garden of Creation. And it is also to begin to live forward into the fullness of the Kingdom, manifest in the New Jerusalem, as God will have things be.

The image above is a detail of Trygve Skogrand’s photo-collage, Bedsit Annunciation (one of my favorite artistic renderings of the Annunciation). This post is based on my homily for the Third Sunday of Advent, December 15, 2019, which can be accessed by clicking here.