If reading this by email, please tap the title at the top to open your browser for the best experience. Then, clicking individual pictures will reveal higher resolution images.

The Risen body of Christ bears the healed scars from the Crucifixion in Matthias Grunewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece.

My commitment to writing about Beauty is evident in my ongoing posts. I have also written about the connection between Beauty and Goodness as well as Truth, the three so-called Transcendentals. To use a phrase from another context, these are three things we ‘cannot not know,’ at least in principle.

As I expressed in my most recent post, in Christ we find the icon of God. For he is the icon of God’s beauty, God’s goodness, and of God’s truth. In turn, and as we are reminded during Lent, we are all called to become icons of Christ, and to seek to embody in ourselves what we find revealed and embodied in him.

Yet, of these three Transcendentals, Beauty, Goodness, and Truth, the third may be the most difficult for us to realize in ourselves, much less to try to describe. This is one reason why since earlier times people have recognized a hierarchy among these three things that we cannot not know. Among the three, beauty tends to be most evident and accessible to us, followed by goodness. The first often leads to greater appreciation for the second, and both can lead us to search for truth, however and wherever we may find it.

It is nevertheless not uncommon for us to be unsure about the presence or the nature of beauty and goodness when viewing objects, actions, or events. And we are very capable of engaging in disputes regarding such evaluations. But here is a paradox: though we may be just as unsure about how best to characterize what is true, or how to evaluate that quality in relation to ourselves, we seem to have much less hesitancy when it comes to ascribing the apparent absence or deficiency of truth in the words and actions of others.

To paraphrase a successful nineteenth century aspirant to the Presidency, grand ideas outlive those who hold them. James Garfield expressed this view just months before his assassination. Frederick Douglas was so impressed with Garfield’s principles and potential for national leadership that he led the procession onto the rostrum for Garfield’s Inauguration. Among those abiding principles and ideals was Garfield’s voiced recognition of the truth within a difference between many white Confederate soldiers and their leaders, and the black men who served in the Union Army. The former had betrayed the flag and their country; the latter did not. Ideas that help us identify and articulate things we value, like beauty, goodness, and truth, abide.

Nevertheless, for many of us, what we reckon to be true – as compared to what is beautiful and or good – is not always so clear. And yet, we believe in Truth. Even when we despair about its instantiation in general human affairs, and in the more limited spheres of our daily involvements, we believe that what is true should guide our lives and our conduct with one another. And, when it comes to what we practice as compared to what we believe or hope for, truth seems to be a principle that we more often honor in the breach.

Another paradoxical aspect of our desire to know the truth has to do with how what is true can not only be uncomfortable but even painful. A mother waiting up for a teenage son who is hours late getting home, and a husband awaiting word from his spouse who has not returned from responding to a wildfire, are likely to have mixed emotions about what they might learn when answering a knock at the door. And yet, in these and in countless similar cases, we want to know what is true, and the truth we want to know is one that is unleavened with inaccuracy or falsehood even if it is painful to hear.

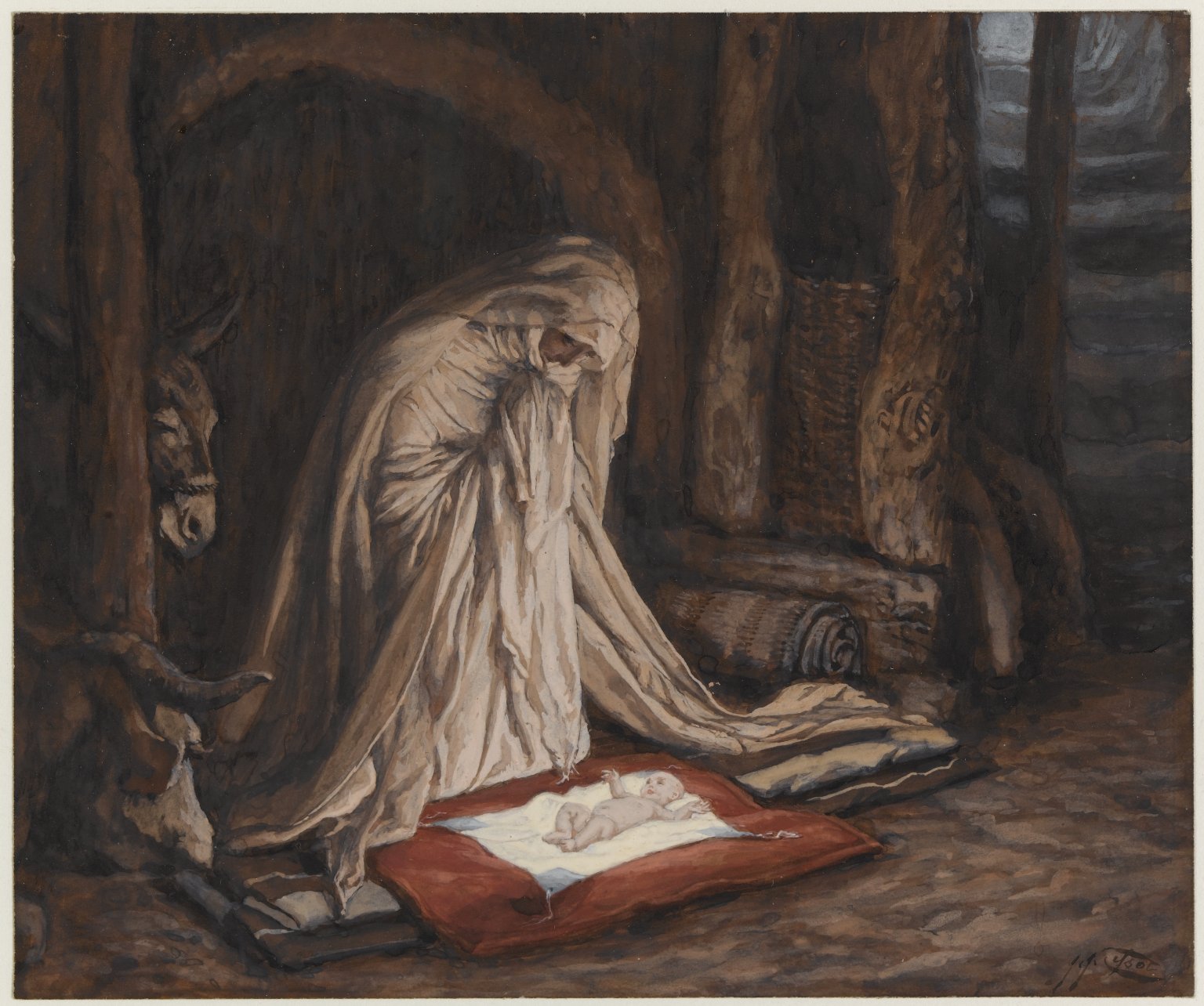

What is true can be beautiful and good, at least for those who believe in the Gospel of Redemption. This is because Christians believe that ‘facts are friendly,’ and that there is no person or situation that is outside the scope of God’s loving redemptive purposes. What personally can be hard to accept as true can still be beautiful and good. And if not so at the moment, then it can be so when we pass beyond the veil and see the embodied Beauty, Goodness, and Truth, for which we so yearn.

Heinrich Hoffman, Jesus and the Rich Young Ruler (detail)

For us, Beauty and Goodness, as the first Transcendentals, provide this experiential advantage: we find them more readily evident as they are instantiated in objects, events, and in others. Truth, by contrast, can seem more elusive and more subject to the variable preferences and uncertain powers of our apprehension. As a Transcendental, Truth – like Beauty and Goodness – has objective reality. Yet, like her sister “Graces,” Truth must sometimes, if not often, penetrate the fog of our subjectivity and experiential awareness for us to perceive it.

Additional note: I am publishing this post on Ash Wednesday, a day on which we are invited to reflect on the patterns of our lives in light of the truths we have come to know, and which have been revealed to us.

In anticipation of this coming First Sunday in Lent, I offer here a copy of a blog post with an attached homily (with related images) that I presented in a prior year, based on the Lectionary (which may be accessed by clicking here).