[If reading this by email, please tap the title at the top to open your browser for the best experience. Then, clicking individual pictures will reveal higher resolution images.

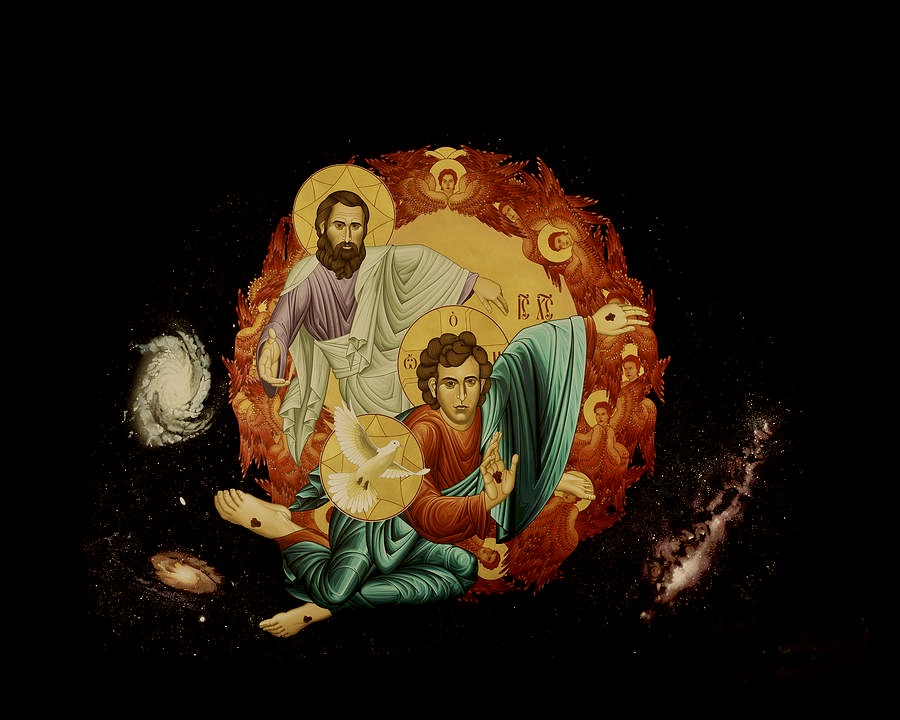

Christ Pantocrator ceiling mosaic from the Hagia Sophia, Istanbul

Advent beckons! Or does it? Isn’t something profoundly new lying just around the corner? Or shall we simply drift into another season of the old and familiar that might or might not live up to our expectations?

This calendar year, with a full week between Thanksgiving weekend and Advent Sunday, we have an ample opportunity to ponder questions like these. If such have recently occurred to you – or seem relevant now – I have a suggestion. It is prompted by a question recently put to me. What book or devotional might I recommend for Advent? My suggestion for Advent reading is John’s Revelation! It is the last book of the Bible, but arguably the first book for a new era, as we begin a new church year. And Revelation makes for unexpectedly good reading during these days of increasing darkness, at least as daylight hours are typically reckoned.

The best way that I know for begining to appreciate John’s Revelation, and read it for personal enrichment, is to engage it guided by Eugene Peterson, translator of The Message version of the Bible. Peterson helps us by making the texts of Scripture accessible and familiar-sounding. He is especially helpful in steering us around or away from what is ironically a rather modern and limited way of reading the biblical text. With him, we can avoid a literalism overlaid by misguided assumptions regarding prophecy and history. For Revelation does not contain a code to be deciphered but a message of love to be received, however strange John’s language and imagery may strike us at first.

John’s Revelation is metaphorical poetry that speaks truth, rather than something like a roadmap conveying predicted facts about what lies ahead. And so, it is not about how or when ‘the End’ will come, as if John’s book was and is about the terminus or stopping point of history and of all that we know. Instead, and in a rather more profound way, we might with John begin to see something new: how the end or point of fulfillment for all of history and of God’s purposes have in some sense already arrived!

In these weeks of shortened daylight hours and increasing chill, the prospect of reading Revelation may seem antithetical to a hopeful anticipation of Christmas. Cheerful music, warm lighting on dark and cold evenings, and holiday treats on the table, are all attractive and good things for us to enjoy at this time of the year.

But if we have any sense that there is something wrong with the present state of our world, whether with things near or far away, ignoring or being in denial about such are not our only alternatives when it comes to how we might approach each new day. A new phase in salvation history has dawned, and does not simply lie ahead in an undefinable future that is beyond our grasp. Yet begining to see this new phase in God’s ongoing work of Redemption may take the work of imagination, a praying imagination as Peterson puts it, in order to see the real beauty that now surrounds us, and which can be found within.

The beauty of the face of ‘the coming One’ is already here to be seen. We don’t have to travel back in history to a stable in Bethlehem, nor do we need to try and peer ahead to some kind of future cosmic crisis to see his arrival. For he is here with everyone. And he can be seen in the faces of those who through their Baptism bear the intimacy of his beautiful presence.

Eugene Peterson’s book on John’s Revelation, Reversed Thunder: The Revelation of John & the Praying Imagination, is in print and available from book sellers. I am pleased that Amazon has announced the future release of a Kindle (ebook) as well as an audio version from Audible.