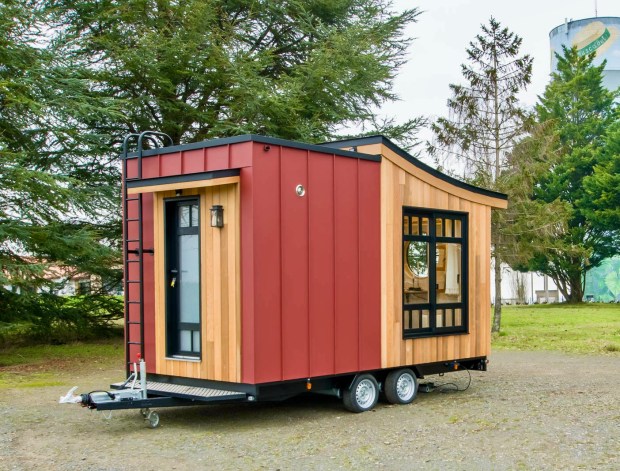

As earlier posts of mine attest, I have been interested for some time in the Tiny House movement, which has now become a widespread phenomenon. Whole Tiny House communities are being developed, and Tiny House construction designs have been proposed as an alternative approach to addressing homelessness. Reflecting on this movement, and the broad appeal examples of Tiny Houses seem to have, I have given some thought to what this development in small scale architecture may represent, and to what it may tell us about how we want to live.

I can see an impulse similar to the pursuit and enjoyment of living in a Tiny House in some attractive parallels, which also represent a quest for discerning a simpler way to live. Quite aside from a specific focus on contemporary examples of Tiny Houses, many people appear to have an interest in reading books like Thoreau’s Walden, or those by John Muir. I continue to meet folks who like the idea of having a small boat in which one can actually ’cruise,’ even on local lakes. And still others seem to share my fascination with living environments inspired by Japanese aesthetics.

If these musings seem familiar, learning more about the Tiny House movement is worth pursuing. Here are some observations I have made in the course of my own reflections on the current popularity of this movement:

First, the appeal of Tiny Houses has much to do with the process of rediscovering, and learning more about the beauty of living simply. And therefore, about more than managing to accept being without some things, but actually doing well with less. Marie Kondo’s videos and published writing have attracted a good deal of attention regarding the desirability of organizing our household belongings, and paring down what we have toward living with what we truly love.

Viewing and reflecting on examples of Tiny Houses can aid one’s discernment regarding needs vs wants. Most of us have probably considered this distinction from time to time, and have likely also experienced some frustration with our halting efforts to enact our reflection upon it. We know we have wants, which often masquerade as needs, while we may not sufficiently consider the potential value to us of having wants that are correlated with our needs. After all, a premise of this post rests on a paradox: the assumption that I not only want to live more simply, but that I may also need to!

Here, briefly noted, are some potential benefits that may come from spending time in a Tiny House:

- Living off the grid becomes a much more realistic goal when choosing to live in a Tiny House. Tiny Houses also allow for mobility in relation to one’s surroundings, even if it is not a frequently exercised opportunity. Changes in one’s locale can lead to learning opportunities.

- Those who build their own or who choose to do maintenance work on a Tiny House are more likely to learn how to use, and use more ably, simple and hand-powered tools.

- Tiny Houses are well suited as places in which we can experience solitude as a positive aspect of our lives, while also providing an excellent context for significant times spent with others.

- Living or spending time in a Tiny House may allow us to have increased time for personal reflection, and an opportunity further to discern our vocation, in addition to our more usual absorption with occupational concerns.

- Tiny Houses therefore have the potential to be places in which we read more, and spend less time consuming social media or watching videos. While every living place for which we have some care requires time and attention, the theory behind choosing a Tiny House as a place to live assumes that we can devote more time to actually living, rather than preparing to live. Reading makes the world bigger and our lives richer.

For much of the above, and as a both–and rather than an either/or starting point, I commend considering adding a form of a ‘Tiny House’ to your present circumstances rather than making a radical change from them. Experimenting with what can be done with less, while also still retaining one’s present home, can be instructive. This can be accomplished by, for example, purchasing a used but well-equipped small RV. We have recently seen some interesting examples on the road, and ones that could fit in a standard home garage.

For us, it has been our 1988 24 ft trailerable sailboat that has provided this kind of learning opportunity. With its relatively small cabin (about half the length of the boat), comfortable berths (or bunks), a camping stove, cooler, portable toilet, and cockpit which serves as a small ‘back porch,’ we can meet most of our daily needs for a week or more at a time. The slip for our boat is under $200/ month, including electricity and water connections, if needed (ie, if the boat is not yet off-the-grid-ready, though our boat is now thus equipped). DAYSTAR has become our floating ‘tiny house’ or ‘cottage.’

Ably and effectively inhabiting this principle of beautiful simplicity is turning out to be a lifelong project for me, and I believe this is also true for others. I am a neophyte in the process. Perhaps my readers have some similar experience with this ongoing process!