Labor Day is around the corner and some of us may receive and enjoy a day off from work. What we call retirement, a stage in life I am presently enjoying, tends to represent leaving work behind. Yet these and related ideas rest upon a common assumption, that work is different from, and in some ways inimical to, enjoying fulfillment in life.

I find a biblically based theological insight helpful when thinking about work. As with many matters that can be looked at from the perspective of Christian moral theology, our view of work can be enhanced by making reference to four specific reference points. These are, first, what we have learned about God’s purposes in Creation for this or that aspect of our lives; then, what impact sin associated with our Fall has had upon what we are thinking about; third, how God’s ongoing work of Redemption has restored and or transformed the matter presently under consideration; and fourth, to ask what future – if any – does this aspect of our lives have in Christ.

Work provides a wonderful topic for engaging in this fourfold inquiry. Based on our common way of thinking about work, it may be hard for us to consider the meaning of work from any other vantage point than of attributing its role in our lives to the Fall and to the ongoing effects of human sin. Yet, we can also learn from many who have come before us who have distinguished work from toil. This can help us see how forms of labor, and pejorative associations the word may have for us, are surely due to our proclivity to link such activity with burdensome unpleasant duties.

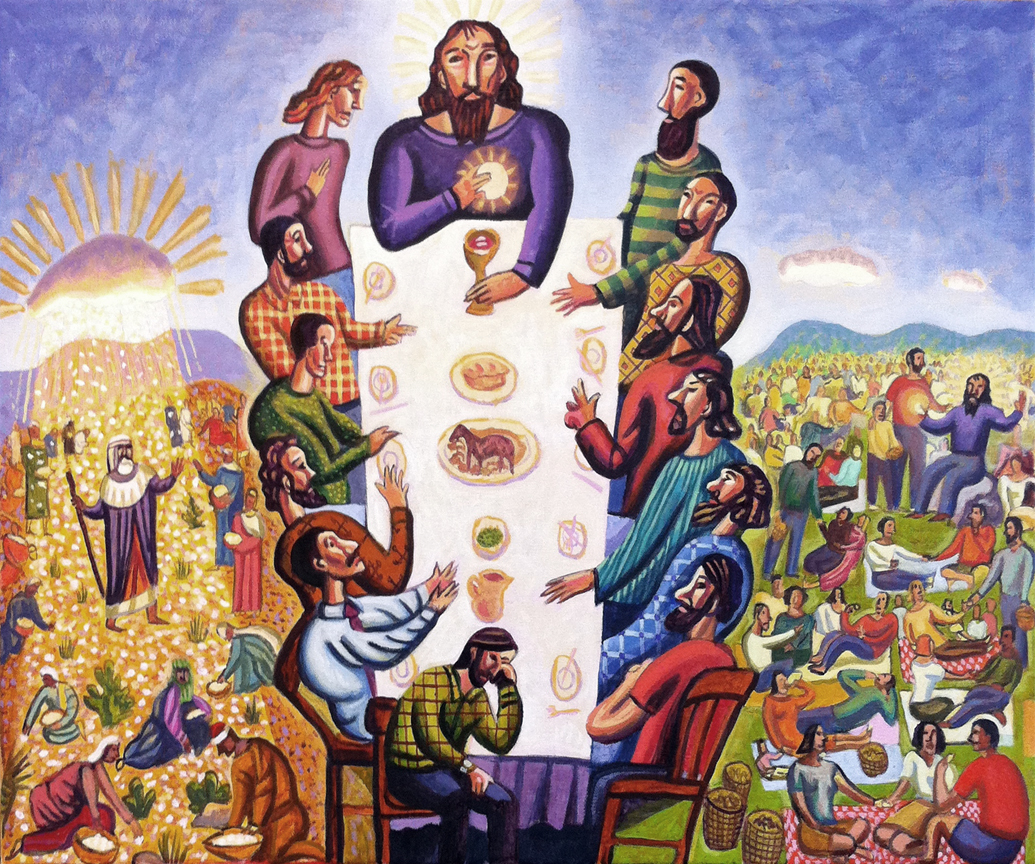

For what we may overlook is the biblical view of how God has shared stewardship responsibility for aspects of Creation with us, as beings created in God’s image and likeness. This was symbolized by the way that our mythic forebears (Adam and Eve) were given their ‘work’ of naming the animals as a path toward fulfillment. It was not until their expulsion from the Garden that the first human beings are described as prone to acts characteristic of sin. Thereupon, in biblical theology, our heavenly ‘work’ of praise, and of divinely-invited participation in God’s Creation stewardship, ceased to be pleasingly ready pathways toward human fulfillment, and became energy draining and spirit-diminishing activities – such as we tend to find them to be now.

A growing segment of the wider Christian community shows signs of acknowledging how God’s work of Redemption is ongoing, quite aside from its ‘once and for all time’ episodic saving events. The pattern and purpose remains the same – nothing fundamentally new is added, nothing old of lasting value taken away. Preeminent remains God’s abiding purpose for us to become and be God-like in God-intended ways. For, as Athanasius taught us, the Son of God became the Son of Man, so that the children of men and women could become the children of God. Work – not toil nor burdensome labor but creative and fulfilling work – remains a vital part of our holy path toward wholeness.

And to remind us of this abiding truth, the loving Creator has spread around us an uncountable abundance. These are the signs of outpoured and participatory grace, some of them very small, like stepped-upon seashore pebbles and tiny blossoms among hurried-by roadside weeds.

Too quickly we dismiss the significance of our our small acts of selfless giving, not to be counted by us, but adding up to so much more than we imagine in the life-growth of others. This is our holy ‘work,’ overlooked but important stepping stones on our path toward living into the godly fullness with which Christ fills us.

If on our daily course our mind

Be set, to hallow all we find,

New treasures still, of countless price,

God will provide for sacrifice.

Old friends, old scenes, will lovelier be,

As more of heaven in each we see:

Some softening gleam of love and prayer

Shall dawn on every cross and care.

[John Keble, “Morning,” from The Christian Year]