A joy that many of us have occasion to experience – either directly or through friends and extended family – accompanies time with young children. Preschool and kindergarten teachers are by the nature of their work in the most favorable position to have this opportunity. The experience of joy we associate with time given in this way stands out for me because it is a shared joy – one shared with and inspired by those young ones who exemplify this virtue. For me, this experience has been awakened especially by my interaction with my granddaughters.

I have written previously about activities that I have enjoyed with our grandson. He shares being a grandchild of ours with six young ‘ladies’ in various stages of growing maturity. Here, I find myself musing about the wonder I have experienced with our granddaughters, who have been the source of some unique experiences for me. Having grown up with three brothers and no sisters, and having three sons and no daughters, I am encountering and learning things with my granddaughters for which I have not previously had the opportunity to experience first hand.

Among our granddaughters is one whom I like to describe as being ebullient. For she just naturally models energetic cheerfulness. She has her challenges, as we all do. But she approaches each new day’s activities with a joyfulness and positive spirit that are infectious. Though being a patient and engaging grandfather is still a growth point for me, I delight in her youthful exuberance.

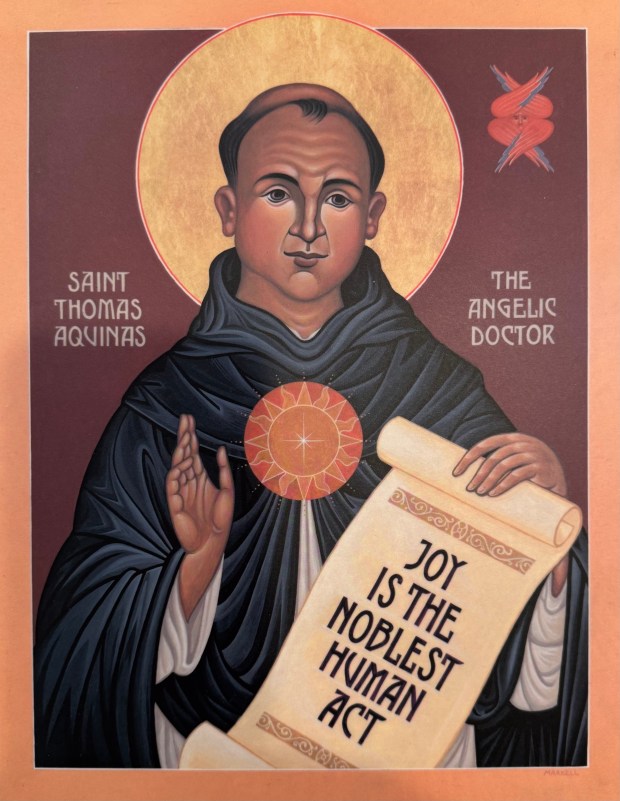

I have mentioned before an icon of St. Thomas Aquinas that I particularly value (shown above). I have seen this image attributed to Brother Robert Lentz, but now believe it is by Nicholas Markell. This icon shows Blessed Thomas holding a small plaque with the following words: “Joy is the noblest human act.”

For many of us, joy is a welcome feeling and as such we think of it as something ‘that happens to us.’ Like love and forgiveness, joy therefore is generally an experience we anticipate receiving passively, and an experience for whose value we often rely upon feelings as our guide.

The beauty of Markell’s icon, and the quotation it features, is the reminder it provides that joy is also something we choose, something we do, and not simply something that we happen to feel. We rejoice; we can choose to enjoy; and we are able to express our joy about things we encounter or experiences that we have with others.

We live in a culture that tends to distrust expressions of joy, even though most people we know – and us with them – are sadly in want of it. Perhaps it’s because we encounter so few examples of spontaneous, genuine, and selfless joy, inspired by what we see around us. Is this because there is less beauty in the world these days, or are we less prepared to perceive it? My reflection and training incline me toward the latter belief.

Joy is not one of the seven formally identified virtues taught to us by the greater Christian Tradition (among then, faith, hope, charity {or love}, prudence, justice, temperance and fortitude {or courage}). Yet, the traditional listing of virtues is not meant to exclude naming others, but rather to help us perceive their common source as well as their unity, being gifts given to us through Creation and through Redemption. Like other virtues, joy is a human capacity and a strength that we can develop through practice.

The rite for Holy Baptism in The Book of Common Prayer includes words that are prayed over candidates after they are baptized. Some of these words are particularly appropriate when thinking about the joy we often see expressed by children, but are also about something that we pray will be given to adult candidates for Baptism. In the rite, the officiant asks God to give the newly baptized persons “an inquiring and discerning heart, the courage to will and to persevere, a spirit to know and to love you, and the gift of joy and wonder in all your works.”

Here we discern a principal attribute of Beauty. In Beauty, among God’s works, we find a repository of joy and a source of wonder. For the beauty that we find in the world embodies and expresses our Father’s love for his Creation. Encountering this love brings us joy as we perceive its source and embrace him.

Today, I am thinking about the joy that each of my grandchildren encourages me to experience with them. I notice the natural joy that many children seem more able to find than do adults of my age. More readily, children delight in the world around them and in the experiences they are blessed to have. At the same time, and especially in this next phase of my life, I am reminded that joy – like Beauty, Goodness, and Truth – is not simply passively experienced. More importantly, joy is something that I want to – and can – practice.

So, with my grandchildren, I choose joy!

I close with a prayer attributed to St Francis, which speaks of joy as something we can contribute to a needy world:

Lord, make us instruments of your peace. Where there is

hatred, let us sow love; where there is injury, pardon; where

there is discord, union; where there is doubt, faith; where

there is despair, hope; where there is darkness, light; where

there is sadness, joy. Grant that we may not so much seek to

be consoled as to console; to be understood as to understand;

to be loved as to love. For it is in giving that we receive; it is

in pardoning that we are pardoned; and it is in dying that we

are born to eternal life. Amen.