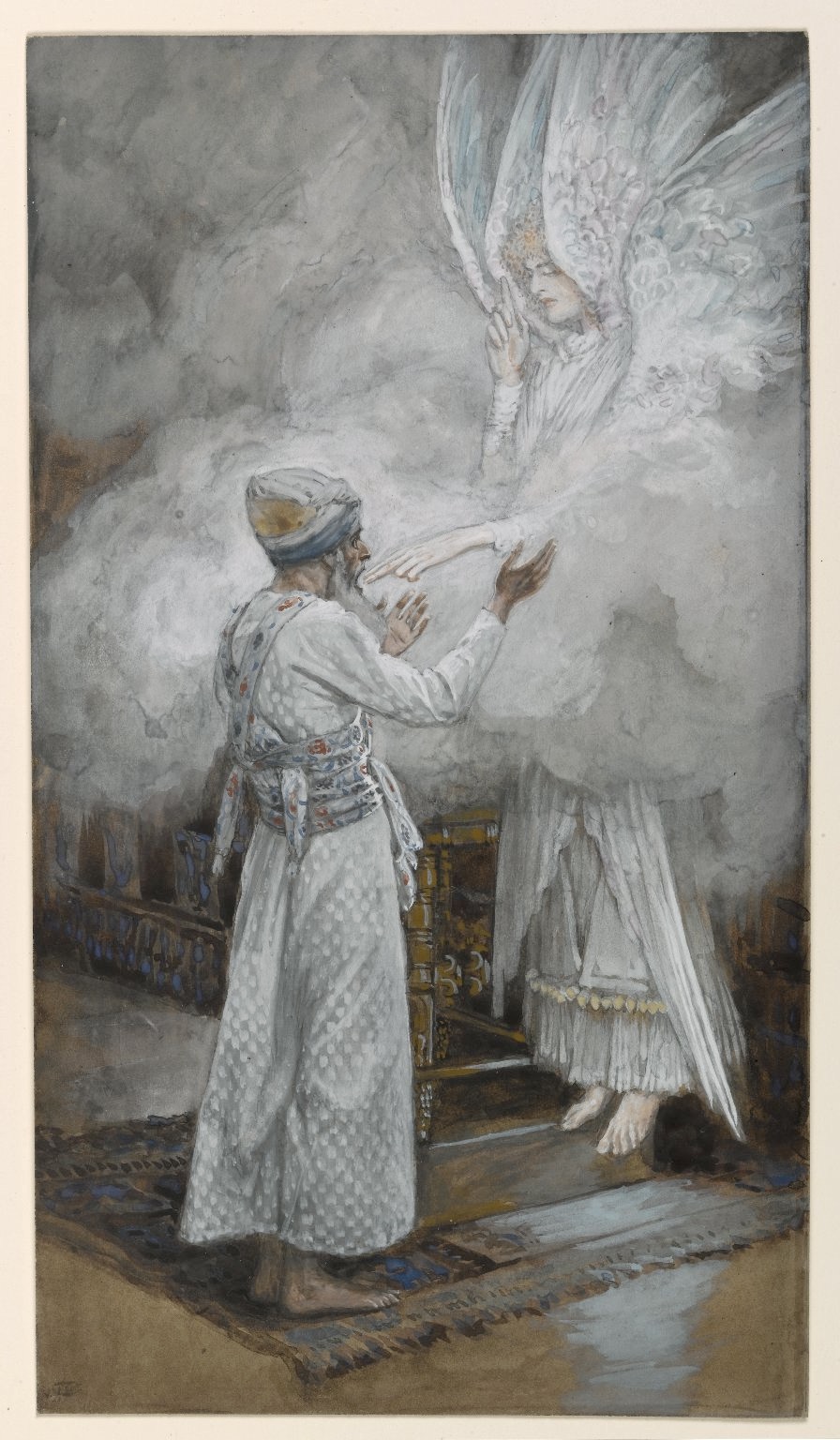

Picture the scene: About 750 years before Jesus, at the Lord’s bidding the prophet Isaiah goes out to the south side of Jerusalem near the aquaduct. He has been asked to do a difficult thing, to meet the fearful and apprehensive Ahaz, king of Judah. This happens at the moment when God’s people are threatened by Tiglath-pileser, king of the Assyrians. Making a bad situation worse, the Assyrians have been joined by armed forces from the separated northern kingdom of Israel, who have already been brought under subjection by the threatening foreign power. Ahaz does not respond as God would like. When he demurs from asking God for a sign of assurance, Isaiah confronts him with the Lord’s Word:

“… Listen to this, government of David! It’s bad enough that you make people tired with your pious, timid hypocrisies, but now you’re making God tired. So the Master is going to give you a sign anyway. Watch for this: A girl who is presently a virgin will get pregnant. She’ll bear a son and name him Immanuel (God-With-Us). By the time the child is twelve years old, able to make moral decisions, the threat of war will be over. Relax, those two kings that have you so worried will be out of the picture. But also be warned: God will bring on you and your people and your government a judgment worse than anything since the time the kingdom split, when Ephraim (northern Israel) left Judah. The king of Assyria is coming!”

What a strange promise! How could the promised birth of a child be a gift for a troubled world?

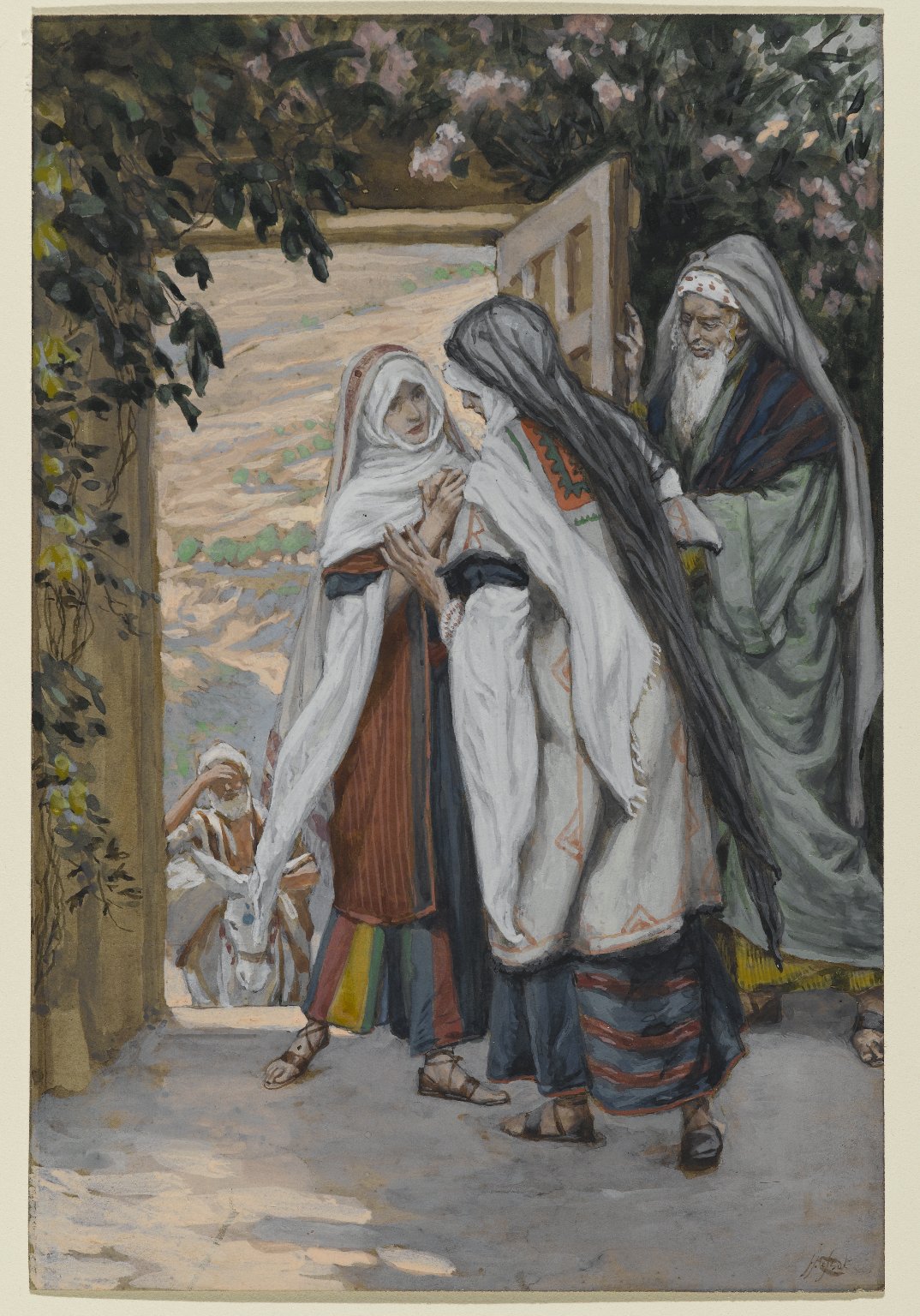

This is the kind of promise that Mary later received through the Angel Gabriel. We all receive a similar promise when we are called to acknowledge and accept that same Gift-Child that Mary received.

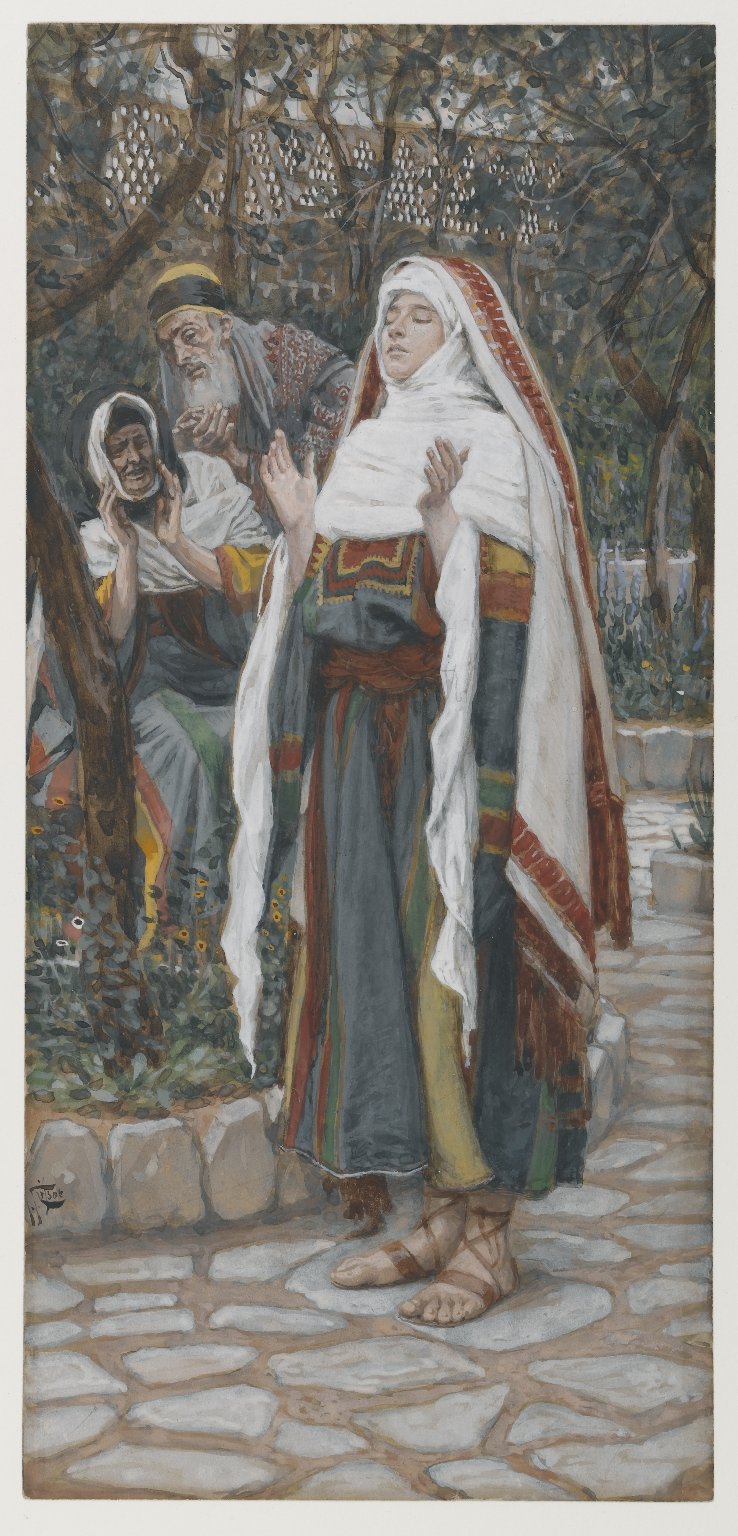

During Advent this year we have reflected on how there can be several aspects of our response to God’s call, and to the promises latent within God’s Gift to us. Fear is often our first reaction, followed then by wonder and uncertainty about the fit between God’s promise and our own suitability for receiving it. By attentiveness to God’s Grace, our uncertainty can be transformed into a humility ~ a humility that is willing to accept the Word of Promise and the Call to receive it. And if we come that far, if we are willing to believe and remain attentive, we may experience a wonderful moment. We find it in a fourth aspect of Mary’s response to God’s Word of Call. It is quite simply, Joy! There is no other word for it. Both Mary and Joseph, each in their own way, accept God’s unlikely and unexpected Word of promise. By accepting and receiving God’s will for what it is, they find a beautiful joy.

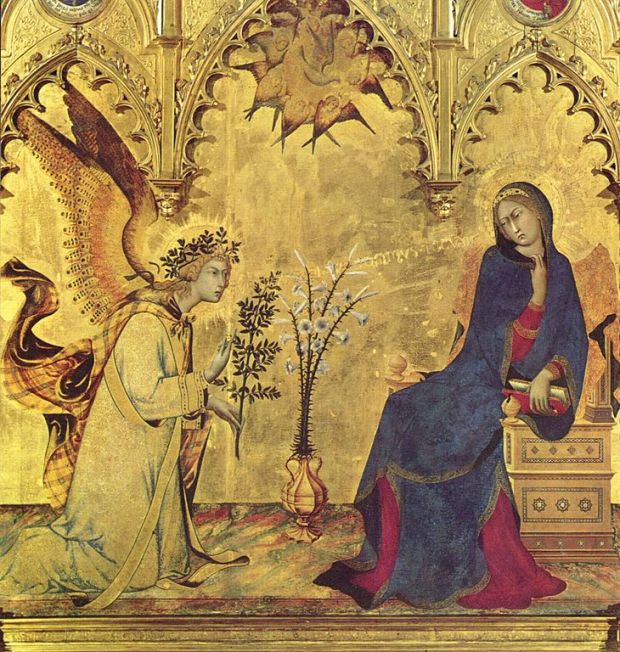

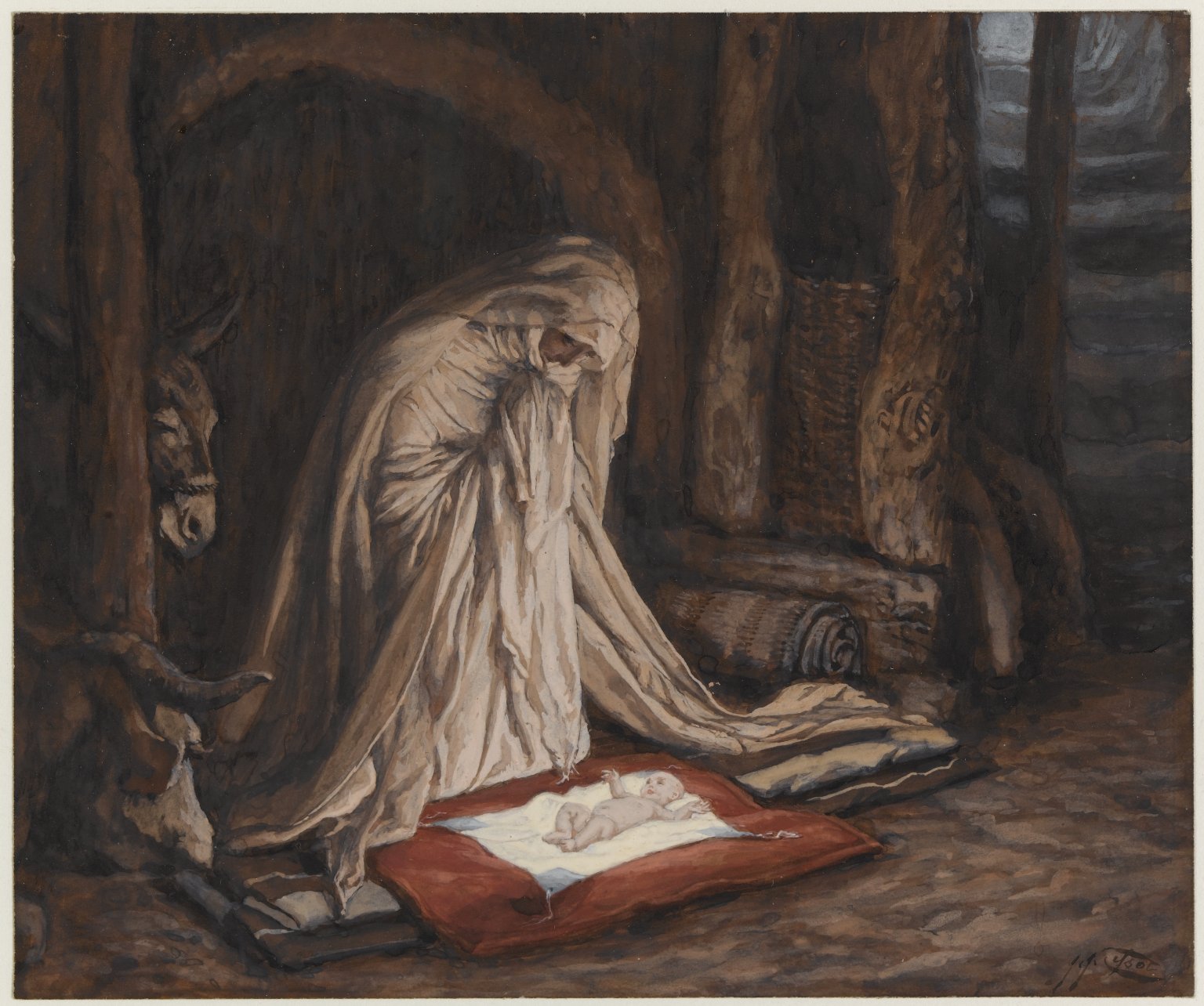

Over the course of Advent, I shared with you three images portraying aspects of the Angel Gabriel’s Annunciation to Mary of the promised gift of a child ~ a child who would be God with us. In the image above, El Greco beautifully captures the sublime quality of the moment. Having accepted God’s Word in humility, Mary’s eyes and her whole being are uplifted to receive the message. Her up-turned hand says it all! The gilded and hovering angel points upward, in the direction where all this is supposed to go, into the realm of Spirit. This is where the Lord will ascend through his Resurrection, taking us and our humanity with him into the very being of God.

Joy may not be the defining feature of our lives today. Yet, we can find the fullness of joy in the beautiful Gift we celebrate this week. For we receive a gift whose meaning and value we can never fully anticipate in advance.

To this gift, Mary says “Yes!” And, with her, we can say, “yes,” as well. Yes to God’s Word that comes to us as both promise and call – a promise that he will be with us always, as we accept him for who He really is. And, a call for us to become new persons in him. For in him we find a spiritual maturity that this world can never give.

In raising our hearts in assent to God’s promises, and by receiving God’s call to be transformed by the Spirit, we grow. We grow into that quiet joy which was Mary’s, instilled by the Angel’s visit. Behold – a virgin has conceived, and has borne a Son, and we call his name Immanuel – for God is with us!

The image above is of El Greco’s Annunciation (1600). The biblical quotes from Isaiah are based on Eugene Peterson’s translation, The Message. This post is based on my homily for the Fourth Sunday of Advent, December 22, 2019, which can be accessed by clicking here.