We are created in God’s image and likeness. We often assume that this is reflected in the way that we think, in our capacity for reason and in our desire for wisdom. But we also reflect our creation in God’s image and likeness in our desire to love. We all want to love, and receive love. Sometimes, especially in this fallen world, we love in ways that are disordered. We love the right things in the wrong way, and we love the wrong things in what we deceive ourselves into thinking may be a good or right way.

And yet, we still love, whether it is ourselves that we love to the point of it being at the expense of loving others and the world around us, or it may be that we love others and the world at the expense of rightly loving ourselves.

The Holy Scriptures remind us that God is love. And that God first loved us before we knew it. And that God so loved the world that he gifted himself in the form of the Word made flesh, who came among us, full of the grace and truth that he has so generously shared with us. “I am who I am” (what God spoke to Moses from the burning bush) becomes the source of “we are who we are,” especially when we become aware of and live into the fullness of who we really are.

And so, to love what God loves is to share in the experience of God’s love. Awareness of this leads us to become more aware of the way we are called to share in God’s own way of loving. To do so actually comes to us naturally, even though we in our fallen state are impaired in our ability fully to live into this reality, and believe we are capable of it.

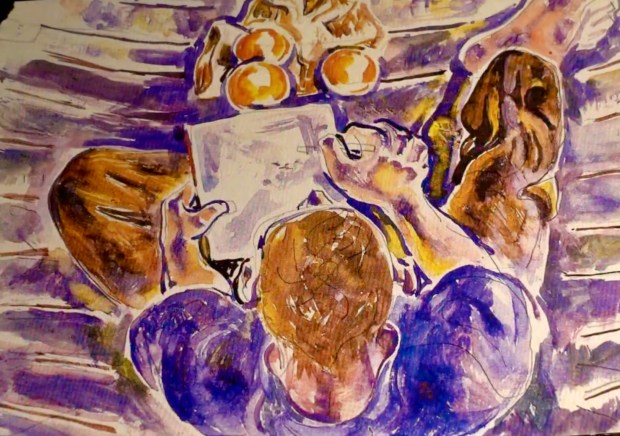

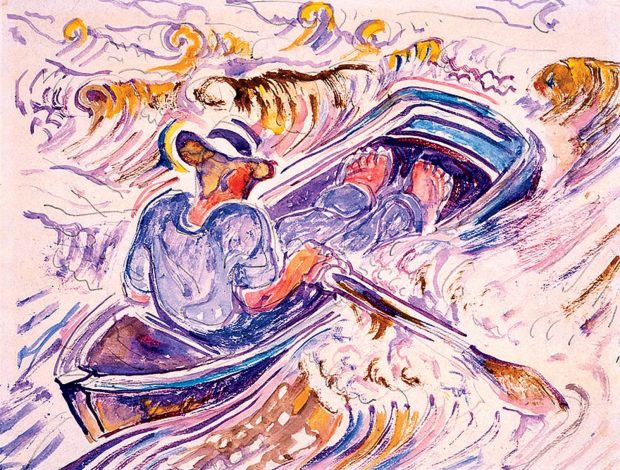

In my prior post, I reflected on how some of this capacity to love what God loves may be revealed in the life and work of Walter Inglis Anderson, who himself may not have been aware of the fact, nor may have had the conscious ability to believe it. In this respect, Anderson, followed in the spiritual footsteps of John Muir, whose earlier example may help us appreciate this dimension of the Mississippi painter’s relationship with nature. For Muir, through his childhood formation in orthodox Reformed Christian beliefs, came to believe he was loving Creation as God loves it, however much Muir’s vision expanded and broadened over the years so as to appear that he had moved beyond the bounds of traditional faith.

To experience joy when we encounter and perceive the beauty we find in the world – even in ourselves – is to experience God’s love for the world. Beauty in the world is a manifestation of God’s self-giving, and of a love that is self-giving, even to the point where we are capable of bringing harm to it or rejecting it. The same is true for God’s love for us, and for those with whom we have been given the opportunity for fellowship and community. For God’s love is not for us solely, as individuals, but is present in fellowship and in community, especially in communities founded upon this great gift of divine love.

Here, we can come to appreciate another insight we can gain from learning about Walter Inglis Anderson. Like the earlier Muir, Anderson came to perceive – or perhaps always intuitively knew – that to see, to really see what is in and around us, is enabled by ‘getting out of the way.’ When I, as one who sees, am conscious and then distracted by my awareness of my process of seeing and perceiving, I become absorbed with my own subjectivity, at the expense of more fully becoming focused upon the objects of my perception. In seeking to love you, or things in the world around us, my focus upon my process of loving or seeking to love impedes my actual participation in really loving you, you who are a fellow subject of loving and not simply an object of my love.

I think that Anderson was enabled to arrive at such an awareness by enacting his desire to be among and really see the plants, birds, animals, the seashore, and the changing weather conditions, while on his solitary sojourns to Horn Island. Therein lies the paradox. God’s love for the divine beauty reflected in the world that he has made was at the heart of Anderson’s love for the beauty that we find in nature. And in sharing in that same love of beauty, he came to perceive how he was actually not alone, even in his periodic states of hermitage under the shelter of his upturned dinghy.

Awareness of this is one doorway into perceiving and then enjoying what Jesus spoke of when he said, “Wherever two or three of you are gathered, I am there.” The great “I am” is with us, now to behold and embrace, Spirit in Flesh, Word made human, not only in ourselves and in the things around us, but also between us at the heart of our fellowship.