This week, on September 9, we observed a significant date on our personal calendar by celebrating the birthday of one of our sons. September 9 was already a notable date for us beginning some years before his birth, after our move to Memphis in the summer of 1983. During those years, the date became associated with an addition to the Episcopal Church Calendar that has readings appointed for it in our Lectionary. September 9 is designated as the feast of The Martyrs of Memphis: Constance, Thecla, Ruth, Frances, Charles Parsons, and Louis Schuyler.

To those unfamiliar with its history, the official title for this feast day may suggest dramatic images of early Christian saints contending with ferocious animals and or human adversaries in the name of the Faith. Which then raises questions about whether, perhaps, the Memphis in question was the one in ancient Egypt. Yet, the name designation for this day can be instructive for all of us because it may remind us of something we once learned – that the etymological root of the word martyr lies in the ancient Greek word meaning ‘witness.’ Hence, those persons we commemorate on the Church’s Calendar because of their examples of Faith are remembered for being especially compelling witnesses to God’s redemptive mission in Christ, regardless of whether they faced circumstances that might have led to a heroic death.

The Martyrs of Memphis provides an occasion for us to remember the men and women who remained in Memphis to minister to those with whom they faced together the ravages of a severe Yellow Fever epidemic, from which they could have fled to safer places elsewhere. Unknown to them was the fact that this horrible plague was a mosquito-borne infectious virus, and not something arising from ‘swamp vapors’ or bad city air. Among the faithful persons who succumbed to the fever, and who are remembered on the feast day of September 9, are the four women named in the feast’s title who were community members of the Sisters of St. Mary, Father Charles Parsons, the last remaining Episcopal priest in the city, and Father Louis Schuyler, who came as a volunteer from New Jersey to take Parsons’ place and join the Sisters in ministry.

Words from the collect (or principal prayer) for the feast day of the Martyrs of Memphis capture well why these particular individuals are named among so many others – known and unknown – who shared their faith as well as fate: “We give you thanks and praise, O God of compassion, for the heroic witness of the Martyrs of Memphis, who, in a time of plague and pestilence, were steadfast in their care for the sick and dying, and loved not their own lives, even unto death…”

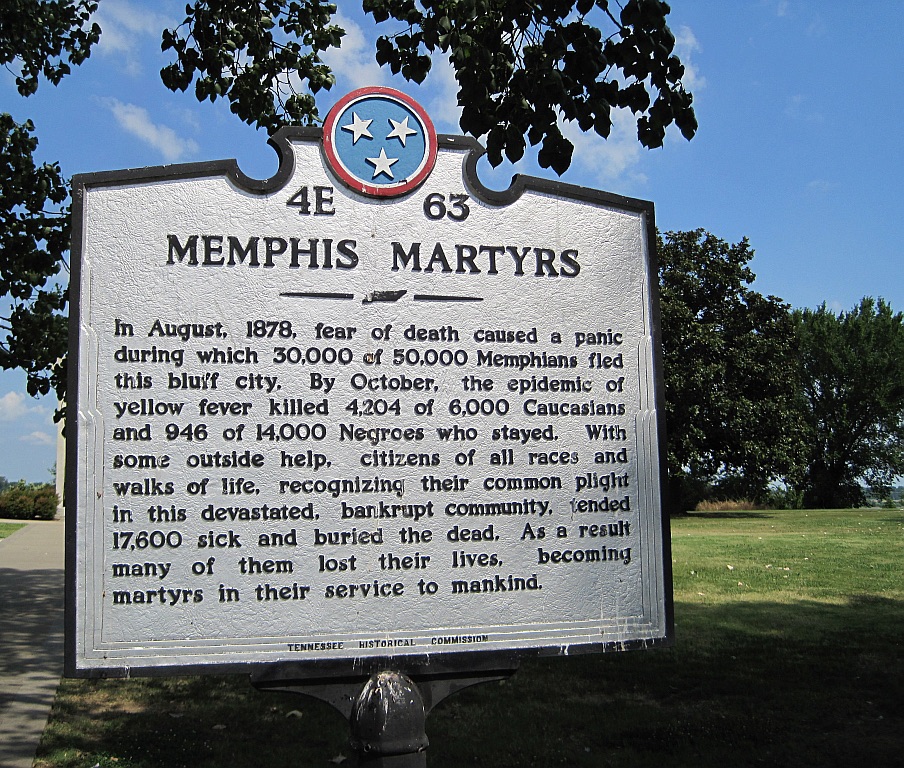

The generic character of the title for this significant feast day was chosen to help us also remember that the number of those who died in the epidemic, not only in Memphis, but up and down the Mississippi River and beyond, numbered in the thousands. Memphis’s historic Elmwood Cemetery, its oldest, has a particularly moving monument that complements the contemporary riverside sculptural composition by Harris Sorrelle (displayed above). At Elmwood, instead of having an impact upon the use of anonymous and aptly dark-colored figurative silhouettes, as Sorrelle’s sculpture does, the cemetery monument provides just paragraphs of words, stating in plain but moving terms the reality that lies below where cemetery visitors walk (as the following image attests). As the Elmwood monument notes, at least 1,400 Yellow Fever victims are buried in nearby unmarked mass graves.

The faithful witness of those who died ministering to and with others among the Yellow Fever victims in Memphis in the 1870’s can have the effect of prompting us to reflect on the very different circumstances in which we live, with our advances in medicine, healthcare, and social services. Nevertheless, the COVID crisis of 2020, and its lingering legacy, can also remind us of our mortality, our higher calling to seek godly life in its fulness, and to be faithful companions with and to those less fortunate than ourselves.

Additional note: a tragic-comic aspect of the Yellow Fever’s impact upon Memphis was another pre-scientific belief (in addition to the ‘swamp vapors’ theory regarding its origin) amongst those who remained in the city. It is said that those who seemed to have the lowest mortality rate were corpulent men who smoked cigars, the smoke from which may have warded off the mosquitos responsible for the plague’s transmission.