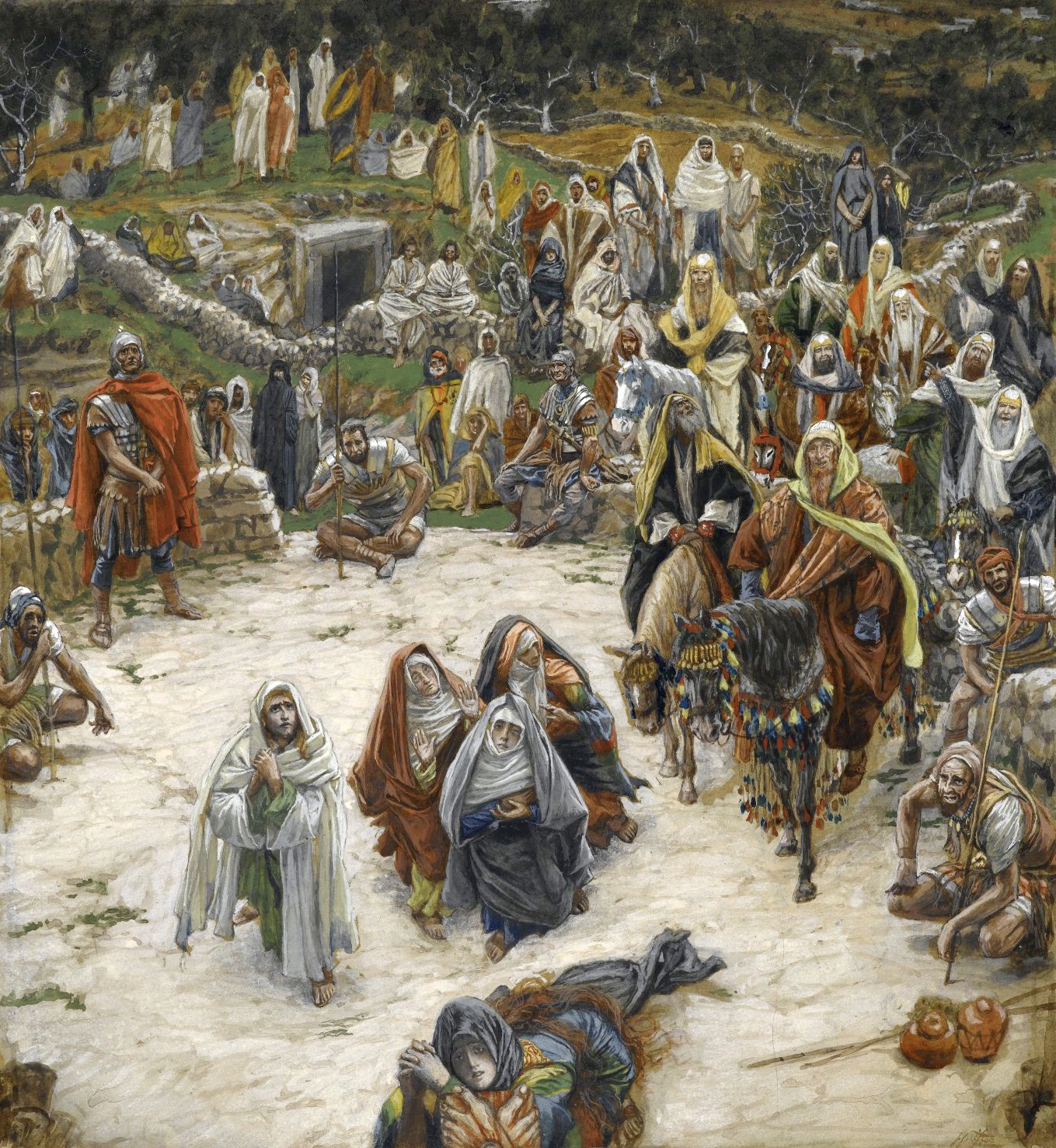

In preparing to offer an autumn class through an LSU seniors learning forum, I have been reflecting on the general themes that animate this blog website — art, beauty, and transcendence. The link between art and transcendence is intriguing, and for many of us, it is something we experience. Yet, the alluring and knowable significance of beauty – linked here with art and transcendence – is harder for us to get at. Relying upon a famous historical quote that some will recognize, I will paraphrase the matter this way: I can’t define Beauty; but I know it when I see it!

Readers of this blog will have noticed my prior exploration of what may be a common sequence or pattern in life experience. Through it, we move from encounters with Beauty, on to reflection about what may be Good. This then can lead to a search for, and reflection upon, what is True. These three facets of this transitional sequence, Beauty, Goodness, and Truth, are also referred to as the “Three Transcendentals.” They have been portrayed in art history as the Three Graces, in the form of three young women appearing together as in a dance.

We may infer something from this common association between Beauty, Goodness, and Truth, in relation to the further category of that which is transcendent. The three so-called ‘Transcendentals’ at least verbally have something to do with our human interest in the compelling category of transcendence. [Note: transcendental and transcendence obviously come from the same root word.] For our experiential encounter with some objects and or events can lead us to describe them as having been memorably beautiful, very good, and or compellingly true. Why? Because when remembering these encounters as occasions in which we glimpsed, sensed, and or apprehended something real and beyond sense experience, we have had an engagement with what we may best describe as having a ‘transcendental’ quality.

One way to help account for the above is to recognize that we are ‘spiritual’ beings, and not merely animate beings whose significance can be explained solely in terms of bio-physical data and analysis. To help get at the questions we are exploring, we can refer to the long-recognized brain-mind question. Does human conscious experience terminate with brain function? That is the blunt way to put a matter that can be so much more suggestive and evocative. Our human experience – here and now, in our conscious awareness – clearly depends upon brain function. But what if it also transcends brain function?

Here, we can fall back upon a basic principle of received Christian doctrine: we are embodied. In life beyond, if it is granted to us, the New Testament tells us that we will remain ‘embodied,’ though not in the same form as we are now. So, if brain function demonstrably ceases upon physical death, and if consciousness may transcend the cessation of brain function, what might we make of this?

My reflections on these ideas have led me to a further perception, which may call for additional consideration. When we have encounters with objects, experiences, and or events, that we describe as highly beautiful, movingly good, and or compellingly true, we have experiences of not only what is here and now, but also of what may be transcendent. In having such experiences, we often feel more true to our selves, to who we are, and to whom we hope to become. And the world feels more real and true in an expanded way. In the process, we may become more transparent to ourselves.

Stemming from such experiences, I find that I am also more open to being transparent with others. How? Sensing I have encountered something truly beautiful, genuinely good, and or fundamentally true, I feel more alive, and more in touch with the way the world really is. These experiences leave me more sure about my perceptions of what I have sensed. I then find I am more confident about these experiences, and more willing to share them – and myself – with others.

Experiencing Beauty, apprehending Goodness, and discerning Truth, may therefore open the doors of communication we yearn to have with others.

My thanks to a longtime friend, Chip Prehn, and to my brother, Greg, for the above photos. The first three come from Sassafras Farm, during haying season in Virginia, and the latter photo was taken while my brother was recently completing his fourth Camino de Santiago.