If reading this by email, please tap the title at the top to open your browser for the best experience. Then, clicking individual pictures will reveal higher resolution images.

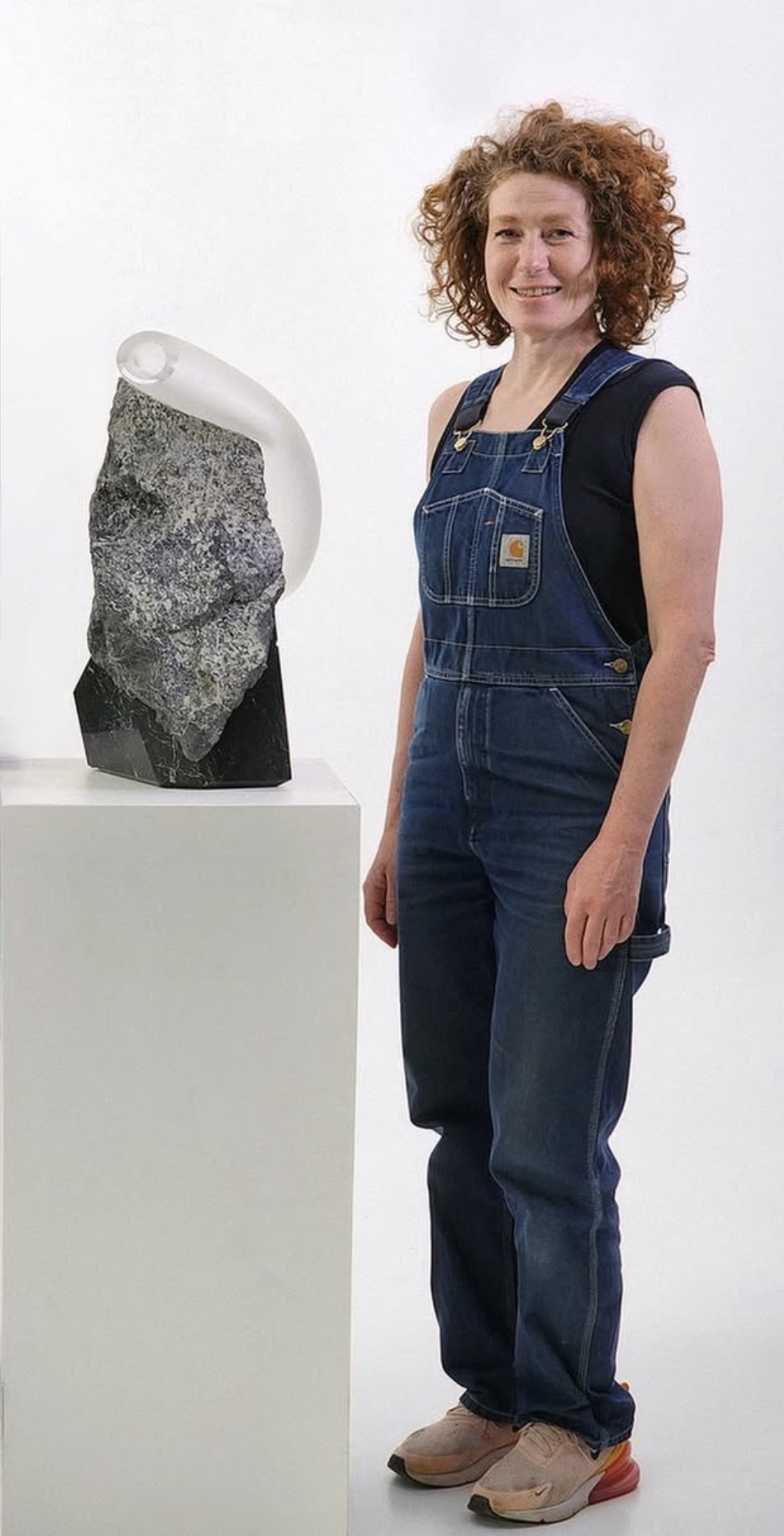

Not so long ago, my friend James brought to my attention the striking glass-based sculptural work of Laetitia Jacquetton. Born in France, Jacquetton has a background in fashion design and a longterm interest in the minimalist qualities present within much of Japanese art and its Mingei (or folk art) tradition.

When I consider what I find compelling about her sculpture, I am reminded of the art of photography. A decisive factor in effective photography, especially black and white photography, is that of contrast. This is a predominant feature in Jacquetton’s work. Though this may seem obvious, perhaps too obvious for comment, I would like briefly to explore the significance of this element of contrast, and what her work might help us to appreciate regarding other spheres within our life experience. For the sculpture of Laetitia Jacquetton may alert us to an expansive question: can dissimilar and even contrasting things – as well as ideas – be brought together into beautiful harmony? And, what might asking this tell us about our concepts of nature and grace?

Photos of Jacquetton’s sculptures help acquaint us with how contrast functions in her sculptures. For example, the photo at the top displays an intentional contrast between light and dark, as well as between shiny and matte materials.

Here, we see a contrast between translucent and opaque materials.

We also see in these photos a further contrast, between smooth and textured materials. This feature, along with those previously noted, stems from the way a fluid and malleable material has been brought into relation with a static and unyielding one. Observing this allows us to infer something about the creative process involved in the production of Jacquetton’s sculptures. The artist has taken a humanly-fashioned form and adapted it to a naturally shaped object, bringing something crafted in the studio to bear upon something found in nature.

Empirically observed contrasts like these may also have a bearing upon our ideas, and how we think about concepts like nature and grace. We may have been taught to view such ideas in terms of a perceived contrast between them, even an antithetical one. Here, when thinking about objects found in relation to others that are crafted, or about nature in relation to our view of grace, we may gain insight by considering some apposite words that Eucharistic celebrants may say before consecrating the bread: “Fruit of the earth and work of human hands, it will become for us the Bread of Life.”

Several contrasts already noted are also evident in photos of Jacquetton’s other works:

Reflecting on these photos that feature contrasts allows us to articulate what is most significant within Jacquetton’s work, her intentional juxtaposition of contrasting elements.

Jacquetton as an artisan, a human agent gifted with a creative vision and developed skills, has juxtaposed dissimilar materials, achieving aesthetically pleasing results. A singular focus upon one or more of the contrasting materials (or the qualities associated with their appearance), could lead us to highlight one aspect of the artwork at the expense of another, in an either/or way. Yet, it is the dynamic conjunction between dissimilar materials that Jacquetton prioritizes in her work. Evident contrast is accompanied by intentional conjunction, leading us to appreciate the interplay of the differences in a both-and manner.

Noticing this, I think once again of the Eucharist, which – like the Incarnation – is another and relatable example of what I am referring to as a ‘dynamic conjunction.’ For the Eucharist makes present together both the natural physical properties of bread, and the supernaturally graced properties of the sacrament.

Nevertheless, we tend to view many aspects of our world, and of our lives within it, in a simplistic and reductionist manner. For me, comparative reference to the influence of Plato and Aristotle helps limit this tendency toward reductionism.

For example, I credit Plato’s influence with an implicit encouragement to view things, and especially their moral value, in relation to a single reference point. According to this approach, something either possesses or manifests this or that quality – let us say beauty, or goodness – or it does not.

I credit to Aristotle’s influence a more nuanced approach, which nurtures a willingness to consider what we see and come to know in relation to several reference points. We are then better able to say (in a both-and way) how this or that object of attention has a particular quality, while also possessing something of a second quality, and how it can be aptly described by referring to other qualities or attributes.

In all this, I do not attribute my reflections to Laetitia Jacquetton, though her compelling sculptures have clearly inspired them.

Additional notes: Thanks to my friend, James Ruiz, for introducing me to Laetitia Jacquetton and her evocative sculptural work. / Regarding my references to Plato and Aristotle, I do not presume to have accurately summarized aspects of their thought, but rather cite what I think are aspects of their dual influences.

I hope readers might perceive how my reflective observations above are related to the paradoxical conjunctions of ideas upon which I reflected in my prior post, regarding how repentance may display beauty, and how painful grief may be accompanied by joyful reassurance.