If reading this by email, please tap the title at the top to open your browser for the best experience. Then, clicking individual pictures will reveal higher resolution images.

In late 1987, two American college students were exploring the jungles of Columbia. After obtaining a canoe, they embarked upon the Putumayo River and strayed into territory held by a Marxist rebel army. Formally known as FARC, these guerrilla soldiers abducted the students and held them captive for ten months in various jungle camps.

At first, the FARC guerrillas thought the two men were CIA agents, though the students corrected this. But then their captors came to see them as hostages having economic value. Soon, their parents hired an American explorer, who found the hostages and their captors. After four months of negotiations, conducted by a Roman Catholic Bishop, the students were released and taken to the American Embassy in Bogata.

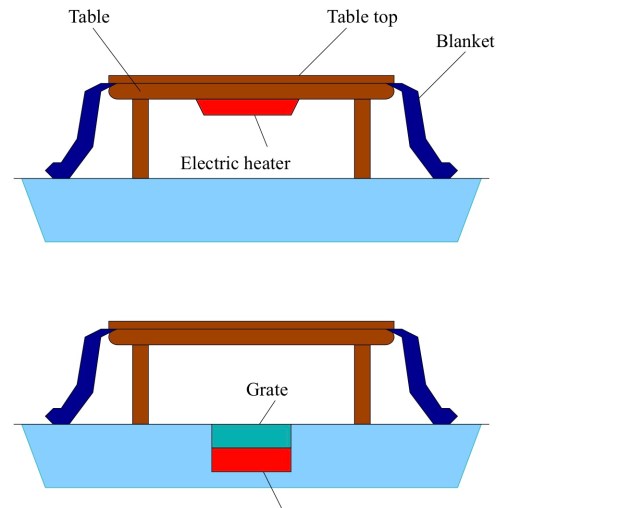

Release for the young explorers surely came about through the payment of money, probably a lot of it. Ransom is a way to describe this kind of payment, where something valuable is exchanged for the freedom of captives. John Everett Millais’ painting (above), The Ransom, depicts a father handing over of fistful of jewelry and a bag of coins to some men who have taken his daughters hostage. Revolutionaries, terrorists, and criminals have long used ransom as an efficient means of fund-raising, especially when their captives come from wealthy families or are politically well-connected.

Clearly, when payments are made to captors, the purpose is not to honor or reward the hostage-takers. Instead, these payments reflect an abiding concern for those who are held-captive, awaiting redemption.

This concept of ransom is deeply rooted in our Judeo-Christian tradition, and it shapes how we understand redemption. Think of the beloved Advent hymn, which begins this way: “O come, O come, Emmanuel, and ransom captive Israel…” In the Old Testament, in many passages like Psalm 49; Isaiah 35, 43, and 51; Jeremiah 31; and Hosea 13, we hear about how God’s promises inspire hope for the possibility of ransom from the power of death.

These insights help us understand Jesus’ words about ransom in Mark’s Gospel (in 10:45; parallel in Mt. 20:28). After predicting his suffering and death three times, Jesus tells the oblivious disciples that “the Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many.”

Yet, instead of a ransom-based understanding of Jesus’ sacrifice and death, many Christians think of Jesus’ saving work in a largely legal or juridical way. In this view, our sin involves a degree of corruption and guilt so bad that it’s beyond what we can make right. And so, human captivity to sin means that ‘a penalty must be paid, and punishment meted out.’ By this reckoning, only a ‘sinless one’ could pay the uncountable price, and bear the penalty for all. Therefore, Christ as a substitute for us, paid the price and endured the punishment so that we, ourselves, don’t have to, even though we are the ones who deserve it. Yet, according to this very common theory, the ‘price’ was paid to God, to satisfy God’s justice!

This legal or ‘punishment-substitution’ understanding of Jesus’ death did not become widespread for at least a thousand years after his crucifixion. Instead, during the first millennium, a different concept of Jesus’ mission was preeminent. It springs from the ransom words in Mark, as well as from 1st Timothy 2:5, where Paul writes, “…there is … one mediator between God and human kind, Christ Jesus… who gave himself [as] a ransom for all.”

According to this ransom view, ever since Creation, we have placed ourselves in the hands of Satan, by refusing to ‘delight in God’s will or walk in God’s ways.’ In effect, we have strayed into ‘the jungles of sin,’ and have allowed ourselves to be taken hostage by the Devil. We are held captive by our sin, and by our inclination to follow our own will. Like the two student hostages, we might have ‘paid’ our way to freedom ~ if we and they had had the means to do so. But we did not.

And so, showing his great love for us, Jesus offered himself to the Devil, as a ransom for our freedom. Jesus allowed the Devil to take him, as someone of even greater value than all of us. For Satan received as a ransom the sinless One, God’s own son. C.S. Lewis employs a similar ransom metaphor in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. In this biblically-derived approach, the ‘price to be paid’ was a concession to the power of an enemy, and compensation for a loss, rather than (as in the later and more prevalent legal view) a payment to satisfy God’s sense of justice.

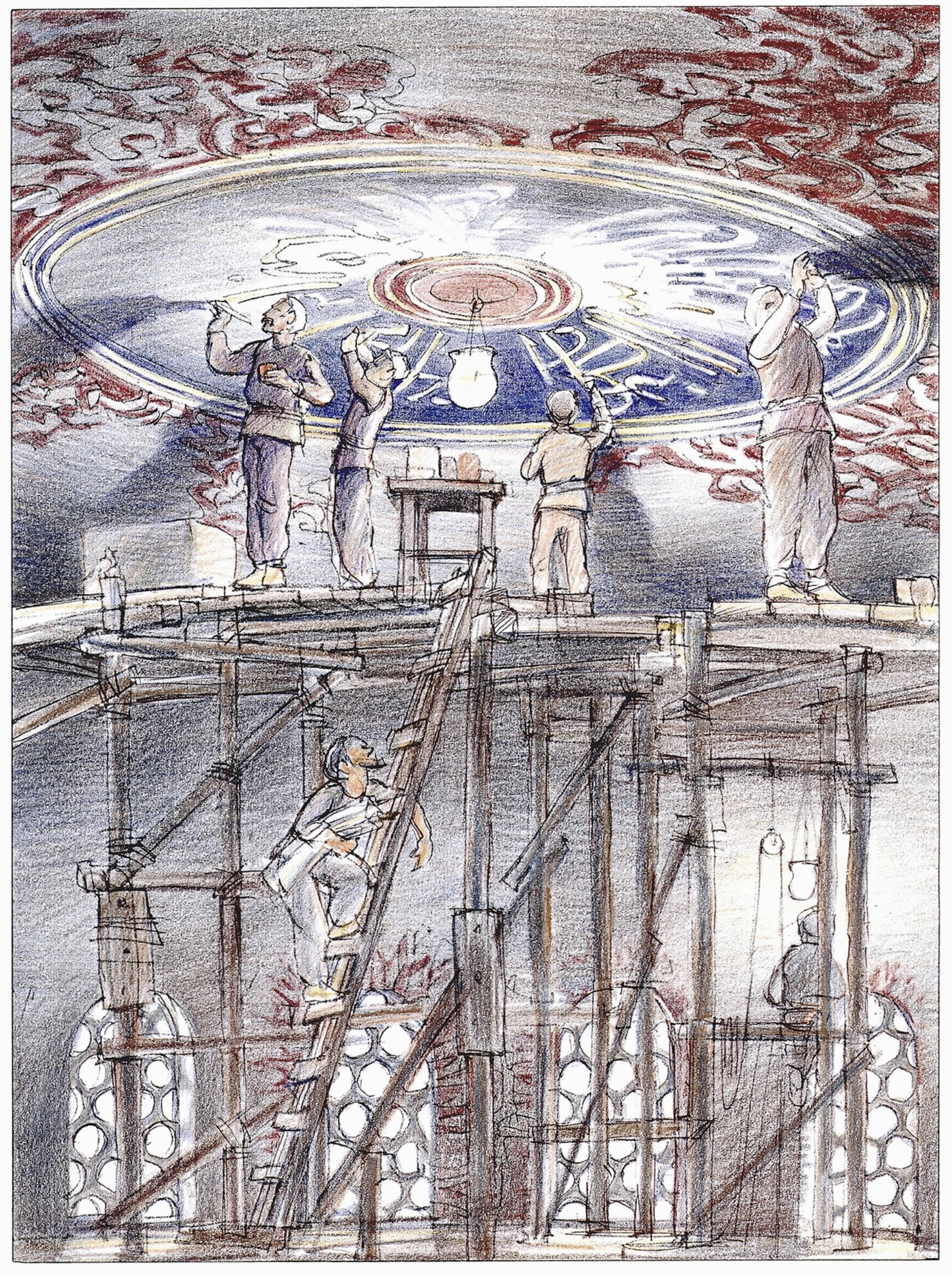

An image of Aslan’s self-sacrifice, from a film version of The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe

This post is adapted from some material previously published in this space, with some additional imagery. It is based on my homily for Sunday, Oct. 20, 2024, which may be accessed by clicking here.