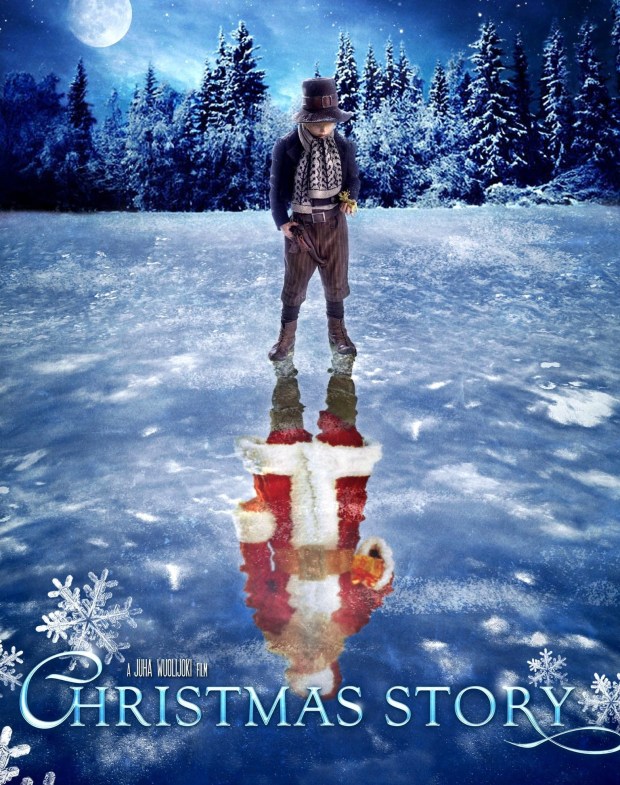

I was in college in the 1970’s. Though at first I was an agnostic art student while attending two Lutheran liberal arts colleges, many of my friends and two housemates were religion majors. This was at a time when the curricula for religion majors still included courses in Bible and in fundamental theology. Paul Tillich’s three Systematics volumes were still much read, as were Bonhoeffer and Barth. And Martin Buber’s once better-known book, I and Thou, was often recommended as a reading for various liberal arts majors.

The significance of Buber’s book was something I only came to realize much later, after grappling with Jean Paul Sartre’s rather dark, or as some would say ‘more realistic,’ view of human relationships. Those familiar with Sartre’s play, No Exit, may recall a phrase penned by Sartre, “Hell is other people.”

As I remember it, Sartre had in mind our experience of ourselves as being regarded by other people as an object. For Sartre, we function primarily, and are aware of ourselves, as subjects – subjects who resist being seen as the objects of other person’s perceptions and especially their judgement. Only later did I perceive the paradoxical affinity between the views of Sartre and Buber. For both were sensitive to the experiential problems that arise when people feel they are regarded as objects rather than as fellow-subjects. It is no coincidence that the lifespans of Buber and Sartre overlapped.

How hard it is for us then, spiritually and in religious terms. to be open to a related idea. For we find it difficult to experience and therefore to accept ourselves as being an object of God’s love. To see ourselves in this way is understandably uncomfortable for us, given how our fundamental way of living and of perceiving ourselves is to function as subjects who regard, come to know, and evaluate everything as an object of our perception – even and more especially, other people. And yet, as one of John’s New Testament Letters teaches us, we were first loved by God… before we were aware of it, much less come to believe this as true or live by it.

In view of these observations, we might want to invert Sartre’s rhetorical phrase regarding how our experience with other people can be ‘hellish.’ We might also say that for religious believers and especially Christians, our fellowship with other people may provide us with real experiential glimpses of what has traditionally been meant by ‘heaven.’

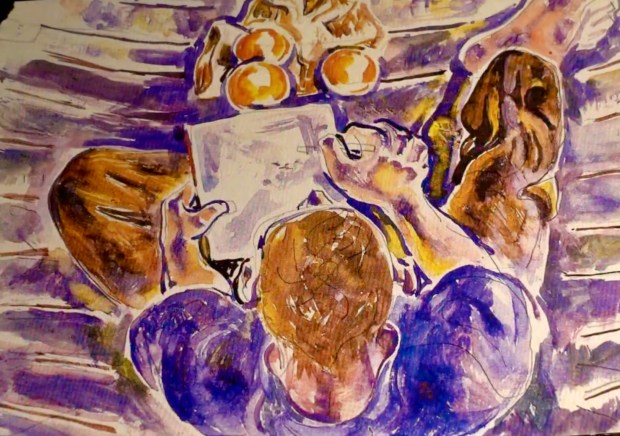

Here we can employ another often superficially-used phrase about certain experiences as being moments of ‘heaven on earth.’ With that phrase, we may need to expand our perception of ourselves in this way: Consciously and intentionally we want to live as an object of God’s love, of God’s enduringly positive regard and embrace, within God’s shared Trinitarian-fellowship. To see ourselves and others, as well as then to live, in this way, may require us to cease to think in terms of subject and object in a binary, either/or way. We learn from Buber that with one another we can be “I and Thou.” And each day, when first emerging from sleep, we can begin our morning with prayerfully re-orienting words like these: “Regardless of what I may have dreamed, Thou art, and as a result, I am.”

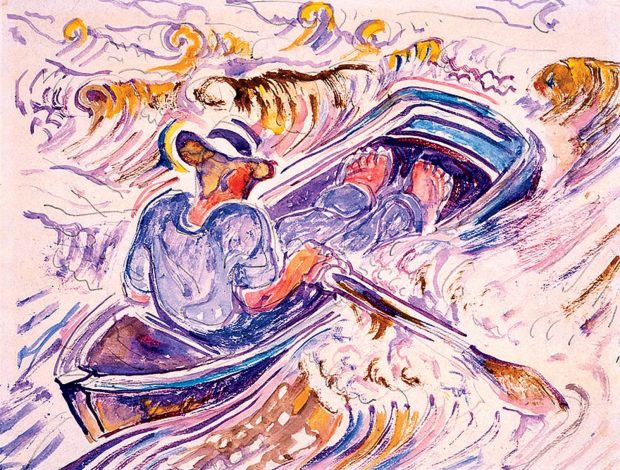

For as Jesus promised, saying, “Because I live, you also will live. In that day you will know that I am in my Father, and you in me, and I in you.” (John 14:19-20). Every day can be, and is, that day.

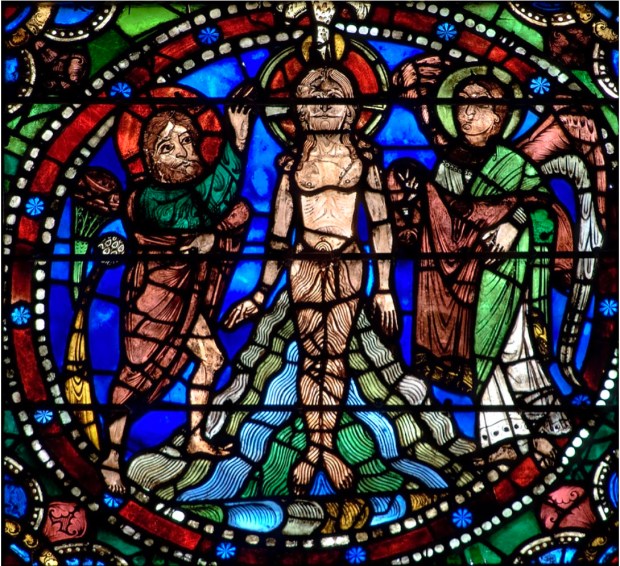

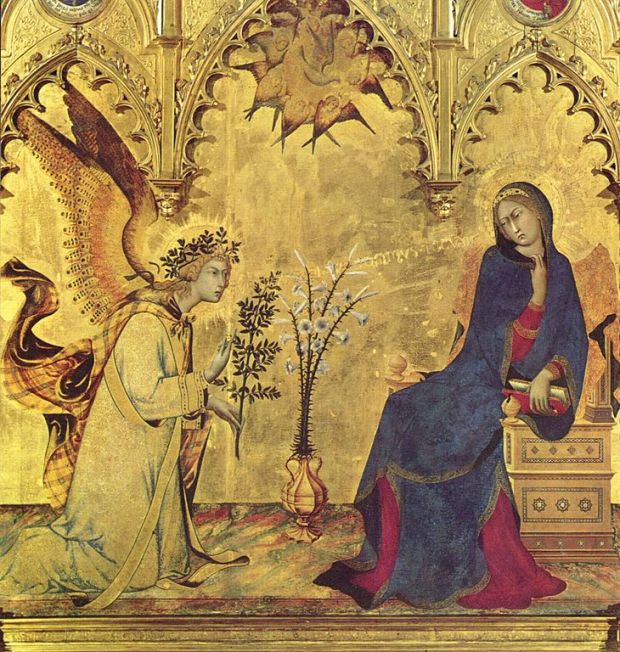

Our Baptism recalls Jesus’ Baptism, for both function – in part – as moments of designation. For us, it is the sacramental act when we are told that we have been included among God’s own children, made a part of Christ’s Body, and named for the community by the celebrant. In all these ways, we are the objects of God’s redemptive work through Christ and in the power of the Holy Spirit, by means of the Church. God chooses us before we are ever aware of our choice to respond.

“I recognize Thou, who first knew me before I ever became conscious of myself. Thou first loved me before I ever felt a challenge to love myself.”