Errol Barron’s work as an artist may be familiar to readers of this website based on some of his evocative New Orleans water color paintings previously featured here. His paintings of that city as well as of Tulane University, where he has taught for many years, provide strong indications that he is more than a skilled painter and draftsman, but also a trained architect. He has taught generations of architectural students at Tulane, and he has practiced his profession to great effect not only in this region but also overseas, with some houses of his located in Greece. Given Barron’s evident sensitivity to historical architecture and design features characteristic of this region, I was surprised to learn about a notable but unexpected feature of his resume. He worked for seven years with Paul Rudolph, architect of the well-known and oft-criticized Boston Government Services Center and a partial inspiration for the movie, The Brutalist.

I was recently delighted to discover the Episcopal church in Gulfport, Mississippi, St. Peter’s by the Sea, and that Errol Barron was its architect. It is a gem of a church, and a very successful design that incorporates traditional ecclesiastical elements associated with European Gothic churches along with features reflecting contemporary liturgical renewal. I have heard people refer to this style of church building as Carpenter Gothic, and as Southern Gothic, and the labels seem to fit well. The worship space exudes an appreciation for traditional forms while harmoniously blending them with a contemporary focus upon light, color, and the greater participation of worshippers in flowing open spaces.

Visitors to the Washington National Cathedral, and similar churches of Gothic-revival style, may recognize the particular heritage that stands behind the floor plan of St Peter by the Sea. At the National Cathedral, and in its medieval forebears (such as London’s Westminster Abbey), an arched stone ‘rood screen’ separates the chancel and choir (beyond the screen) from the nave where the congregation is seated. When, in the 1960’s, the liturgical renewal movement began to influence changes in the worship arrangements of these buildings, a new main altar was often then placed in the nave, on the congregation’s side of the rood screen. Smaller gatherings for weekday services could still occur in the choir side of that screen, while Sunday gatherings for the principal Eucharist would be celebrated in the nave, with the clergy, altar, and liturgical action proximate and visible to the congregation.

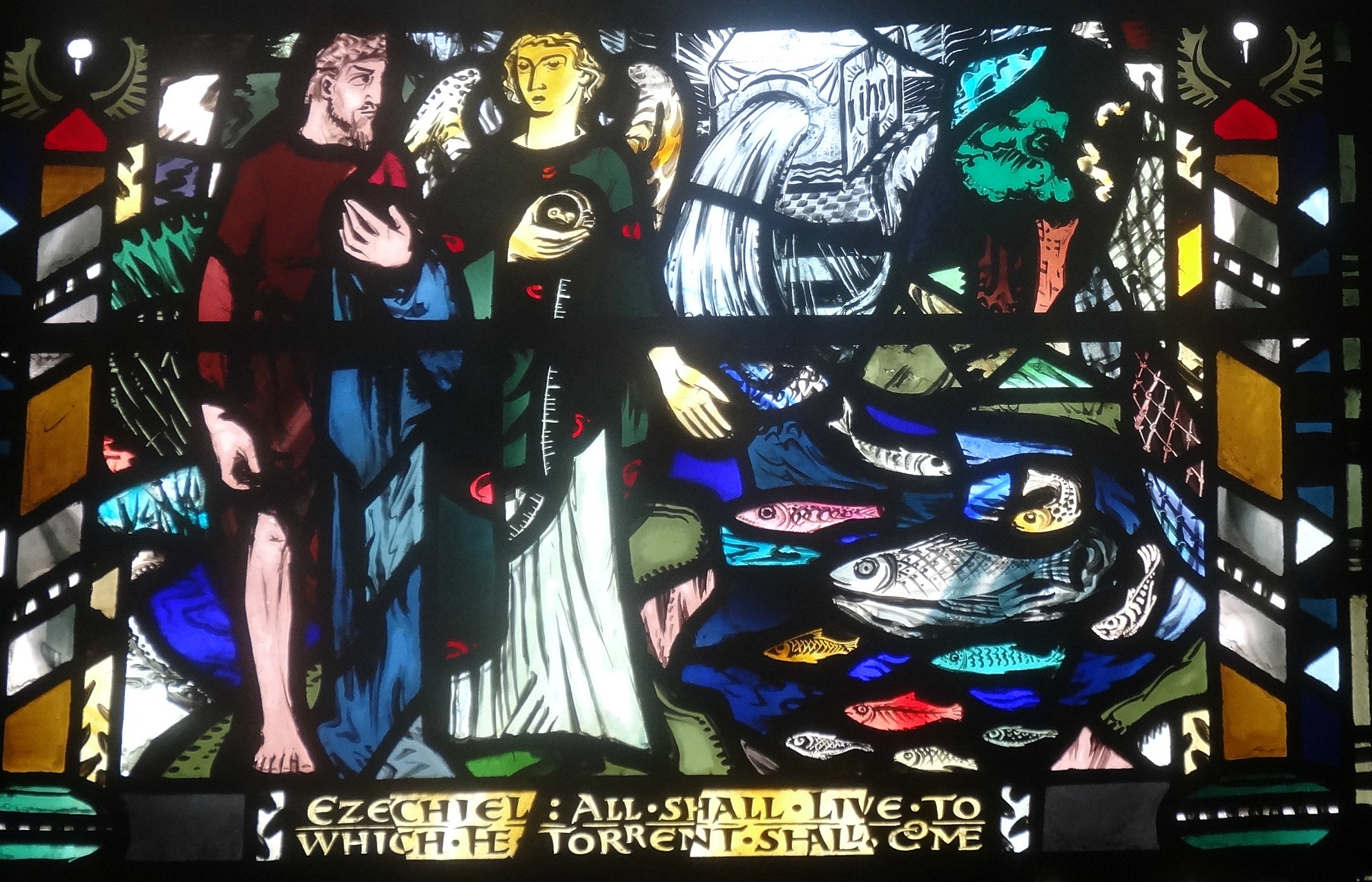

Though St Peter’s by the Sea is a comparatively recent building, its design reflects something of the historical sequence described above. Instead of an imposing stone rood screen, shielding the chancel and choir spaces beyond, Barron has designed an ornamental arched screen of light-colored wood that suggests rather than imposes separate areas within the overall space. This allows the evocative blue canopy of the ceiling over the chancel to draw one’s eyes forward, toward the visible clear windows at the liturgical ‘east end’ of that space behind the chapel altar, facing the seashore.

Further, the notably narrow, even sharp-looking, wooden ‘spires’ protruding above where the choir chairs are placed enhance the upward sense of lift in the nave, complemented by the radiant cream and white color scheme above where the congregation sits. Light pours in through clear windows above, while delicately fashioned and dangling wrought iron fixtures provide supplemental illumination for evening services and in poor weather.

On the Sunday of my recent visit, I was told that the congregation numbered about 145, and I estimate that the nave would comfortably seat about 200 people, though it could probably accommodate more. With the Gothic-inspired longitudinal floorplan, evident when one approaches the exterior of the building, a visitor might expect a rather narrow and linear worship space. Such an initial impression of the likely effect of the interior spatial arrangement is overcome by a number of subtle but effective design choices made by the architect and those who worked with him.

Accompanying the verticality of the large open area above the center of the nave are the seating areas adjoining the side aisles, taking the places of side chapels found in many medieval Gothic churches. The relatively low height of the box pews enhances the sense of horizontal width created by these adjacent seating areas, which provide relatively unobstructed views of the altar and lecterns. I also found the acoustics within the worship space to be well-suited for music as well as for public reading and speaking.

I am drawn to the ethos of historical churches; I am enthused by many examples of modern architecture; and I appreciate the fruits of the liturgical renewal movement. In my experience, a successful blend of these three things is not always found in contemporary buildings designed for worship and intended for the enhancement of congregational life. In his design for St. Peter’s by the Sea, in Gulfport, Mississippi, and in his supervision of its restoration after Hurricane Katrina, Errol Barron has achieved just such of a desirable synthesis.