If reading this by email, please tap the title at the top to open your browser for the best experience. Then, clicking individual pictures will reveal higher resolution images.

James Tissot, The Magi Journeying (detail)

Instinctively, there is something we all seem to seek. We want to find purpose and meaning, and organizing principles for our lives. This desire is anchored in a larger one: we seek to discern what is real, and true.

But where does our common impulse come from? In what does this impulse consist? I think the best answer to these questions is found at the heart of the Feast of the Epiphany. On Epiphany, we celebrate how God has revealed to the world the real and true meaning and purpose for our lives. Epiphany is all about God revealing to us the divine center of everything. Epiphany highlights God’s self-revealing in the natural world, and preeminently in God’s Incarnation, which the Magi came to discover and then worship.

We are able to recognize that it is in the nature of a Creator to order reality, imbue it with purpose and meaning, and hence to bring order, purpose, and meaning to our lives. A perhaps-unexpected word that captures this broad idea is authority, in that God possesses the authorizing power to create things, and guide them. Specifically, we discern this authorizing power in God’s creation of the universe and in the divine agency shaping ongoing history. For God is the author of all that is real and true.

In human life, authority and power are not always neatly aligned, and we experience trouble when the two are at odds with one another. We see this dialectic between the two at work in the events of Holy Week, in the confrontation between divine authority (in the vocation of Jesus), and worldly power (as exemplified by Pontius Pilate). Less obvious is the way this dialectic is manifest in the events that are commemorated in our celebration of Christmas and the Epiphany of our Lord, especially in connection with the visit of the Magi from the East.

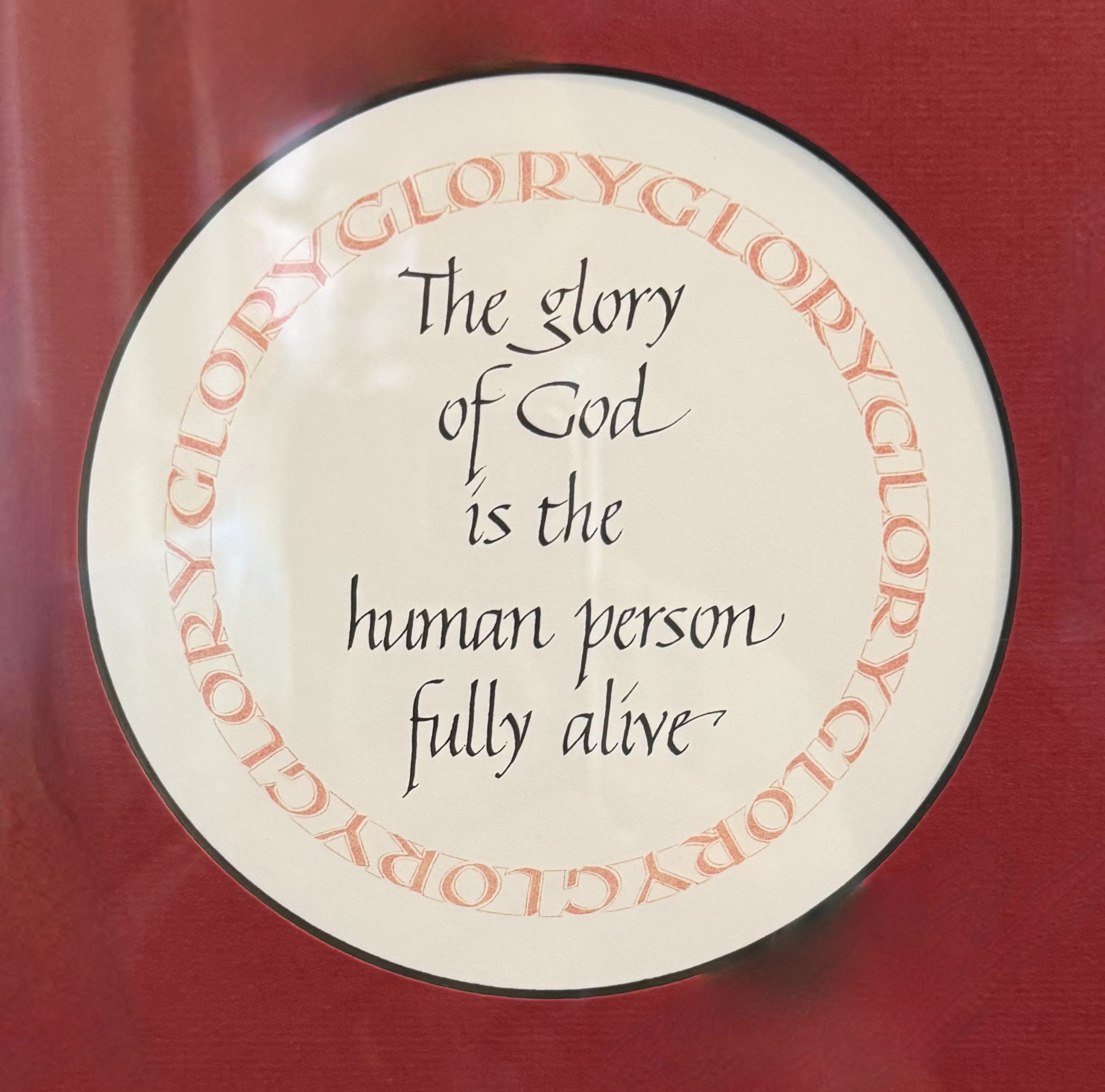

James Tissot, The Magi in the House of Herod

The Magi, also called ‘wise men,’ or ‘kings’ from the East, arrive in Israel having been guided by an authoritative power greater than themselves. Because of their witness to this higher authority and its implied power, the visitors pose a threat to Herod and his courtiers, who exercise earthly authority and its attendant power. This emerges in the interaction between people who are witnesses to divine authority and its power, and others who are possessors of worldly authority and power. The emerging conflict, later seen in the events of Holy Week, arises amidst the challenges surrounding the beauty revealed in what we call the Epiphany, the revealing of divine light to the whole world rather than to just a particular nation or the people of a particular religious tradition.

The Magi from the East, by explaining their quest, prompt Herod to act. He acts viciously and violently through orders given to soldiers under his command. The result is the series of murders we acknowledge every year on December 28, in the ‘red letter day’ we call the Massacre of the Innocents.

James Tissot, the Adoration of the Magi

What are we to make of the Epiphany of God in human form, and the tragic circumstances to which it led? At the heart of Christian belief is the conviction that God became present to us through a human birth. He revealed himself in a human person who embodied two natures, one fully divine, and one fully human, whose natures are distinguishable yet inseparable. Such a person, regardless of appearances, was and is the transcending center or heart of all that is, manifest in human form. He is, therefore, the One who truly possesses divine authority and divine power. Einstein – who was not in any sense a traditional believer – said this: “The most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious.” The divine center of reality, manifest and revealed in a human being, is the most mysterious beautiful thing that we can experience.

Here is the wonder of it: in God’s mysterious Providence, the birth of the Messiah would bring death to many (in the Massacre of the Innocents). And – years later – the death of the Messiah would bring the possibility of new birth to all, through the redemption of human being from the power of sin and death.

Yet, it would be some decades later before those who proclaimed Jesus as Messiah, and the embodiment of God, could understand the connection between his birth along with those soon-resulting deaths of the Innocents, and his later death, along with its soon-resulting new births for those who came to believe in him.

Our proper response to all this — indeed our only response to all this can and should be to praise the Holy One of Israel, the one whose death brought new life to all who receive him. He has come to us. Come let us adore him. And let us receive him with renewed hope and joyful hospitality, in all his light-filled glory.

A blessed Epiphanytide to you and your loved ones.