Recently, the Lectionary included a familiar reading from Genesis (chapter 32). It describes Jacob’s dilemma concerning his brother, Essau, from whom he is alienated. Alone at night in the wilderness, Jacob lays down on the ground and places his head upon a stone to sleep. In the darkness, Jacob then contends with an angel in what becomes a wrestling match that lasts through much of the night.

In parsing the elements of this deeply symbolic story, we must remember that in much of the Old Testament, angels appear and act as divine representatives. They also function as a literary device where the angelic figure is a stand-in for God. This is why it is appropriate to read this passage as a story about Jacob wrestling with God, as well as the more literal reading of it as an account of his wrestling with an angelic being. In either case, we are right to understand that the story portrays Jacob’s struggle to discern, and then accept, God’s will for him and for his future.

We are told that Jacob is fearful about meeting Esau, who is traveling with a large band of men. For, as we may remember, Jacob has wronged his brother by ‘stealing’ Esau’s birthright blessing, which Esau was to have received from their father, Isaac. As recorded in a well-known earlier story, Jacob had deceived their aged father by masquerading as his twin brother, who was only-minutes-older than him, thus receiving the blessing that Isaac had intended for Esau.

Now, with our modern understanding of psychology, contemporary readers of the nighttime angelic wrestling story may prefer to understand it as simply a symbolic portrayal of Jacob’s wrestling with his conscience. Though partly true, accepting such a univocal reading of the story comes at the expense of a profound dimension of the narrative. For this episode is what students of the Bible call a ‘theophany,’ a story about divine self-revelation, as Jacob himself (as well as the narrator) understood it to be.

So how might we appreciate this story of a nighttime struggle, involving unresolved aspects of a particular person’s history having to do with family relationships, as well as recording a pivotal moment within his long term quest for divine guidance?

I find it helpful to read the story within the following interpretive framework. When we refer to ‘struggling with God,’ I believe that what we often mean is our struggle to accept what we perceive to be (or suspect is) God’s will for us. As such, it has much to do with our understanding of prayer.

As I noted in a recent post, our Prayer Book teaches us that prayer is first of all a matter of responding to God. Responding to God, and responding to our perception of God’s will for us, are not often automatic or straightforward activities. Our natural disposition may be to fall back into thinking of prayer as enacting our desire to bring God’s will into accord with our own wants and hopes. For our prayers may often take this form. Yet, prayer is most holy when prayer is pursued in a way where we give ourselves up to an acceptance of our real need, not our wants. This is to accept our basic need for our wills to be brought into accord with the divine will. When this comes to be our more usual pattern of response to God, we are less likely to find ourselves having the feeling that we are struggling with God, and more likely to experience the peace of living harmoniously with God’s hopes and plans for us.

When the Genesis story refers to Jacob’s having prevailed we will do better than to settle for the conclusion that he has ‘won’ or achieved a goal. Jacob hung on to the angel; he did not let go. And in the process he came to have a limp, the struggle having dislocated aspects of his prior way of being. The limp was therefore less a sign of an injury and more a sign of a deep change within him, and within his mode of engaging the world that lay before him. Jacob could then utter his famous words: “For I have seen God face to face, and yet my life has been delivered.” Encountering God’s awesome and holy presence did not consume him as fire would dry tinder. Instead, Jacob was transformed, and received a new name, Israel.

Responding to God – and God’s will for us – with acceptance, will likely disrupt aspects of our present ways of living. And we may feel that some important parts of our lives, even of ourselves, have been dislocated in the process. But if we cling to God, even through the feeling of struggle, with the aim of coming to be more fully in accord with God, and God’s ways, we will be blessed, just as Jacob was.

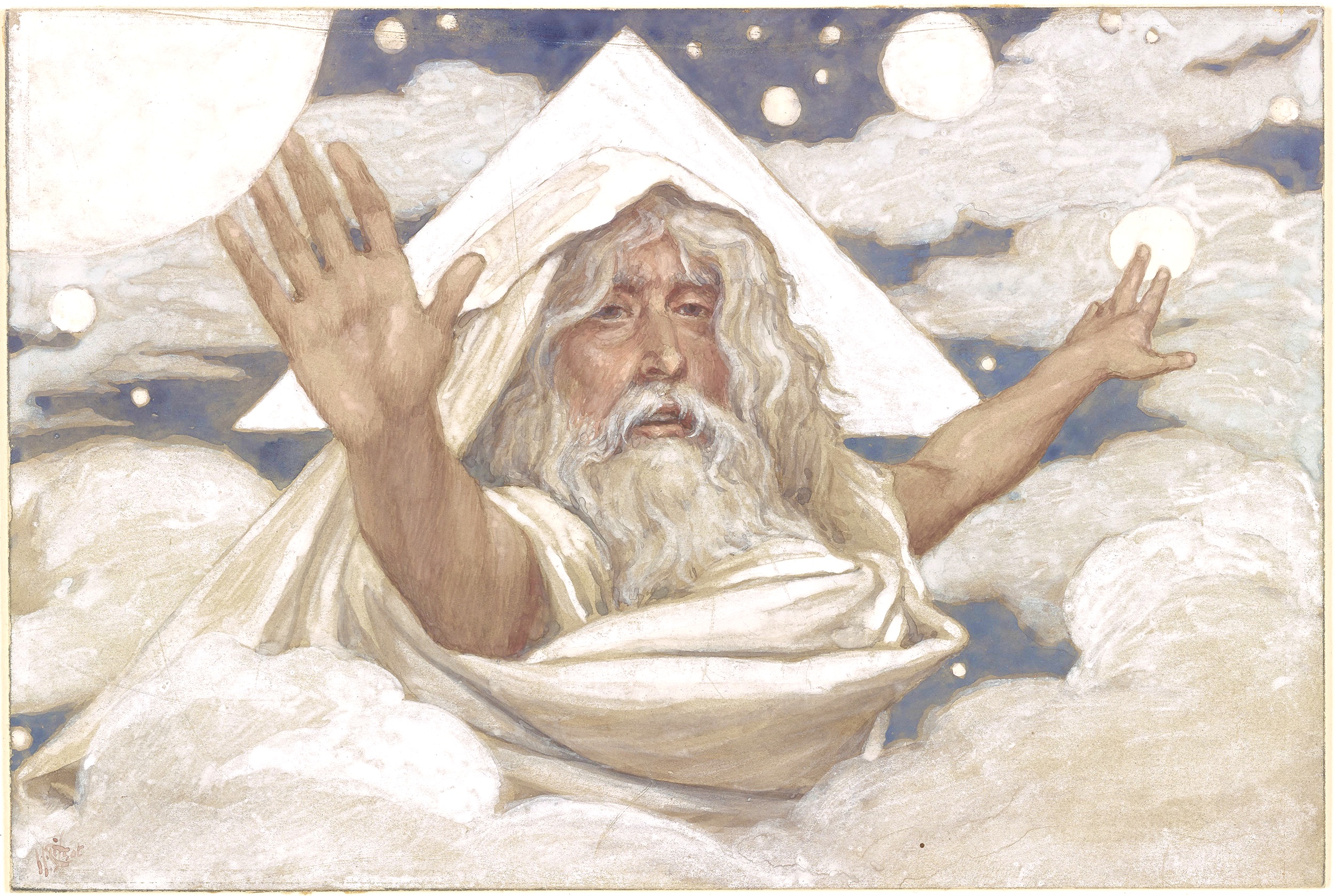

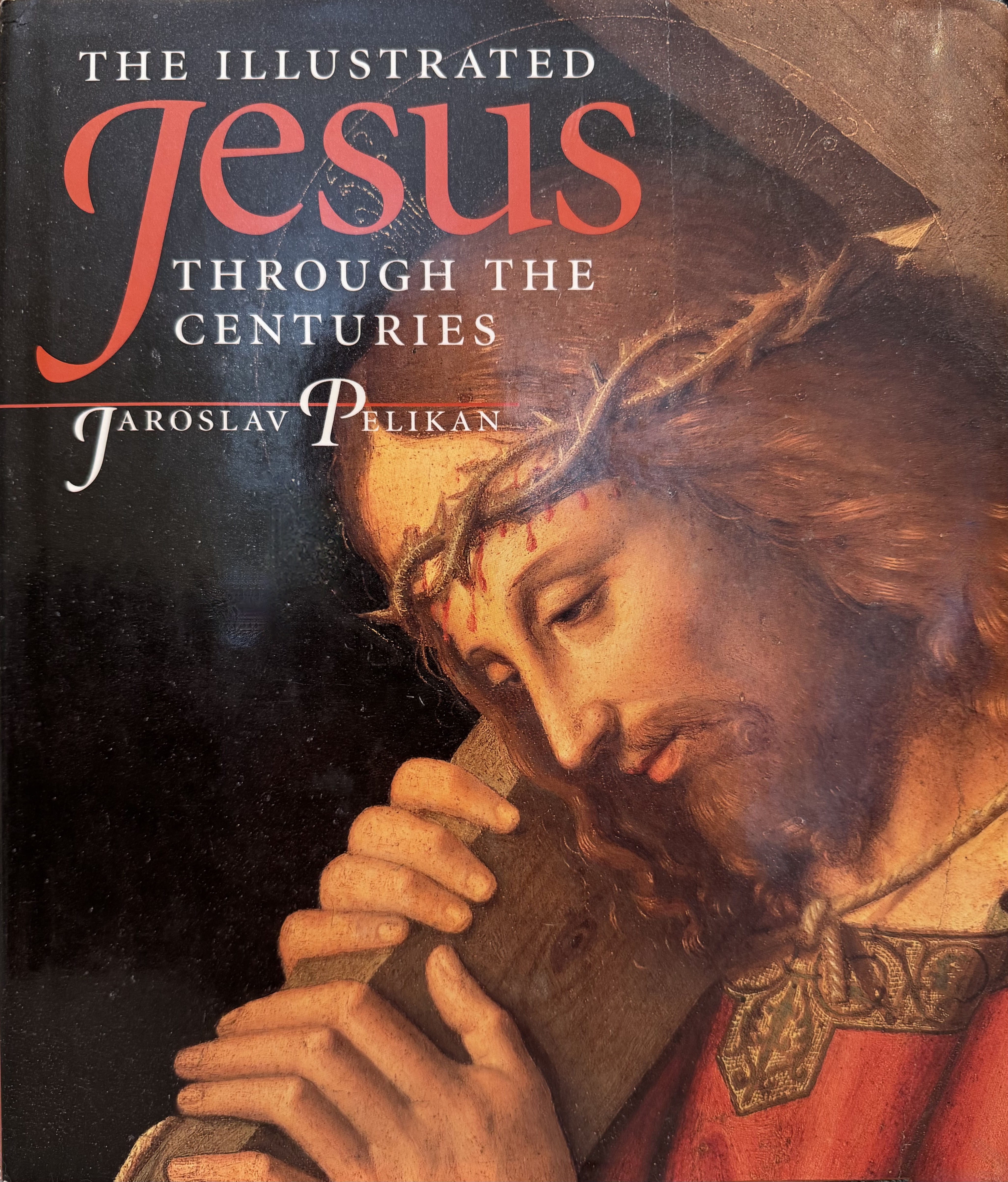

Note: among the many symbolic elements in Chagall’s painting, shown at the top, you might see if you can discern elements of the larger context of Jacob’s story, including those related to Joseph, in Genesis.