Jim Janknegt: I will make all things new (2005)

The title of this post comes from Charles Wesley’s hymn-text adaptation of words from Revelation that refer to the Second Coming of Christ in glory: “Behold, he is coming with the clouds, and every eye will see him, even those who pierced him, and all tribes of the earth will wail on account of him” (Rev 1:7). In this first week of Advent, and perhaps having sung Wesley’s hymn on Sunday, we need to explore what this ‘wailing’ may involve.

Many people today regard the Second Coming as something prompting fear about a Final Judgment. This may be one cause for the wailing that Wesley anticipates. Though texts in Revelation, as well as in the Gospels, certainly involve this theme, Revelation’s author is also very clear in expressing a faith that Christ’s return will involve restoration, the fulfillment of promises, and the beauty of shared glory. Hence, the wailing may also reflect holy sorrow stemming from a deepened awareness of personal sin, accompanied by ‘tears of joy’ over being forgiven.

Wesley’s verse 2 of his hymn predicts the first dimension of wailing: “Every eye shall now behold him, robed in dreadful majesty; those who set at nought and sold him, pierced, and nailed him to the tree, deeply wailing, … shall the true Messiah see.” Verse 3 describes the second dimension: “Those dear tokens of his passion still his dazzling body bears, cause of endless exultation to his ransomed worshipers; with what rapture, … gaze we on those glorious scars!”

Words in Revelation, preceding and following its prediction about how “all tribes of the earth will wail,” provide a foundation for hope. The author says at the beginning of this last book of the Bible (1:4-5), “Grace to you and peace from him who is and who was and who is to come, and from … Jesus Christ the faithful witness, the firstborn of the dead…” And then (in 1:8) we find, “‘I am the Alpha and the Omega,’ says the Lord God, ‘who is and who was and who is to come…’”

These words are echoed near the end of Revelation, where we find a description of the New Jerusalem and a renewed Creation. Among them are these: “And he who was seated on the throne said, ‘Behold, I am making all things new'” (21:5).

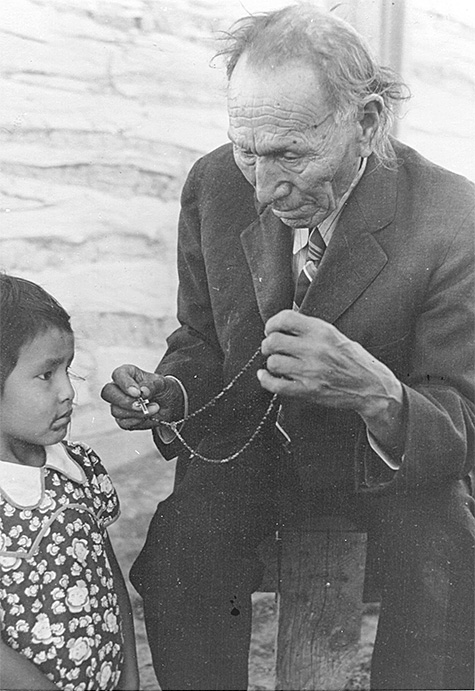

Jim Jaknegt’s painting, I will make all things new, expressively captures the positive dimension of these themes and the ground for hope that lies in the beauty of the Lord’s return. All things! That is a phrase worth exploring in terms of quite a number of biblical texts, especially Paul’s letter to the Colossians.

In the first chapter, Paul writes, “For by him all things were created, in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or authorities—all things were created through him and for him. And he is before all things, and in him all things hold together” (1:16-17). Paul then indicates (1:19-20) the ground for hope regarding “all things,” which Janknect suggestively depicts: “For in him all the fullness of God was pleased to dwell, and through him to reconcile to himself all things, whether on earth or in heaven…” God’s ultimate goal in all this is reconciliation rather than condemnation, even though people who dismiss God’s ongoing work of reconciliation may find themselves brought to sadness.

Notice the pronounced swirling motion in Janknegt’s painting, as all things are caught up into the returned Lord’s orbit. But all people? For unlike flora and fauna, as well as inanimate objects, human beings made in God’s image and likeness possess the freedom of will either to accept or to refuse God’s initiatives to reconcile us into divine intimacy. This is why there may be at least two dimensions to the wailing that the Lord’s return is likely to initiate. For grief over sin may bear fruit in repentance.

We should therefore note the words of invitation at the end of Revelation: “‘Surely I am coming soon.’ Amen. Come, Lord Jesus!” (Rev 22:20)

Jim Janknegt is a painter who is based in the Austin, Texas, area, who has produced a remarkably large body of work based on biblical themes and imagery. The website featuring his work can be found at http://bcartfarm.com/ I have admired, and with his permission have featured, his images for many years. Lo! He comes with clouds descending appears as Hymn 57 in The Episcopal Church’s The Hymnal 1982.