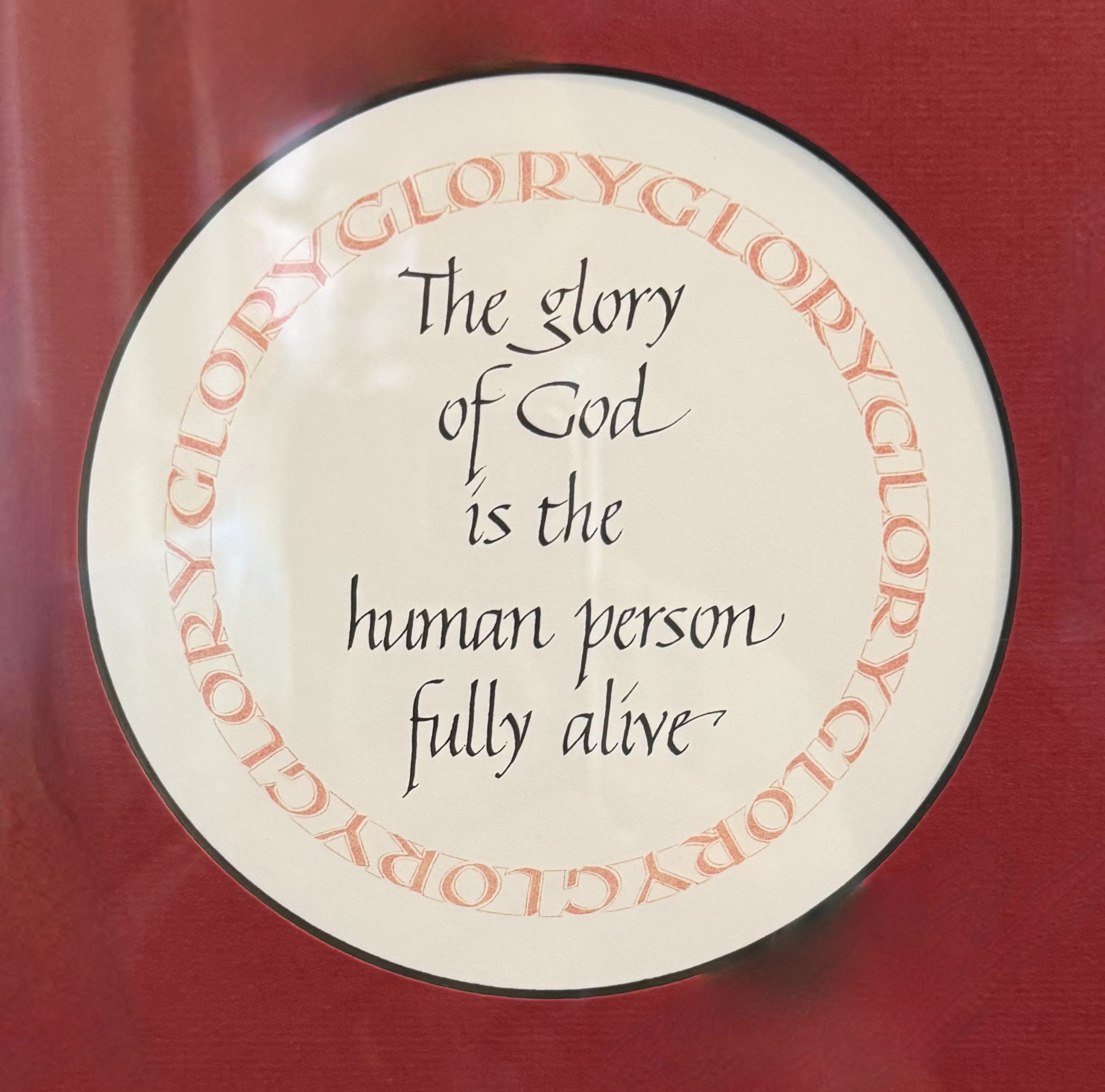

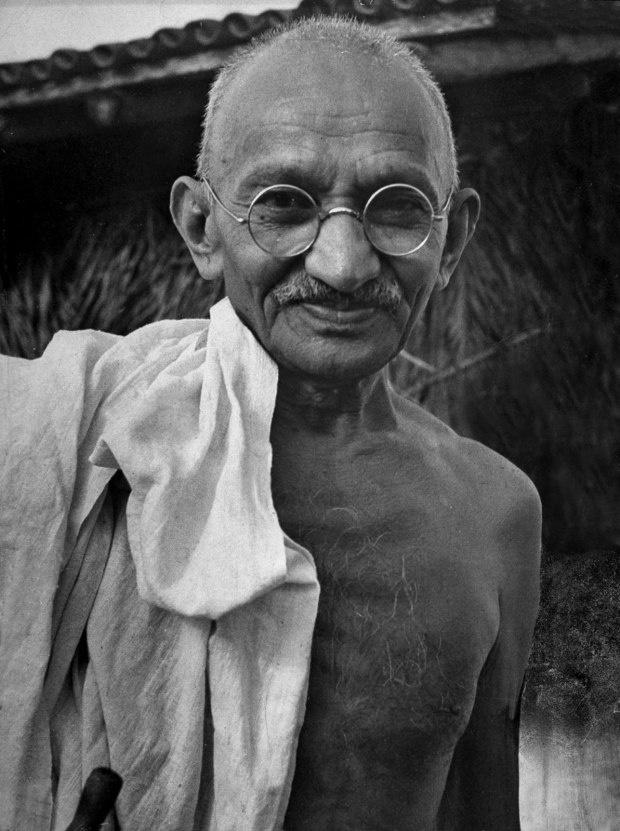

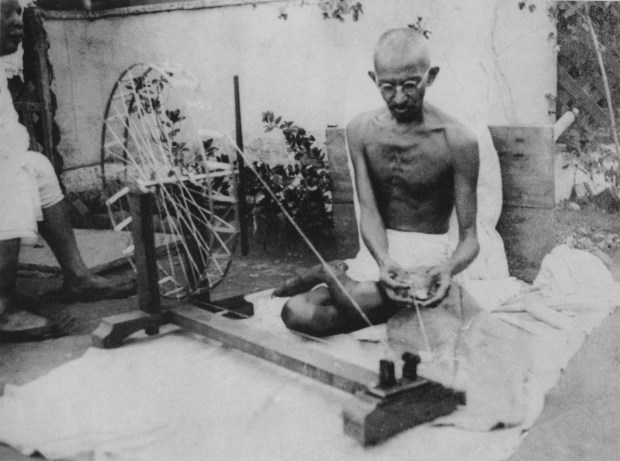

A photo of a print given to us years ago

Those familiar with my writing and ministry may not be surprised by how I choose to address the theme of beauty in relation to the human nature we all share.

My response is captured in a quote with words I have long loved and have frequently cited. The quote is from the second century Christian theologian and Bishop of Lyons (in present-day France), Irenaeus. “The glory of God is the human person fully alive.” To which he added, “and to be alive consists in beholding God.”

What an audacious statement! I believe that the fundamental insight here, latent within Irenaeus’s words, stems from the Gospel of John, with whose author Irenaeus likely had a personal connection. That would have been through Polycarp, Bishop of Smyrna (presently, Izmir, Turkey), the city where Ireaneaus was born. One writer has described Irenaeus as the spiritual grandson of the apostle John.

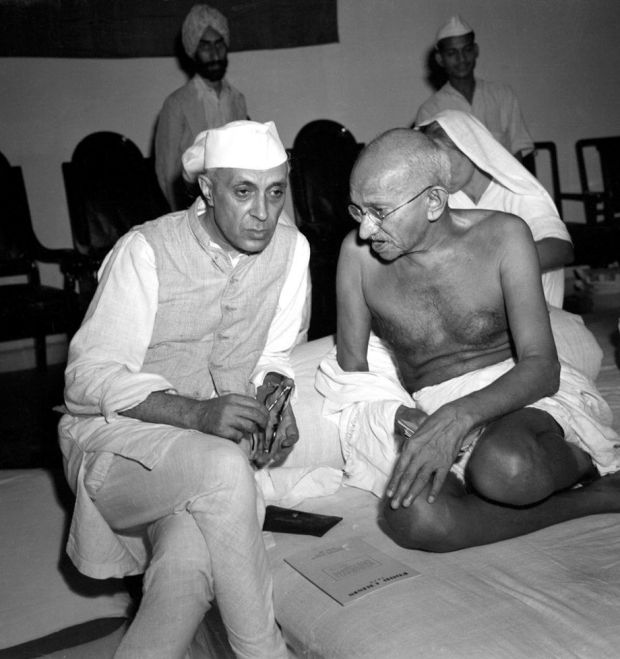

Another calligraphy print, this one featured on the website of Holy Cross Monastery

What does it mean for any one of us to be ‘fully alive’? I believe that the Gospel writer, John, would respond by echoing words from Paul, whose letters frequently employ the phrase, “in Christ.” Through Baptism, we come to be in Christ. Through Baptism, we are re-born in Christ; we live in Christ – and he in us – and we will leave this mortal life in Christ. Indeed, in John’s compelling witness to Jesus’ teaching, we are told that those who believe in Jesus have already died, and now, will never die! All of the Gospel readings appointed for funerals in The Book of Common Prayer are from John. This is the Gospel that is so centered upon the themes of God’s incarnation within our shared human nature, giving us God-given light, and eternal life.

Words found in the daily pattern for Morning and Evening Prayer, as well as in the Eucharistic pattern used on most Sundays in Episcopal Churches, help amplify this point but in a subtle way. These several patterns for corporate and individual prayer include forms for confession. Using these forms, and after we acknowledge our sin, we pray that we may delight in God’s will , and walk in God’s ways. In the absolution that follows, we hear these remarkable words:

Almighty God, have mercy on you, forgive you all your sins through our Lord Jesus Christ, strengthen you in all goodness, and by the power of the Holy Spirit keep you in eternal life.

In words that may be easy to overlook, we pray that by Holy Spirit power, God will “keep us in eternal life”! Being fully alive involves delighting in God’s will, walking in God’s ways, and being kept by God in eternal life.

Christians believe that the beauty of our human nature was and is found in the Gospel Jesus, and as the Risen Christ comes to be found in us. Our human nature, created in the image and likeness of God, and transformed to become an icon of Christ, is therefore all about the fulfillment of our divinely-given and imbued potential. When by grace we see it happen in people’s lives, it is a beautiful thing to behold.

Yet, human nature, being still what it is, prompts us to look for beauty in outward terms when we view others, as well as ourselves. Jesus, as the Gospels imply, always looked for beauty within – the kind of beauty it was his vocation to share and re-enable in us. This is what we should be looking for, both within ourselves and in others.

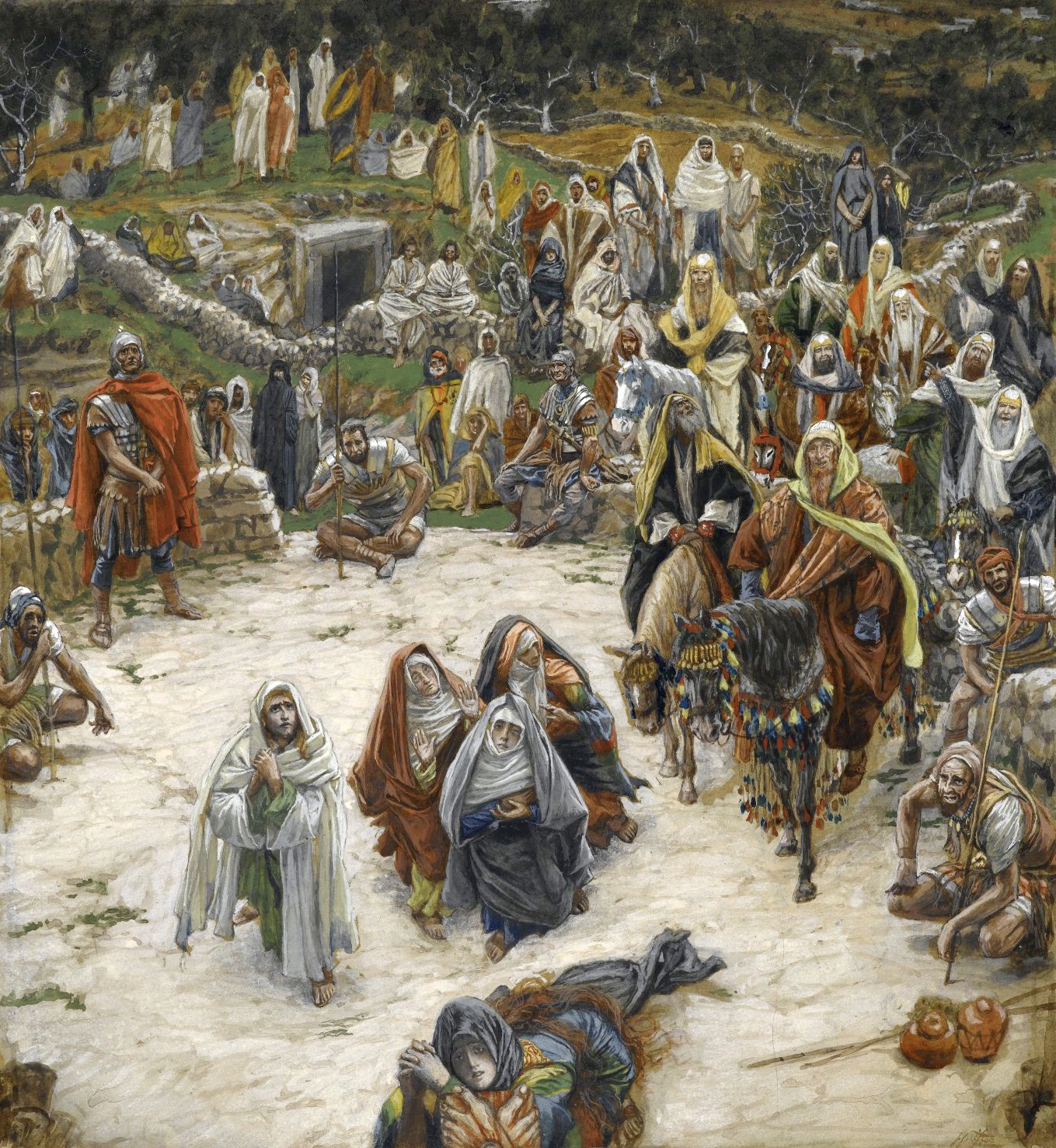

The archetypal biblical example of the glory of God beautifully manifest in human nature is found in the Gospel Transfiguration stories. James Tissot, one of my favorite painters, offers us glimpses of Jesus manifesting this same glory on several occasions, a glory that was otherwise often hidden within him.

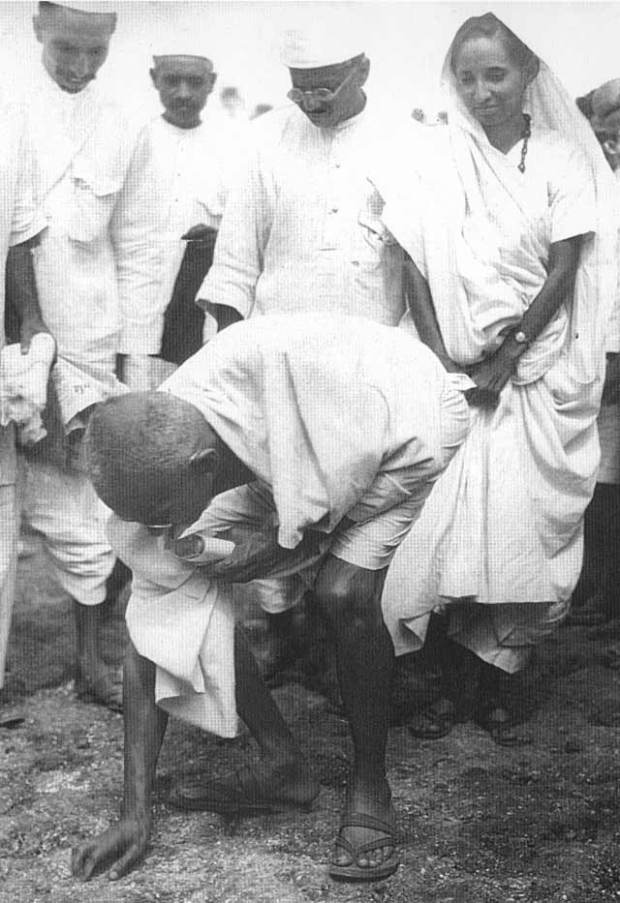

James Tissot, Jesus Goes Up Onto A Mountain to Pray

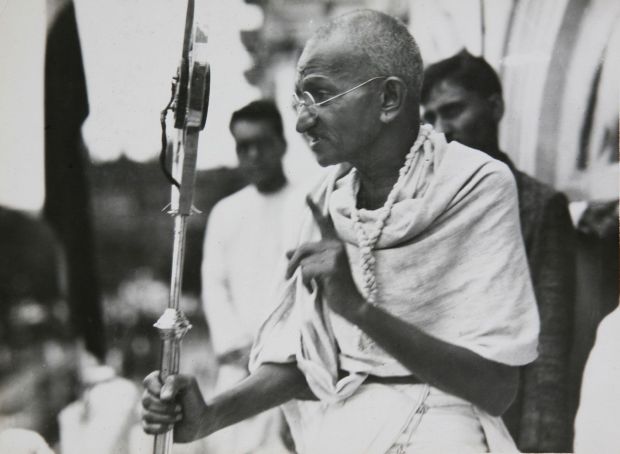

Tissot, Jesus Being Ministered to by the Angels

Paul’s remarkable words to the Corinthians bring these themes together nicely. For we want to be among those who are:

seeing the light of the gospel of the glory of Christ, who is the image of God… For God, who said, “Let light shine out of darkness,” has shone in our hearts to give the light of the knowledge of the glory of God in the face of Jesus Christ.”

And, by God’s generous grace, the same may be seen in our faces, as well.

Note: Kenneth Kirk, the esteemed 20th century Bishop of Oxford, and former Regius Professor of Moral Theology at the historic university in that city, titled one of his still-used books (The Vision of God) based on the Irenaeus quote, featured above. Kirk presents Irenaeus’ words in this (now dated) way: “The glory of God is a living man, and the life of man is the vision of God.”