When we as Christians pray, we don’t simply pray to God. With faithful assurance, we pray with and through God! As Paul tells us, “When we cry, ‘Abba! Father!’ it is that very Spirit bearing witness with our spirit…” This is because, when we pray “to the Father,” we also pray with and through the Son. We are enabled to pray with and through the Son following our Baptism. For after Baptism, we are assured that we pray in the Holy Spirit. We therefore pray to God not ‘from the outside,’ but ‘from the inside’ of God’s own being and nature!

Well, how can this be? As we can easily discover, every Eucharistic Prayer in The Book of Common Prayer has a common shape. For all of our Eucharistic Prayers are prayed to the Father, through the Son, in the Holy Spirit. This is not an accident. Jesus modeled this in his own life, and particularly at the Last Supper.

When we repeat Jesus’ pattern, offered at that supper, we stand with him around the same table. And by his graceful invitation, we join his prayer to the One he called, ‘Our Father.’ Our prayer with him, to the Father, is in the power of the Spirit, the same Spirit he spoke about at that table. He modeled at that supper what grace means in practice.

Through the grace of the Holy Spirit, Jesus shares with us his own particular intimacy with the Father. Inviting us to stand with him as he prays, he offers the whole world back to the Father-Creator. By this, Jesus – and us with him – fulfills the divinely intended-but-failed stewardship vocation of the mythical Adam and Eve. And so, this is also our vocation, to offer up to our Father all that truly belongs to the Creator. Sharing with Jesus the grace of the Holy Spirit allows us to join him, the Son, in his ongoing Eucharistic vocation.

A good way we can live into the saving implications of God’s Trinitarian nature, is to engage in some creative imagining. Imagine that, in this moment, Jesus reaches out his hands to us. In reaching out his hands, he does not simply extend his greeting. Extending his embrace, he invites us to join him by standing with him, closely at his side. By his invitation, and our acceptance of it, he shares with us his own intimate and particular relationship with our Father.

And with this invitation, he gives us the power of the Spirit, making it a reality in our lives. Because the invitation comes from him, the power of the Spirit he shares with us is God’s grace-filled power. Jesus makes all this actual and true, whether we feel it or not.

This Trinitarian shape of prayer is different from how we usually imagine prayer. Commonly, we think of prayer as our communication to God. When we feel aware of God and close to God, we speak to God of what is good and well and of that for which we feel thankful. And we often ask for help. But, when there seems to be a veil between us and God, we speak to God with lament or we complain, sometimes in anger. This concept and experience of prayer is ‘subjective,’ and therefore narrow. That is, it is a concept of prayer based primarily upon our personal, interior, experience. It reflects our experience of being the subjects of perception and action. Yet, as the Prayer Book Catechism teaches us, prayer is first of all responding to God.

As we learn from Jesus, and by the Holy Spirit, true prayer is not something we do, which we somehow manage to achieve through our faithfulness, devotion, or energy. True prayer is something we allow God to do within us. True prayer is the kind of praying that we find God already making real within us through the indwelling Grace of the Holy Spirit. The Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit are constantly engaged with one another, in what the Eastern Christian tradition calls ‘a dance,’ a perichoresis. Prayer involves being drawn into this dance. Prayer is sharing in the Trinitarian relational being of God. Prayer is participation in the community of fellowship that exists within God’s own being.

The Trinitarian pattern of our lives rests upon the Trinitarian shape of our prayers. We can accept Jesus’ invitation to stand with him. We then experience his own fellowship with the Father, in the grace-filled power of the Holy Spirit. This enables us to live truly. To live truly, is to live to the Father. It is to live with and through the Son. And true prayer is to live in the power of the Holy Spirit.

And so, we seek to live in the way that we pray: to the Father, with and through the Son, in the Holy Spirit.

Note: This post is based on the Western Church’s observance of Trinity Sunday, on June 15, 2025. My title is based on a well-known metaphor found in John’s Gospel. The text here is based on my homily for that occasion, which may be accessed by clicking here.

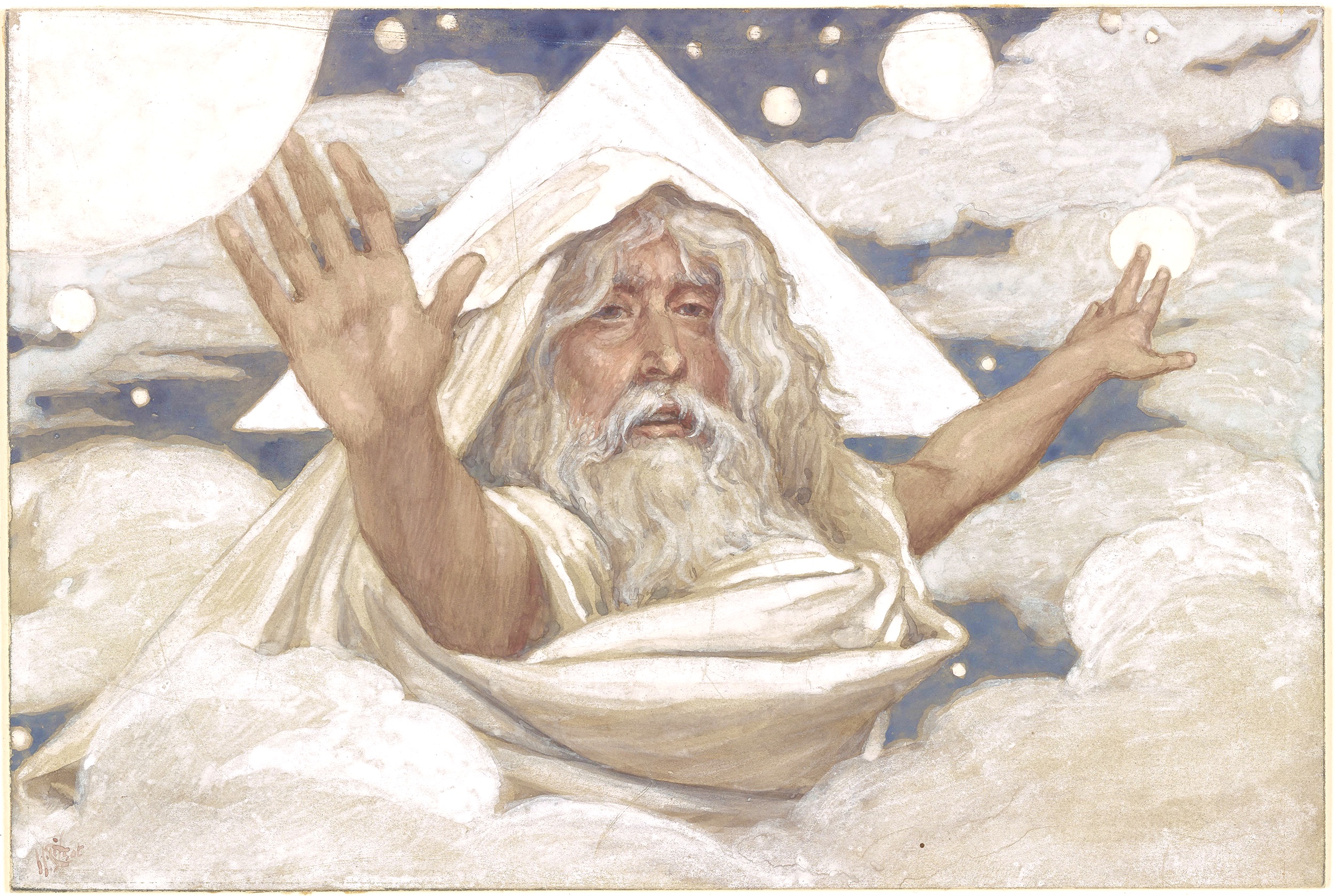

My goal is to commend the assurance of hope that lies within the Gospel. And while being aware of concerns about the so-called ’scandal of particularity’ associated with Christianity and Judaism, we should be aware that God is free to offer a similarly positive spiritual experience to those of other religious traditions, or of no particular tradition with which they may identify. I hope to address Hunt’s evocative painting, featured above, in a subsequent post.