If reading this by email, please tap the title at the top to open your browser for the best experience. Then, clicking individual pictures will reveal higher resolution images.

To my mind, some of the most beautiful work in the area of graphic art was created by the British artist and craftsman, Eric Gill. The intractable problem posed by Eric Gill is not a legacy of his artistic output, but of his personal life. Largely unknown to those outside his family until about 50 years after his death, Eric Gill – by admission in his own unpublished writings – had engaged in personal behavior of a kind that most people would find not only abhorrent but, increasingly, as also criminal.

This is related to the larger problem posed by the work of artists, musicians, and architects whose work is seen as having been collaborative with tyrannical regimes (eg., the Third Reich, the Soviet Union). How do we view beauty in art that either depicts or is simply associated in some way with sin or with evil? (This is a matter I have previously tried to understand in relation to Picasso’s great painting, Guernica.)

To cite Scripture to the effect that “all have sinned,” may help us begin to locate the terrain upon which we need to address the problems stemming from Eric Gill’s biography, but it is not in any way to excuse his conduct. Though all sin is bad, and equally problematic in the eyes of God, not all sin is equal in its damaging effect upon others, and upon ourselves. The traditional distinction in moral theology between mortal and venial sins provides one way to try to parse some of these differences, while not excusing any forms or examples of sin, whether in ourselves or among others.

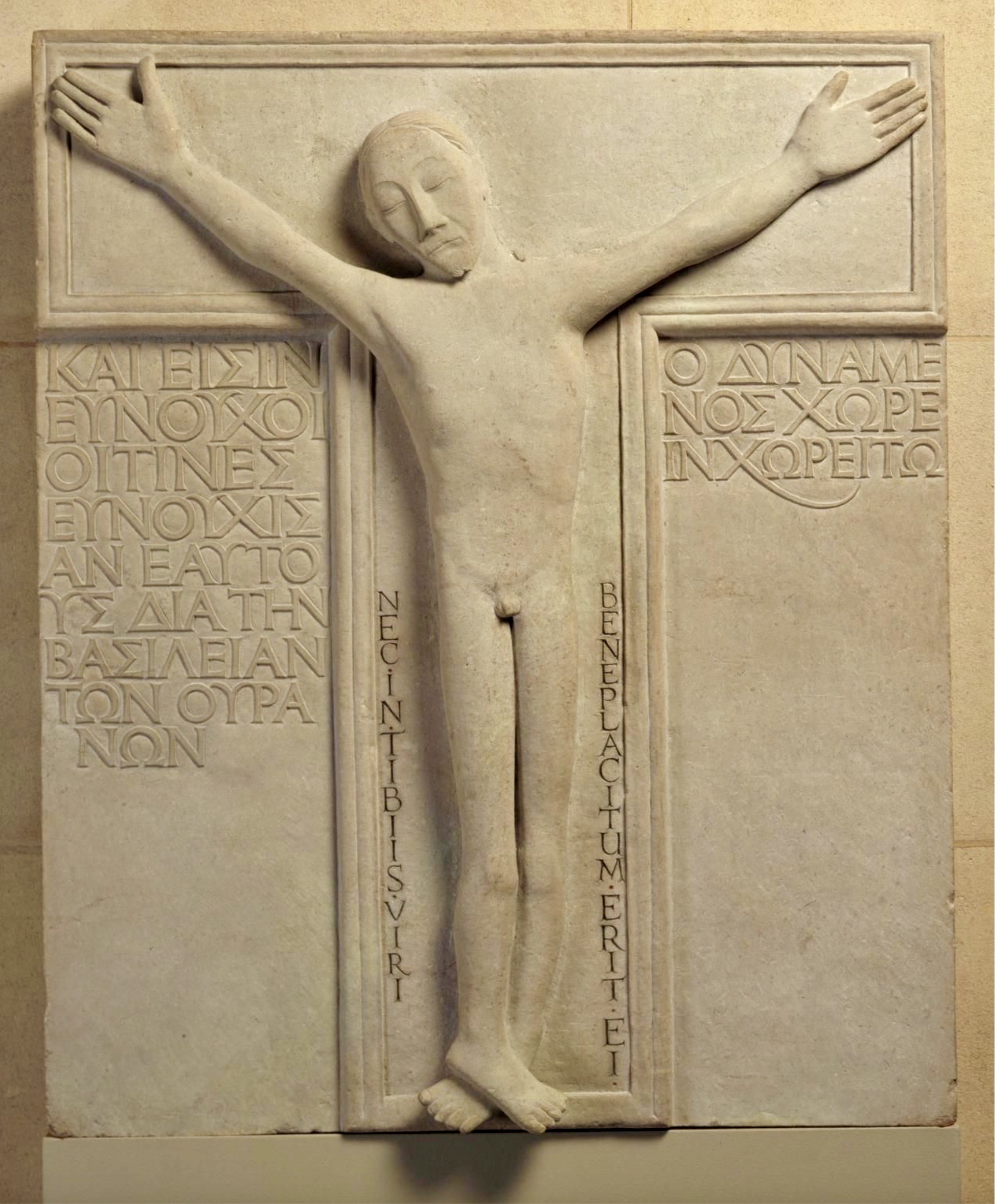

My purpose here is to invite reflection upon how we might appreciate Eric Gill’s religious art, as many did for several generations, without having our view of the merit of his work diminished by our moral evaluation of troubling ethical choices he made, and the lapses from good moral judgment they represent. In other words, and as an amateur student of the arts while also being a retired parish priest and former professor of moral theology, I wish to present some examples of Eric Gill’s art, letting his work speak for itself apart from ethical consideration of his personal life, and without ignoring the problems associated with the latter.

Perhaps my theme here can be summed up in this way: I invite you to benefit from the beauty of what Eric Gill created without asking you to overlook what we have learned about his private life. And I offer this invitation aware that some will not find it possible to accept.

As we consider some of his art, we should not overlook Eric Gill’s impact, at least indirectly, upon much of the daily life of the population of Great Britain (and elsewhere), in the form of three type faces he created. The most well-known is Gill Sans, named after its designer, and evident at almost every Tube stop in London. An effort to erase his work from the public eye, and replace it with alternatives, would require removing virtually every train station sign in Britain. It could be done. Should it?

To put the problem I have raised here most bluntly, how can we appreciate the beauty in the holy art created by someone who behaved in a way most people would describe as sinful? I do not have a ready answer to this question. Note that, in what I have written above about Gill’s behavior, I have not gone into detail. Would that make a difference? If so, in what way?

And even if we refuse to give any amount of attention to Eric Gill’s artwork, we must still grapple with a timeless question: are there any unforgivable sins? Is anyone, because of his or her behavior, beyond the power of God’s redeeming love? Is it not likely that someone having Gill’s religious inclination also possesses a glimmer of moral awareness such that he or she might be open to repentance when – at the end of life – the person faces the awesome and undiminished light of God’s truth-seeking love?

Here is one thing that we can do: pray for the repose of the soul of Eric Gill, and for God’s Providential mercy.

In beginning to approach the questions I have raised here, I would start with some of the distinctions I shared above. I do not think we can deny this reality – that we, as people who are created in the image and likeness of God, and who have lost that likeness through the Fall and human sin, still bear God’s image however marred it may be by the corruption resulting from our sins. And, that we are still capable while in this life of acts and works of uplifting beauty.