(Note: At the time of publication, what has happened to Nancy, the mother of Samantha Guthrie, is still unclear.)

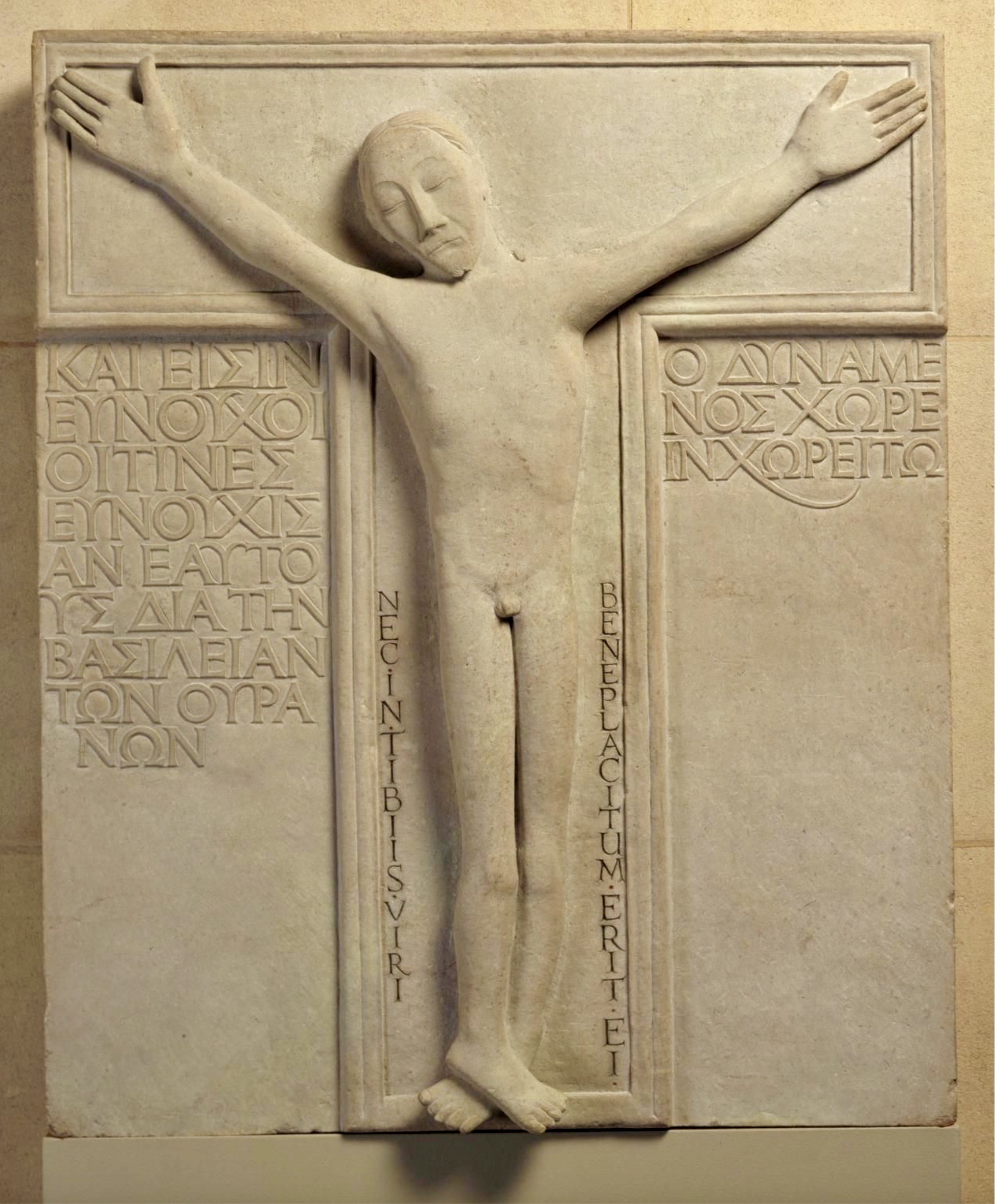

The beginning of Lent offers us a stark reminder of our mortality, and of our ’nothingness’ apart from God’s Grace. This may lead some of us to be mindful of the death that we fear, or the deaths of loved ones whom we mourn. Our observance of ‘a holy Lent’ provides a season when we can grow in our assurance of the New Life we are given in and through Christ. This happens through our Baptism into his death and Resurrection. The Easter season that lies ahead has much to say about this, which is one reason we might devote ourselves to particular disciplines of preparation during these Forty Days.

I want to approach this theme in light of the recent widespread publicity given to the abduction of Nancy, the mother of Samantha Guthrie. This tragedy has focused a great deal of attention on some words that she and her siblings have used with reference to their mother: “We believe she is still out there.” This cautious statement has been oft-repeated by law officers and the news media.

We hear these words in the context of learning that Samantha Guthrie has been a member of St. Philip in the Hills Episcopal Church, in Tucson, where a prayer vigil was offered on behalf of her mother. Samantha has also written a book in which she expresses her Christian faith, a fact also evident in some of her recent public communications.

For Christians, our loved ones are always ‘still out there.’ I want to offer some reflection on this phrasing, and explore what the Guthries’ quoted words may mean in terms of Christian belief.

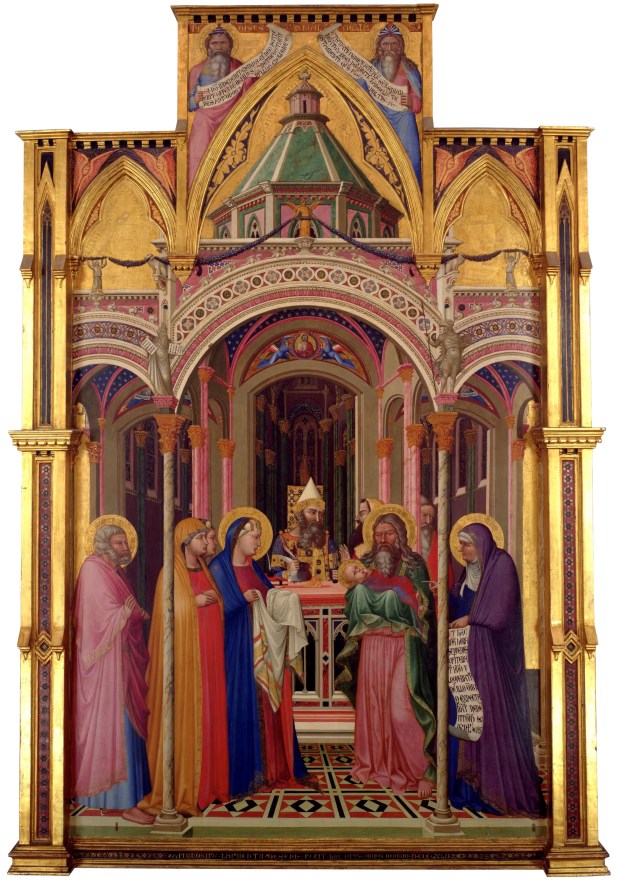

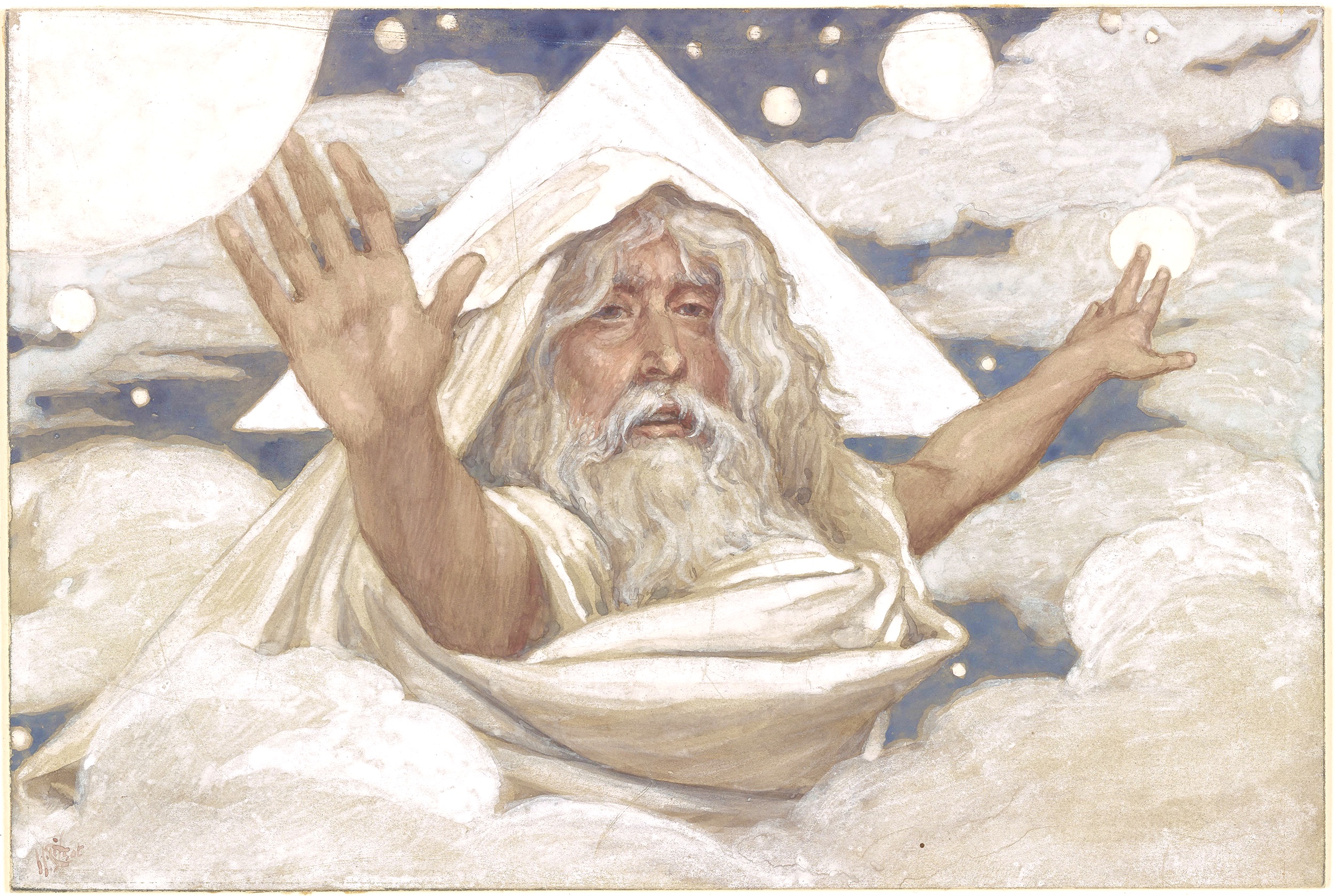

Despite a common notion we sometimes encounter in popular culture, people who die do not become ‘angels.’ Nevertheless, traditional Christian faith teaches us that angels are like us in reflecting a divine attribute, personhood. For we believe in One God in Three Persons (the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit). This is the mystery of the holy Trinitarian nature of God, in whose image and likeness all persons have been created. From our knowledge of God, and our experience of ourselves, we know that an integral feature of personhood is being in relationship with other persons.

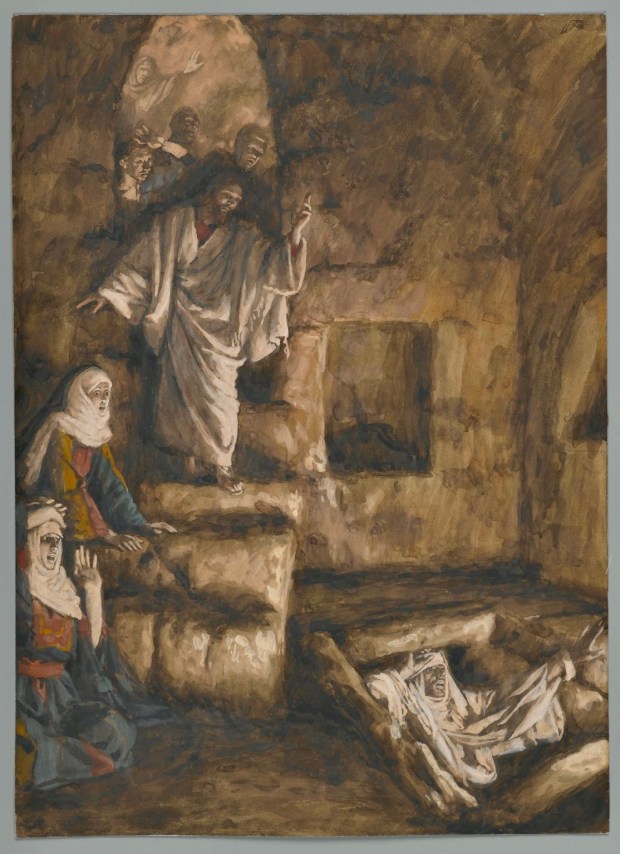

Yet, unlike angels, we are embodied, and remain embodied regardless of our transformation through the resurrection of the dead at the end of our mortal, physical, lives.

Since the time of the New Testament, Christians have spoken about this transformation into a new form of embodiment by employing various metaphors. In view of this, at our demise, we do not become like a drop of water returning to the sea, or move from a personal identity based on our differentiation from others into an unconscious and undifferentiated state of life. As if – at death – we will somehow be dissolved into a greater realm of ‘Spirit.’

By our Baptism into the death and Resurrection of Jesus, we become named members of His Body, the one Body of Christ. This is the Church in its essence, which comprises the communion of all the Baptized, whether they are ‘on this side of the veil’ or have gone before us to the next life. Thus, though we (as Anglicans) do not pray to saints, we pray with them as the Holy Spirit enables this activity within us. Those presently alive in this life and those who have ‘gone before us’ – are both ‘here’ and ‘there,’ in a shared living stream of ongoing prayer and fellowship.

An oft-neglected article of traditional Christian faith is that of the Ascension of our Lord, directly tied to his Resurrection from the dead. In our faith, Christ did not ‘go up’ alone, but carried with him our human nature. This enabled our own transition – with him – into the next life. When we die, by Grace we move into a greater experience of nearness with our Lord, who is already with us, and in us. Therefore, we do not cease ‘to be’ at death. And we are taught not to fear physical death in view of our belief in the significance of our Baptism into Christ’s death and Resurrection. By virtue of this Ascension-fortified faith, we have assurance about our continuing fellowship with those who have died “in the Lord.”

In view of these fundamental aspects of Christian believing, we can recognize how Nancy Guthrie continues to be among us, and always will be, regardless of what may have happened to her in the recent tragic circumstances now so familiar to us. For as Jesus is quoted as saying, in John 11:25-26, “I am the resurrection and the life. Those who believe in me, even though they die, will live, and everyone who lives and believes in me will never die.”

Note: I present these reflections without implying that my words here have negative implications regarding those who do not share our faith nor our baptismal identity. As for people whose faith (or lack of it) is known to God alone, we need to remind ourselves that, in God’s Providential wisdom, the divine will for those who do not identify as Christian remains a mystery to us.