In order to appreciate the beauty of tensile architecture, we need to remind ourselves of how most traditional buildings, from the ancient pyramids and China’s Great Wall through to the tallest modern buildings, have been built. Familiar architectural structures rely upon compression, the stacking of weighty materials upon others in a stable way to achieve height. Whether those materials are heavy, like the massive stone blocks supporting the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, or as in the first modern reinforced steel ‘skyscrapers’ such as the former Home Insurance Building in Chicago, traditional architecture has relied upon the compression of forces created by their materials to attain successively higher elevations over the course of time.

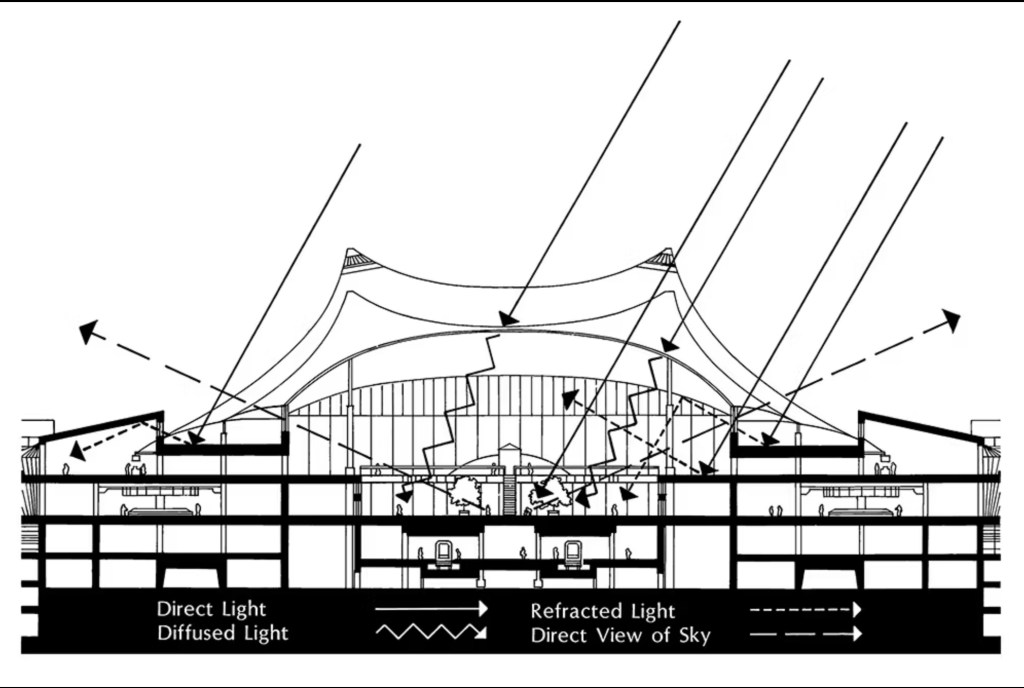

Tensile architecture relies upon what its name suggests in order to attain stable and enduring structures – the dynamic of tension between the various materials and structural elements that are employed. The way that tensile structures achieve what appear to be daring results can be explained by reference to the poles and cables with which they are constructed.

Though the name for this type of structure may be new to many of us, those who enjoy viewing sporting events set in large public spaces have seen and become visually familiar with tensile structures at least since the 1972 Olympics in Munich, Germany. Designed by Frei Otto and Gunther Behnisch, the imaginative canopy protecting much of the crowd seating was seen by millions on television and in news reports.

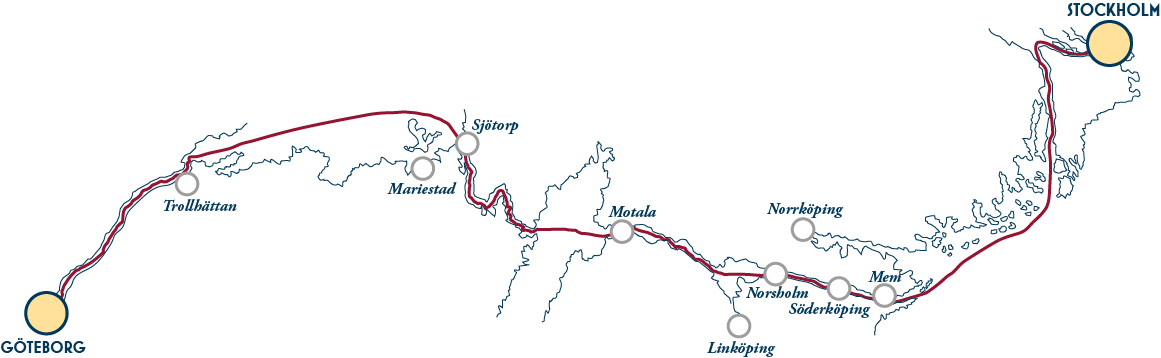

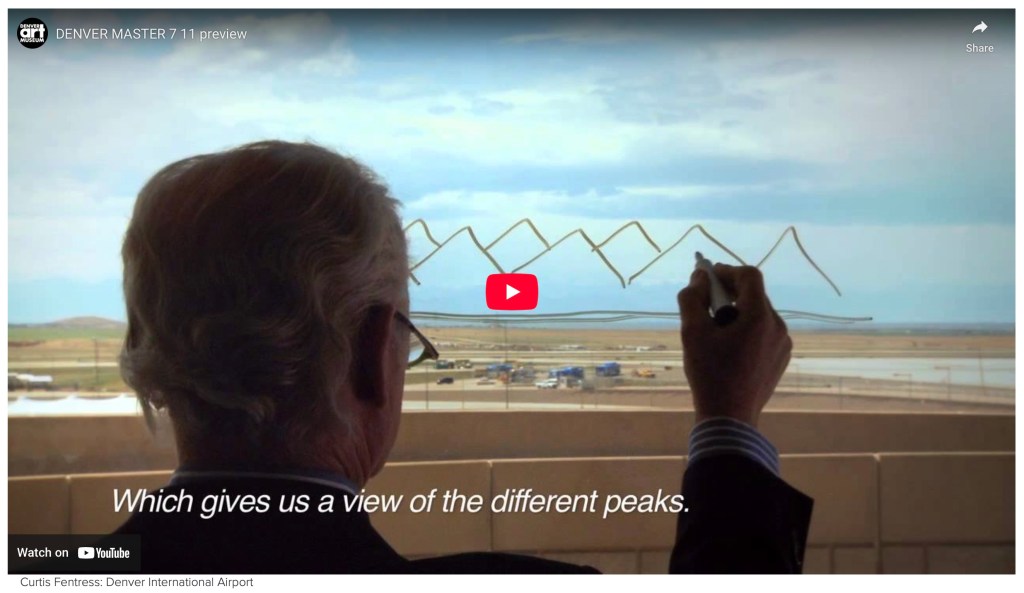

Tensile architectural design continues to be used widely throughout the world to erect buildings for public purposes. Denver’s 1995 International Airport Terminal building, designed by Curtis Fentress and Fentress Architects, provides a compelling example. The architects’ achievement represents a stunning contrast to Denver’s former and very conventional Stapleton AirPort buildings.

Those who travel through DIA have an opportunity to experience firsthand what such structures can inspire. They provide occasions on which we can pass through public spaces filled with light, that feel open and uplifting, and which have the capacity to capture our attention. Buildings of this kind expand our sense of the moment in community with others, and lift us above our personal concerns by reminding us – literally- of more expansive imaginative horizons. As the venerable great dome of the US Capitol building gives convincing evidence, these are qualities to which all public architecture should aspire.

Three thematic sources of inspiration for Curtis Fentress’s design for the DIA terminal include Denver’s well-known reputation for being the ‘mile high city,’ the profile of the Rocky Mountains visible from the terminal and the city, as well as the heights to which modern aviation take us. As the images included here demonstrate, the airport’s tent-like awnings create a dramatic roofline, as well as soaring translucent interior ceilings, delighting both visitors and passengers, as well students of architecture who have never traveled to encounter these structures.

Since my first visit, the Denver Airport has been one of my favorite examples of modern public architecture, both because of the vision and notable aims of its principal architect, as well as because of the experientially transformative results he and his team of designers and builders were able to achieve. Like the pleasing effect of arriving at London’s St Pancras or one of the other luminous Victorian train sheds, the DIA terminal is the kind of humane environment that can ameliorate the stress of modern-day air travel.

Note: I hope to feature Denver’s new (2014) canopied train platforms, perhaps inspired by the DIA terminal, in a future post.