If reading this by email, please tap the title at the top to open your browser for the best experience. Then, clicking individual pictures will reveal higher resolution images.

We live in a world filled with “data.” Disconnected bits of information, especially in great quantity, overwhelm our ability to see and to think. Accumulating additional data or more information does not produce knowledge. Knowledge has to do with seeing the connections between bits of information. When we see the connections, we begin to see a picture, we begin to hear a story, and we gain understanding as well as wisdom.

The unrecognized fellow traveler on the road to Emmaus asks the two disciples, ‘what are all these things you are talking about?’ The answer he receives from them amounts to information. But his question is pointed toward understanding, especially in relation to ‘the big picture. He is challenging them to discover something bigger. He is really asking something like this: ‘All these things’ that have happened… What do they have to do with what God has been up to, all along?”

Here is a basic Christian truth that we find in the Emmaus Road story: Things take on meaning in relation to the risen Jesus. It happens when we see events in our lives in relation to him. It happens also with things like bread and wine as we gather at table. And it happens with people like you and me as we gather in community.

Jesus helps our perception on the road to Emmaus, and reveals something even more profound at the inn. This ‘inn,’ unlike the one where he was born, has many rooms, many mansions. When we see things like past events and the bread in relation to him, we discern more about what they were or are, and what they yet can become. When we see ourselves in relation to him, we better discern who we really are, and who we are called to be.

Prayerfully, we can look around, between things, and within. We can look for the connections. When we do, we see and discern. We see more because we see more wholly. Then we see the holy.

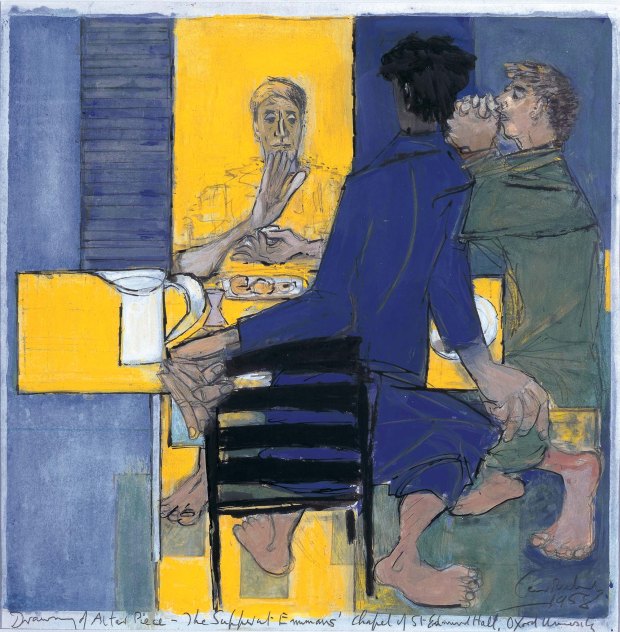

The above painting, Supper at Emmaus (1958), is by Ceri Richards, and is used by permission from the Trustees of the Methodist Modern Art Collection (UK). The penciled notation at the base of this guache painting on paper suggests that it was intended as a study for an altarpiece painting for the chapel of St. Edmund Hall (or College), at Oxford, England. The Emmaus story can be found in Luke 24:13-35, and it is a traditional Eastertide Gospel reading.

This post is adapted from one first published in 2014.