If reading this by email, please tap the title at the top to open your browser for the best experience. Then, clicking individual pictures will reveal higher resolution images.

Hagia Sophia (late 19th century photo), showing a later-added (and no-longer-extant) marble paneled exterior

The first great church in Christendom, and the largest for a thousand years, was the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul. Many people think of this building as a mosque, the role in which it served from the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453 until it became a museum in 1935. The addition of minarets reinforces this historic identification of the building with Islam, and those tower-like structures once again serve (since 2020) as a means to broadcast the daily multiple summons to Muslims to attend the designated times of prayer.

This stunning building’s historical association with two of the worlds most prominent monotheistic religions has given rise to a paradox. The architectural form many of us readily associate with Islamic mosques, epitomized by present-day Hagia Sophia, is a form derived from a Christian house of worship. Most mosques, including those recently built around the world, have a structure reminiscent of this building, constructed under the reign of Justinian as the principal Christian cathedral of the late Roman or Byzantie empire, between 532 and 537 A.D.

Hagia Sophia as it sits today in modern Istanbul

The earliest Christian gathering places, before Christianity was officially recognized in the Roman Empire, were often in synagogues or in private homes as well as in safe outdoor places. Once Christians could build and maintain churches without interference, a common stylistic choice was to adopt the Roman basilica style of building, long used in Roman cities as locations for offices, courts, and for other public and business functions. They were usually designed with a rectagular floor plan, containing a central nave, accompanied by side aisles that were separated by columns supporting the central ceiling and roof.

Roof coverings over the side aisles were built at a lower height, allowing for clerestory windows in the nave above them, illuminating the central area. At one end was an apse, covered by a half or semi-dome. At the center of the apse was a dais where in Roman buildings magistrates sat, and which in later churches provided seating for the clergy.

Longitudinal plan for the Basilica of Maxentius and Constantine, Rome

Noticing how the above described spatial arrangement continues to be evident in modern churches helps us appreciate the significance of Justinian’s innovative plan for the Hagia Sophia. For the longitudinal Roman-derived spatial arrangement, evident in the basilica plan above, led in the West to the the placement of altars as well as the clergy attending them at one end of the building. Over time, these longitudinal basilica plans influenced Western medieval architects to design Gothic churches and cathedrals based loosely on the Latin cross, where the longitudinal length of the nave replicates the tall upright base of the cross, upholding the horizontal arms.

A common floor plan for Western, Latin, longitudinal church design (entrance at the west end; altar placed in the apse at the east end; nave is shaded)

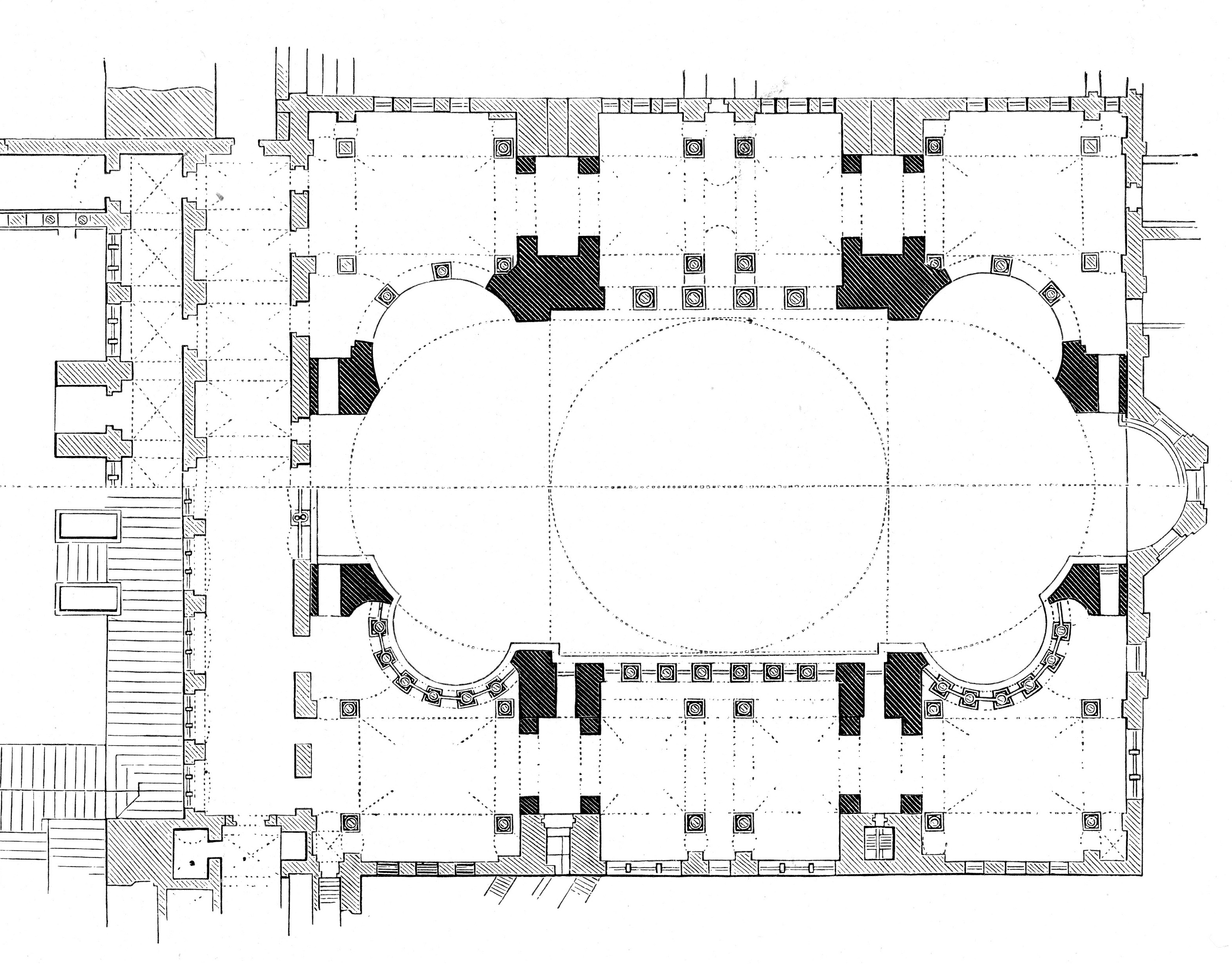

By contrast, Justinian’s Hagia Sophia plan, widely influential in the Christian East, and subsequently adopted in Islamic architecture for mosques, is based on what is commonly called the Greek cross, where each of the four ‘arms’ of the cross are of equal length. Plans based upon the Greek Cross therefore lend themselves a to placement within a square and or a circle, rather than within a rectangle. They also provide scope for the placement of a large dome over the central and main part of the building.

Plan of Hagia Sophia (with an apse, but with a spatial arrangement based upon an equal-armed cross)

The effect of this Greek Cross-based development in church architecture has a symbolic significance in the liturgical use of buildings based upon it. The altar, even if placed near to one end of the building, sits more closely toward the center of the structure and within the resulting worship space. To be sure, the liturgical use of such church buildings in earlier centuries, and the theological views of those who worshipped in them, often implied hierarchical understandings of church membership, something common in the Latin West, as well. [Imagine what was subtly – if not intentionally – communicated when clergy were observed sitting in the places associated in the prior realm with public officials and the exercise of their offices.]

Yet, it is interesting to observe how a preference for Greek Cross (or circular) shaped building plans has received increased attention in modern liturgical renewal. This is because liturgical spaces based on such plans lend themselves more readily to a revived understanding of the Eucharist as an activity of the whole church, and not just of some who are designated if not also elevated to lead it, and provide its benefits.

In a subsequent post I will reflect on some further architectural features of Hagia Sophia and of designs based upon it.