[If reading this by email, please tap the title at the top to open your browser for the best experience. Then, clicking individual pictures will reveal higher resolution images.]

James Tissot, Jesus Goes Up Alone Onto A Mountain To Pray

In a painting whose title refers to one of Jesus’ common practices, James Tissot portrays him as caught up in prayer, an involvement he widely encouraged his followers to pursue. Regarding prayer, the Catechism in The Book of Common Prayer may surprise us. To the question, what is prayer, we find an answer which begins with these words: “Prayer is responding to God…” Jesus modeled a life wholly centered on responding to God, in heart and mind, in soul and body. On one occasion, he appeared transformed while at prayer. Over time, his followers discerned how God was fully present within him.

The story of his Transfiguration on a high mountain, reported in the first three Gospels and commemorated this past Sunday, provides a narrative demonstration of this truth. What Tissot depicts regarding Jesus when alone at prayer was later revealed semi-publicly on that mountain in the company of Peter, James, and John, as well as with the heavenly apparitions of Moses and Elijah. It was then fully revealed in Jesus’ Resurrection appearances.

Exodus 24 provides the background for this, and tells us something astonishing: “Moses and Aaron, Nadab and Abihu, and seventy of the elders of Israel went up {Mt. Sinai}, and they saw the God of Israel.” In Exodus 34, we learn that when Moses came down from the summit, “the skin of his face shone because he had been talking with God. When Aaron and all the Israelites saw Moses… they were afraid to come near him.” The text suggests that Moses then started putting a veil over his face for the sake of those who were unused to, or unprepared for, the glory and power of God’s immediate presence.

Paul, in 2 Corinthians, extends and also alters this idea of the veil. Instead of it being a means to protect people from a direct encounter with divine glory, the veil has become in Paul’s letter a kind of impediment. When our hearts and minds are not open to God, nor sensitive to God’s power, we become hardened. We become hardened in such a way that our hearts and minds are veiled, preventing us from perceiving God’s glory.

But Christ has set aside this veil. As a result, “all of us, with unveiled faces, {see} the glory of the Lord as though reflected in a mirror (2 Cor. 3:18).” And we “are being transformed into the same image from one degree of glory to another, for this comes from the Lord, the Spirit.” Through prayer, we also are transformed.

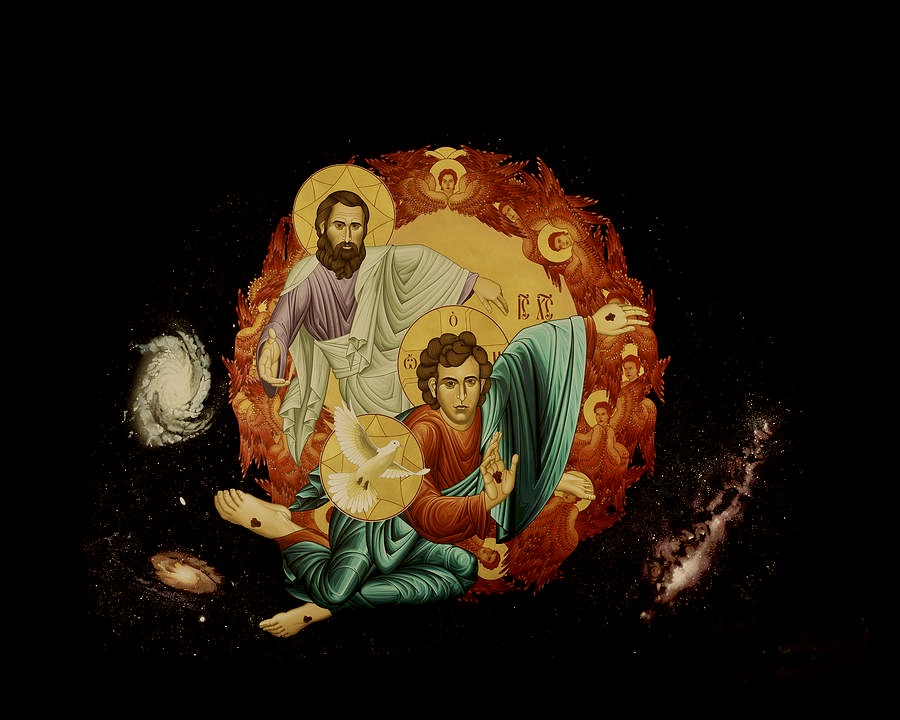

Fra Angelico, The Transfiguration (San Marco, Florence)

The Transfiguration of Jesus is all about the unveiling of God’s glory. Jesus takes Peter, John and James up with him on a mountain to pray. While he is praying, the appearance of his face changes, as does his clothing. In contrast with the Exodus and Pauline images of light shining on a surface, Luke presents God’s glory as coming from within Jesus. In other words, he radiates God’s glory rather than reflecting it. Luke tells us that Moses and Elijah, who appear with him, appear in his glory. This may mean that Jesus has shared his glory with them in a way that prefigures what he will share with all of his followers after his Resurrection.

This should lead us to ask a good question: If we feel like there is a veil between us and the divine presence, where does this veil lie? Does God ‘hide’ behind a veil, either to protect us, or challenge us? Or is the veil within ourselves, formed by our spiritual blindness and our lack of openness to how the Holy Spirit imparts glory? Paul suggests that our experience may be like that of the earlier Israelites, for whom hard-heartedness caused them to be blind to the bright light of God’s glorious presence, whether in Moses’ face or when reading and hearing the Law. Hard-heartedness can be equally blinding for us, veiling the glory that is all around us.

And where, according to Paul, do we find this glory? We find it in the faces of everyone who has been open to God’s transforming Spirit. In other words, we can find it in each other, as well as in ourselves. For this reason it can be like looking into a mirror, as the glory that we will perceive in others is the same glory that they can perceive within us.