If reading this by email, please tap the title at the top to open your browser for the best experience. Then, clicking individual pictures will reveal higher resolution images.

Gate to the Philip Simmons Memorial Garden, Anson Street, Charleston (featuring a Simmons design)

Philip Simmons, was a blacksmith who spent his life and working career in Charleston, SC, where much of his work is preserved by homeowners, collectors, and a foundation dedicated to honoring his legacy. Along with his lifelong body of ironwork, he has been described as a national treasure. Born in 1912 in the Old South, he received a very limited education and apprenticed himself at an early age to blacksmiths he saw in his Charleston neighborhood. Eight decades of work in a blacksmith’s shop followed as he pursued what some might call a trade craft, and which in his hands was truly an art.

Mary E. Lyons has written a book about Simmons for young persons, which includes some compelling photos of his work. She offers this introduction to the artist: “Philip Simmons began his career as an untrained boy. Now he is called the Dean of Blacksmiths by professional smiths across the country. His memories show that skill and patience take years of work. They also prove that everyone can achieve both. An honored artist, teacher, and businessman, Philip Simmons is the working person’s hero.”

Though the circumstances in which he lived and worked were modest, he is warmly remembered by his home city, and he has been commemorated by a marker at the Fort Sumter and Fort Moultrie National Historical Park (shown above), by the preservation of his home and studio, as well as by a high school named in his honor. Numerous examples of Simmons’ ironwork can be seen on walking tours in Charleston, in the course of which one can enter, through a gate fashioned by Simmons, a memorial garden for named for him maintained by the Garden Club of Charleston.

An egret, one of Simmons’ favorite motifs in his ironwork

In addition to representations of egrets, other images such as palmetto fronds, hearts, fish and serpents, number among those images often featured in Simmons’ ironwork. The artist’s choice of these images reflected his sensitivity to the locale in which he was raised, both Daniel Island where he was born, and then Charleston and its low country and aquatic surroundings.

A major turning point in Simmon’s life’s work came with an unexpected opportunity brought to him when he was 64, an age when many contemplate retirement. He was invited to participate in the 1976 Bicentennial commemorative Festival of American Folklife to take place on the Mall by the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. Asked to craft a gate onsite during the event, Simmons wondered about the imagery that he might select for the project. Thinking about images that would reflect where he was from, he settled on the moon, stars in the sky, the rolling surface of water, and fish. This combination of images reflected, in his mind, the night sky sparkling upon the waters of the two rivers that form Charleston Harbor. The resulting gate, which has come to be known as the Star and Fish Gate, was purchased by the Smithsonian Institution (image below).

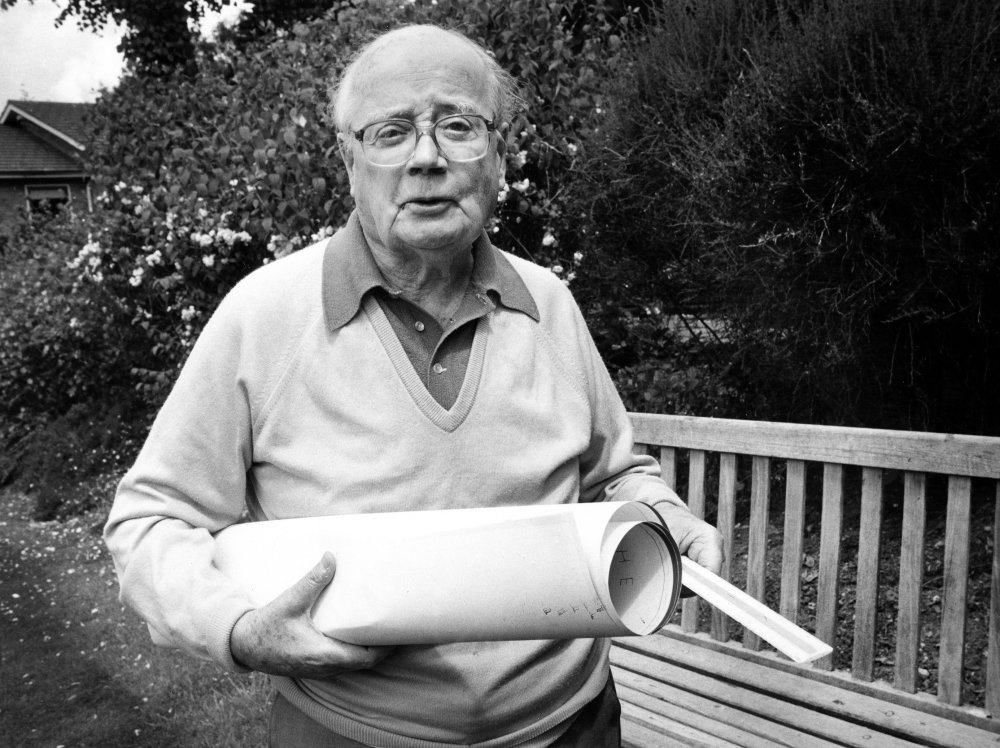

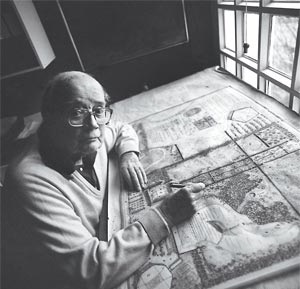

Philip Simmons’ crafting of the Star and Fish Gate in a temporary workshop set up on the Washington Mall, complete with a portable foundry and anvil, attracted a great deal of attention during the festival, and resulted in the artist gaining national attention. Among those taking an interest in Simmons’ work, and then helping bring it to a wider audience, was John Michael Vlach, a professor at George Washington University. Vlach published a biography of Simmons in 1981, which may have helped those at the National Endowment for the Arts to take note of Simmons’ lifetime of achievement in the field of blacksmithing. In 1982, the NEA awarded Simmons with a National Heritage Fellowship, the United States government’s highest honor in the folk and traditional arts. Other honors followed, including the Order of the Palmetto, his home state’s highest honor, as well as induction into the South Carolina Hall of Fame. During his lifetime, he was referred to as “a living national treasure.”

Simmons’ iron work incorporating the medical symbol of a caduceus, and a fish representing an aspect of his home region as well as the Christian faith

In spite of all of the accolades and honors he received later in life, Philip Simmons continued with humility to devote himself to his art, and to teaching younger aspirants and apprentices who wished to become proficient themselves in creating beautiful yet also functional ironwork. Despite the very significant cultural differences between his approach and those of Japanese craftspeople, I find Simmons’ approach to his life’s work characteristic of the best of what is often described as folk art, work that is appreciated for its beauty without necessarily calling attention to the artisan who made it.

Displayed below are images of a number of Simmons’ creations as a blacksmith.

A Simmons gate for St. Philip Episcopal Church, Charleston

The cover of Mary Lyons’ book for young persons, featuring Philip Simmons at work on a piece of scrolled iron

The full title of John Michael Vlach’s book, mentioned above, is: Charleston Blacksmith: The Work of Philip Simmons. The book includes a map of Charleston showing the location of Simmons’ works, as well as brief descriptions of them.