If reading this by email, please tap the title at the top to open your browser for the best experience. Then, clicking individual pictures will reveal higher resolution images.

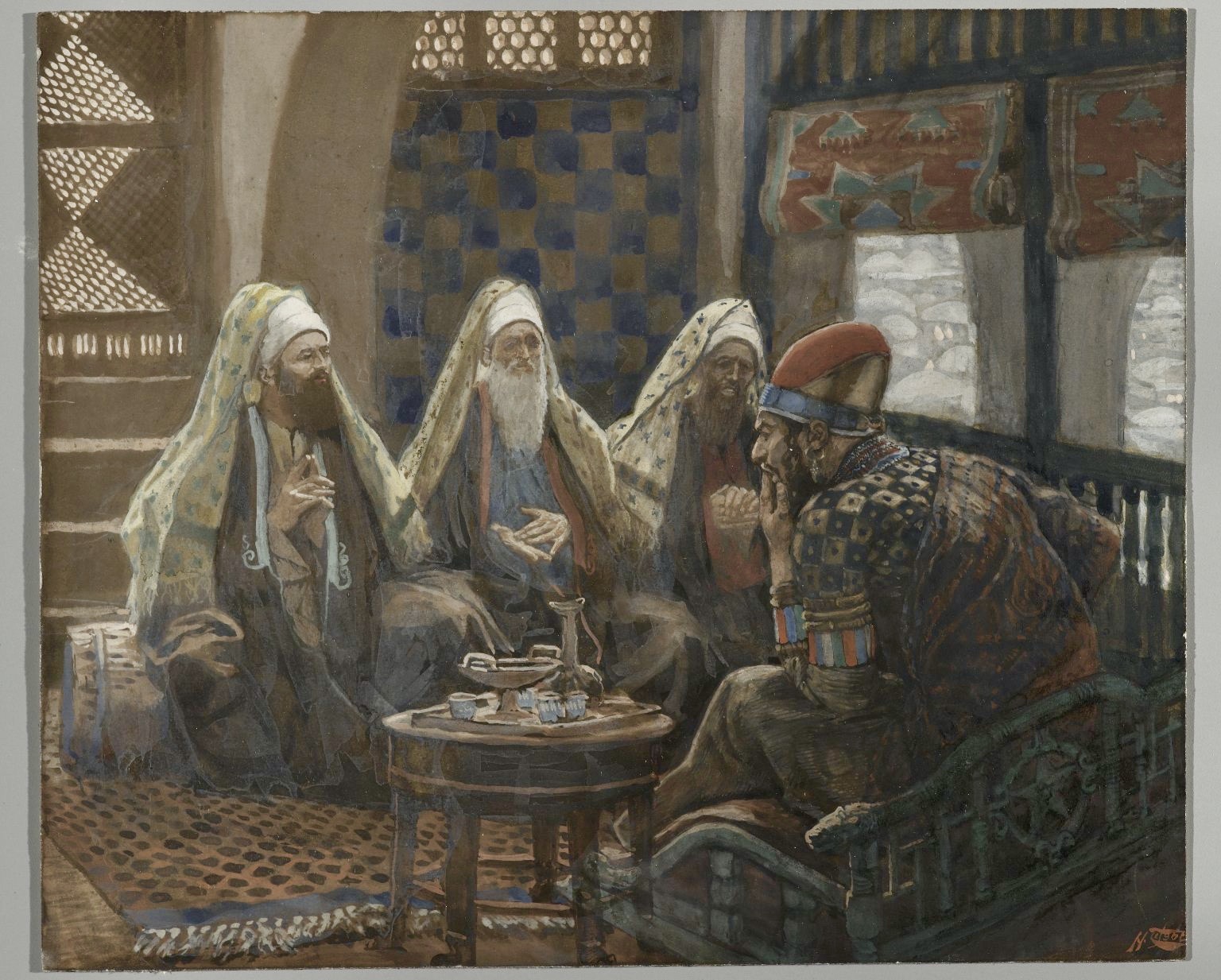

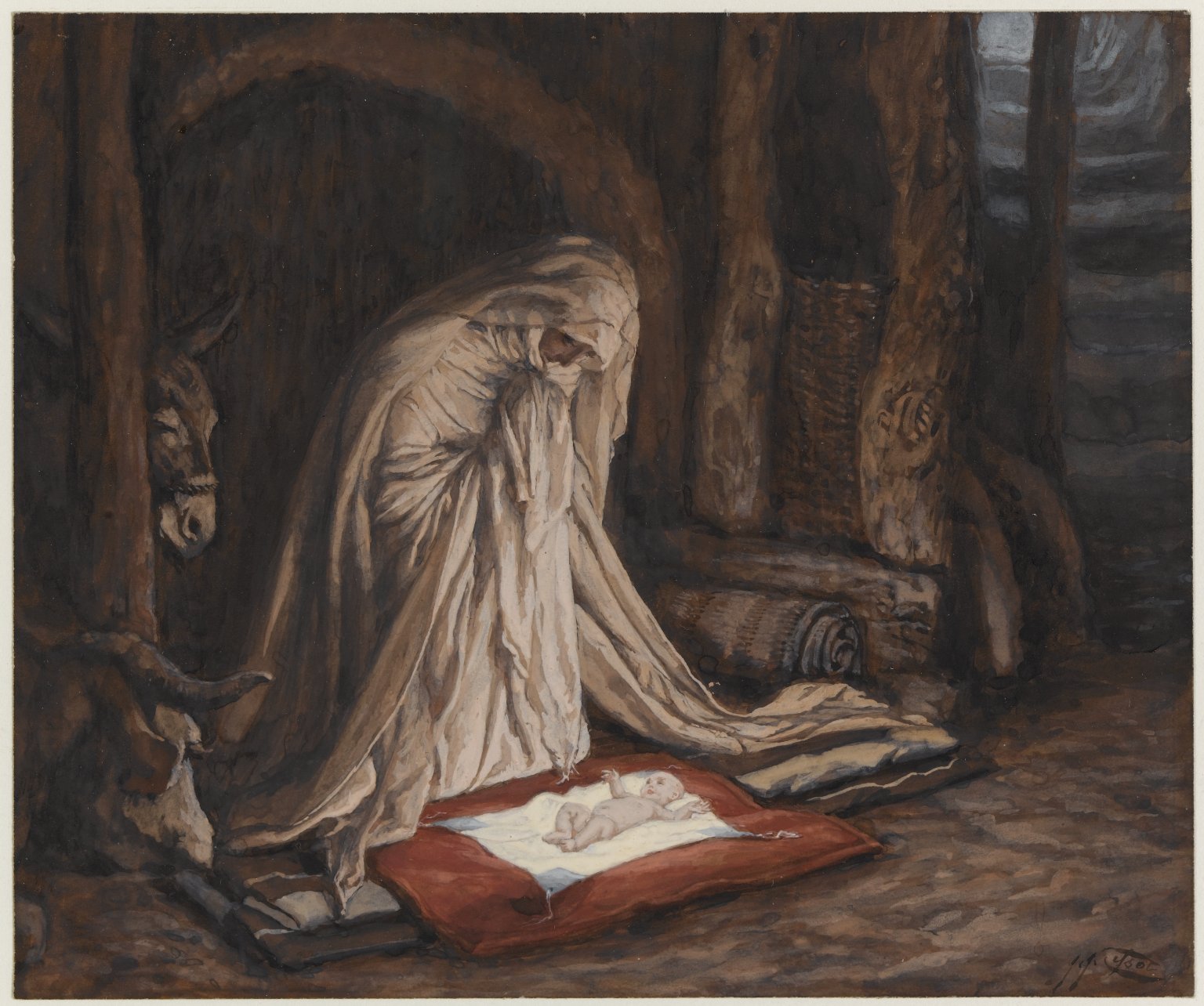

James Tissot, The Pharisee and the Publican

This past week I witnessed a beautiful act of repentance. A new friend shared with several of us that he had done something he clearly regretted. I began to see the shame and grief he was carrying within himself, despite his initial display of upbeat friendliness. I suspect that he had not joined us consciously intending to share details about what he had earlier done. But, after a bit, his sense of accountability to us, as well as his desire to reconnect with us, overcame his reluctance to be candid. His face became dark, and we could see anguish in his facial expression while – embarrassed – he described what had happened. His principal regret, he said, was that he had let himself and his family down, and he was sad that he had let us down, as well.

It was an uncomfortable few minutes, both for him, and for us. But I was struck not only by the pathos of the moment, and of his admission. I was moved by the beauty of his expression of repentance, and especially by his at-first discrete and then winsome smile as he received and responded to our assurances. We told him that he was beginning to make things well by sincerely sharing his recent experience with us.

The moment passed by all too quickly, especially given how profound it had been for several of us.

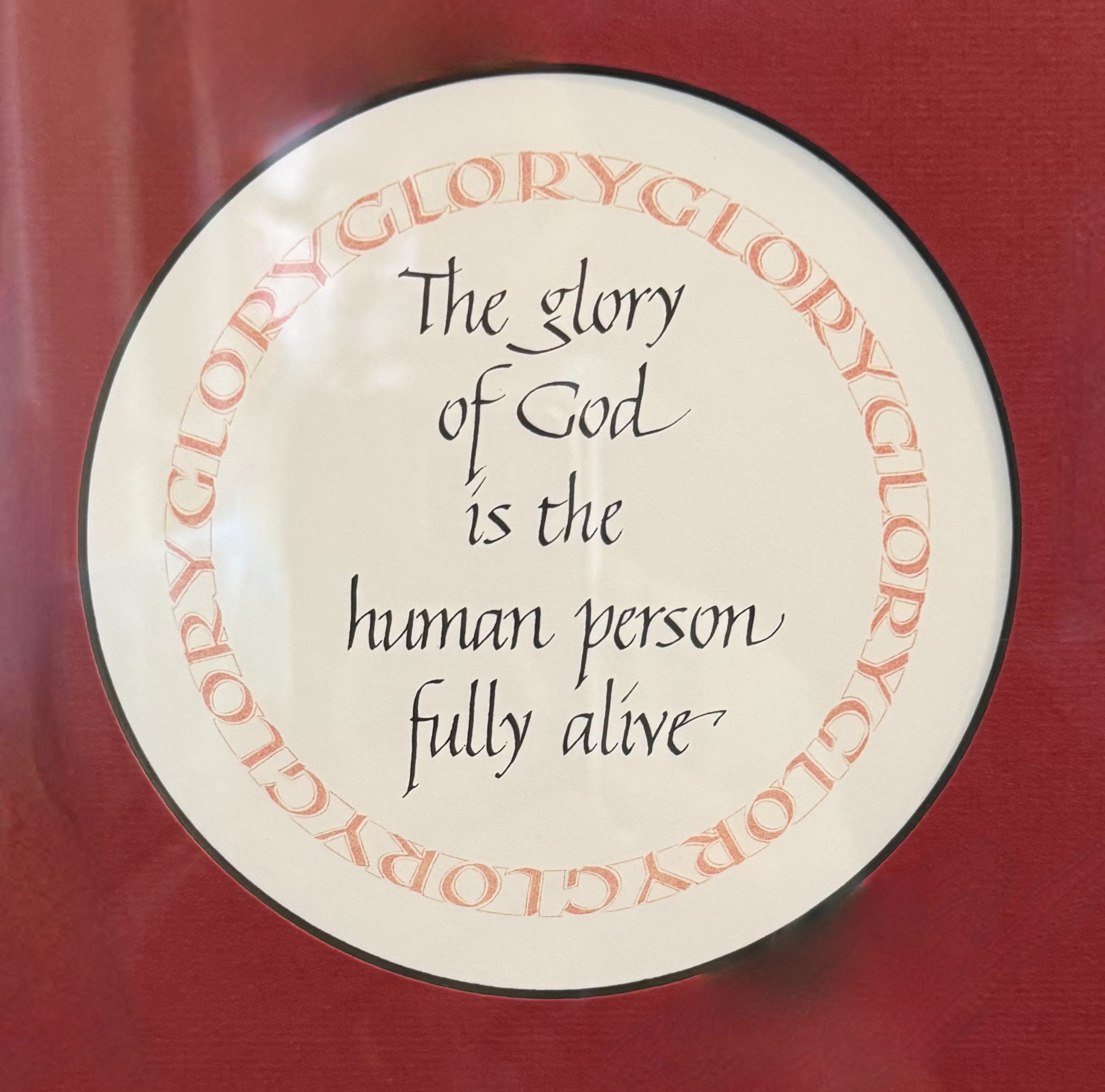

We had personally witnessed a touching illustration of what I believe Jesus was getting at in his parable found in Luke 18:9-14, often called The Pharisee and the Publican (or Tax Collector). This parable and other related Gospel sayings or stories are often described as providing us with illustrations of God’s love for us, and of what God’s love for us seeks to nurture in and elicit from us. To me, an often missing word in such characterizations of Jesus’ vision and teaching is ‘beautiful.’

I doubt I will ever forget an observation made by a young aspirant to ordained ministry, about her loss of her father following his lengthy terminal illness: “it is a beautiful thing to have someone for whom you mourn.” There is a similarly strange beauty – and ‘strange’ because it is unexpected – to be found in offering, or in being invited to receive from a friend, grief-filled repentance. Otherwise, we are rarely ever so self-disclosing, so without guile and, hence, so vulnerable. Perhaps the beauty we find here in such moments is the reflected beauty of the divine nature, in whose image and likeness we have been created.

But the loving light of that same divine nature also illumines how our created likeness with God is now marred, and often obscured. This is what can keep us holding our hurts within, while foolishly thinking we are somehow different from others.

And then, on an occasion that can be a surprise even to the one who offers a painful admission, the reflected beauty of the divine nature is briefly revealed, shared, and there before us to behold.

When we find ourselves moved to share our pain and grief by our acts of repentance, we may experience a paradox. We may find that, in the embrace and assurances we receive from those with whom we have been candid, we have received something of even dearer value to us. We may find that we have received a beautiful gift, the gift of experiencing having been found by the One who has come to find us.

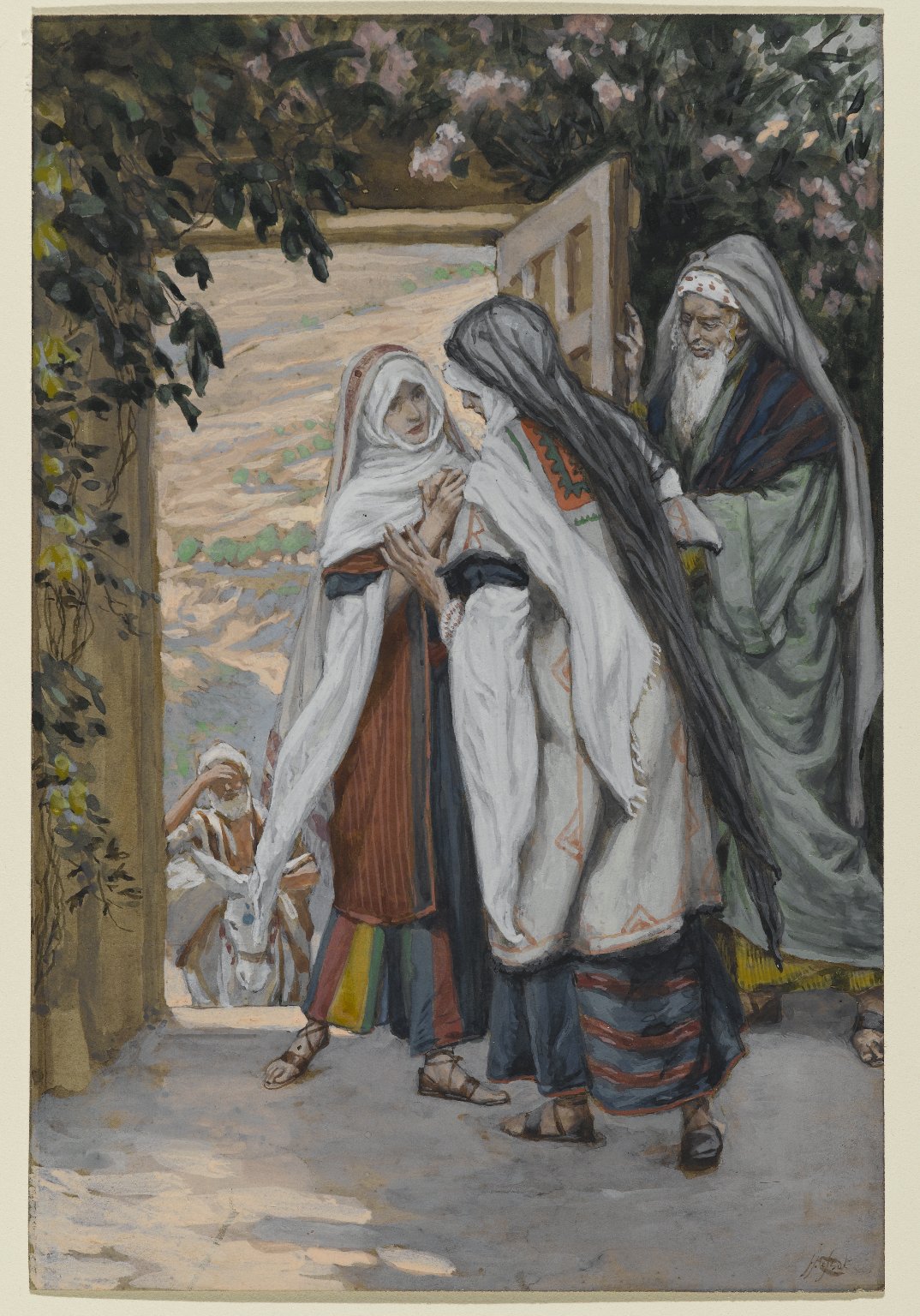

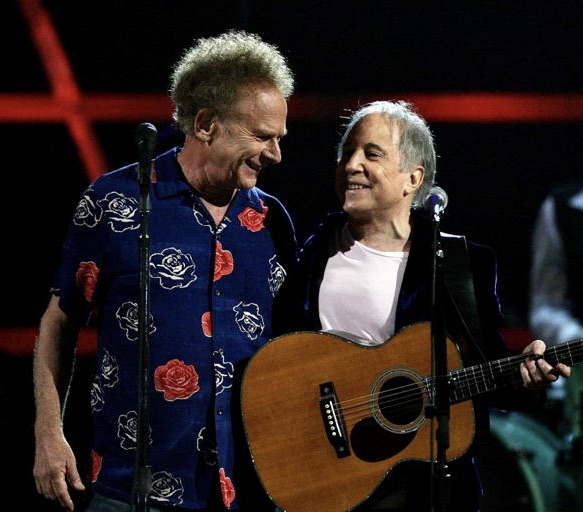

James Tissot, The Good Shepherd

Additional note: Jesus’ teaching, “blessed are those who mourn,” might best be understood in relation to the grief we can experience accompanying our acts of repentance. Charles Wesley may have had this idea in mind when composing verse 2 of his text for the hymn/poem, “Lo! he comes with clouds descending.” For we are close to the Father’s heart when our grief is born of sincere repentance.

Every eye shall now behold him, robed in dreadful majesty;

those who set at nought and sold him, pierced, and hailed him to the tree,

deeply wailing, deeply wailing, deeply wailing, shall the true Messiah see.

(Charles Wesley, in the words of Hymn 57 in The Hymnal 1982)