If reading this by email, please tap the title at the top to open your browser for the best experience. Then, clicking individual pictures will reveal higher resolution images.

The grave of Hamilton Sawyer, U.S.C.T. (a Civil War casualty)

I found an unanticipated beauty in a wintry place a short drive from my home. Port Hudson National Cemetery is easy to overlook, though one of many created by the Federal government during the Civil War to provide for proper burial of the Union dead. It helps us remember those who lost their lives during a prolonged siege along the Mississippi River in 1863.

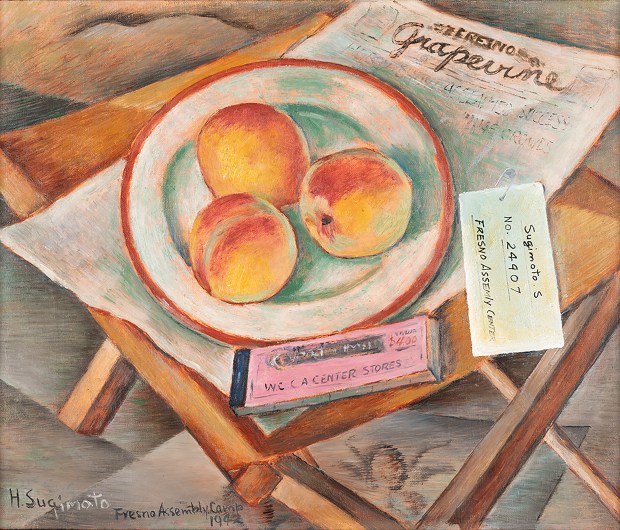

Among several thousand headstones, some include the initials, U.S.C.T. Wondering about them, I discovered they signify membership in a former United States Colored Troops regiment. Hamilton Sawyer (died 2 Feb 1864), and Samuel Daniels (died 19 Jan 1864), were two of many young men about whom history seems to have preserved only these bare facts. And yet, as a nation we remember them. Away from home and family at the time of their deaths, they surrendered their lives to help secure freedoms already declared, yet far from actualized in the lives of so many. Obviously, no contemporary visitor to the cemetery could have known either of these men. But we can – if we choose to – remember their names, and for what they died. The beauty of remembering lies in how we make present what we value.

Not everyone appreciates the beauty we find in a National Cemetery. Though these burial grounds were created and are maintained to honor those who have served in our nation’s military, these settings do not celebrate armed conflict. Instead, they venerate the commitment of many fellow Americans to serve our country and its founding principles, and commemorate their willingness to put the interests of the wider community before those of self. Most of us can recognize this commitment and willingness, even if we are not all moved to prioritize these things among our choices.

Praiseworthy themes often characterize eulogies offered at funerals. On such occasions, people usually identify and highlight the admirable traits of those who have died, whose lives we seek to honor through acts of remembrance. When done well, eulogies provide portraits of people’s lives conveying an appreciation for ways that certain moral principles and spiritual values have been lived out by them. These occasions would be drab and shallow if they merely recalled how a person consistently obeyed civil laws or always observed proper manners and social etiquette. By contrast, we touch upon beauty as we seek to remember people when they were at their best. For as Irenaeus put it, “The glory of God is the human person fully alive.” This is how we desire to be remembered.

Because of this holy desire, we choose patterns for Christian burial that anchor our remembrance of persons in the body of Christ, in the Eucharistic context of God’s redemptive work. Eucharistic remembering is both holy and thankful remembering. As such, we include an appropriate Gospel reading, and offer reflection upon it. Making connections between enduring Gospel truths and how they have become actual in the dear but transitory aspects of a deceased person’s life, is most fitting. For the sake of those gathered, the focus of a funeral homily will then best be upon what the Resurrection of our Lord has made real for all people.

To honor someone in this liturgical way upon his or her death is genuine remembering, and reflects our natural and common desire to respect a person’s unique memory. In the proverbial Anglican “both-and” way, we can keep a focus on the Resurrection, as we also express our regard for the deceased. We do this by centering our liturgical observance upon the Gospel, while focusing our intentional gathering before and after the funeral liturgy upon the person being remembered. For these different but interrelated aspects of the day belong together.

Here is something else to notice. There is a discernible symmetry between the way different baptismal candidates wear similar white robes, the way that variously styled caskets are covered at separate events by the same pall, and the way our burial liturgies – sacred and secular – ‘clothe’ our departed with the same words, on occasion after occasion. We find a pattern similar to these examples at our National Cemeteries, in how formerly high ranking officers and the lowest ranking enlisted men and women all have essentially the same headstones. In life and in death, we are – in the end – all one. Remembering the people whom the stones commemorate, even those we did not know, makes bigger our appreciation for the beauty of God’s world, and our own place within it.

To remember, and be remembered, can be holy acts. In remembering – even with regret-tinged memories – we reflect our desire for things to become whole, and brought to their fulfillment by God.

Historical note regarding Port Hudson:

From the above information plaque: “In May 1963, Union Gen. Nathaniel Banks landed 30,000 soldiers at Bayou Sara north of Port Hudson {at St. Francisville}. A force of 7,500 men commanded by Confederate Gen. Franklin Gardner held the Mississippi River stronghold. General Banks’ May 27 assault on Port Hudson failed and nearly 2,000 soldiers died. Among them were 600 men from two black regiments–the 1st and 3rd Louisiana Native Guards.* The Port Hudson engagement was among the first opportunities for black soldiers to fight in the Civil War. Their determination proved to the North that they could and would ably serve the Union Cause.”

“Among those buried {at Port Hudson} are 256 men who served in the United States Colored Troops (USCT).”

*Additional note from an informative Wikipedia article: “The 1st Louisiana Native Guard was one of the first all-black regiments in the Union Army. Based in New Orleans, Louisiana, it played a prominent role in the Siege of Port Hudson. Its members included a minority of free men of color from New Orleans; most were African-American former slaves who had escaped to join the Union cause and gain freedom.”

Port Hudson National Cemetery on a summer day

Note: blog settings have been changed to provide more opportunity to offer comments, using the link below.