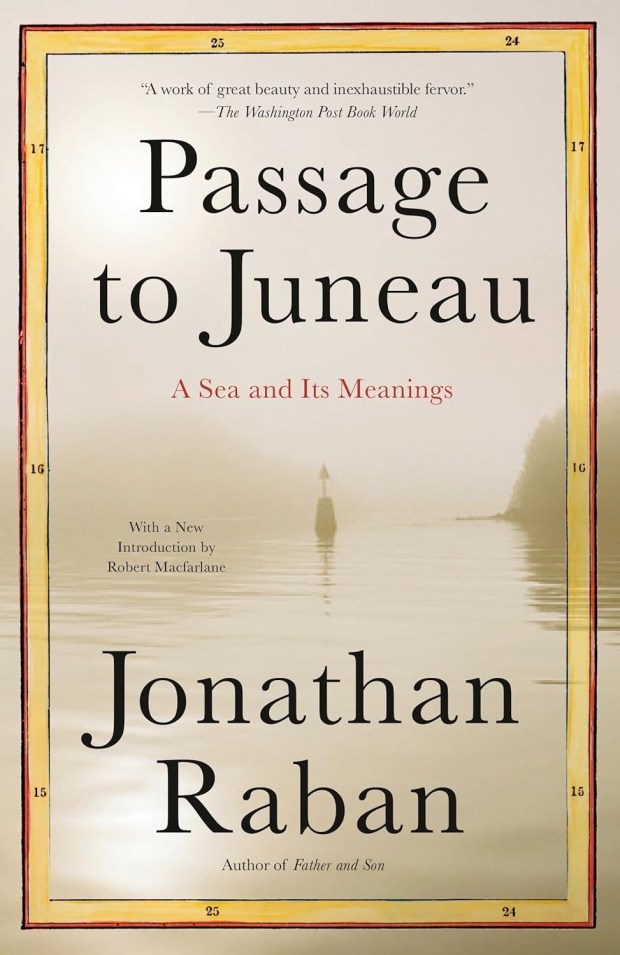

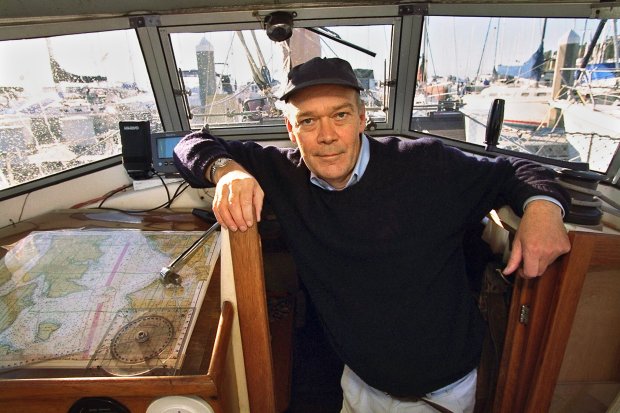

I find that authors who are effective at reading aloud their own writing offer an extra dimension of insight regarding their work. Jonathan Raban’s recording of A Passage to Juneau, is an example to which I like to return. Being a sailor myself, I find voyages, sailboat cruising, and basic navigation provide more compelling metaphors for how we think of our course through life than the often used one of journeying. Raban’s book about sailing his 35′ Swedish-built ketch from Seattle north to the capital of Alaska recounts so much more than a trip up the Inside Passage through the interior waters of British Columbia. His reflective narrative allows us to witness – through his eyes – how he faces the challenges associated with the death of his father, an English Vicar, as well as the coming apart of his marriage while he remains close to his young daughter.

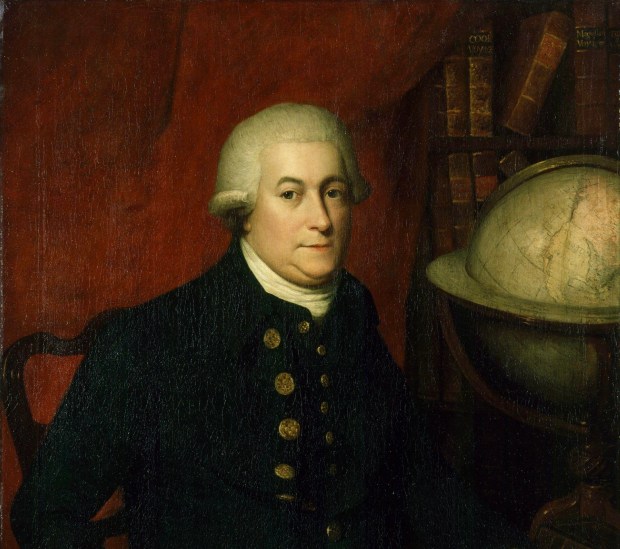

Raban includes as a literary companion, on what unfolds as an imaginatively-shared voyage, the technically gifted but personally flawed explorer, George Vancouver, through the latter’s ships logs and historical biography. Raban’s log of his passage in the Penelope is interspersed with perceptive observations about his family off in England and down in Seattle, while also sharing reflective thoughts regarding Vancouver’s own earlier exploration of the same waters. So there are three interwoven strands within the writer’s expressive narrative, Raban’s cruise, his interior journey through memories and toward an uncertain future, and a travel oriented book that shares his evocative impressions of the waters and terrain of Puget Sound and the Straight of Georgia that is mixed with those Vancouver.

Having lived on Vashon Island while commuting to college on the Washington State ferries, I remain drawn to some of the same locations in Puget Sound that play an early role in the book. The immediacy of the author’s description of the area in and around Seattle’s Fishermen’s Terminal where he prepared for setting off, as well as of the beautiful San Juan Islands, provide a very good sense of what he was leaving behind on his travels, while also emotionally carrying aspects associated with those places with him as he ventured into less familiar waters.

Raban was nothing like an enthusiastic newcomer to sailing when embarking upon his “Passage.” His other voyaging books, particularly his account of his circumnavigation of his native United Kingdom (Coasting), as well as his editorship of The Oxford Book of the Sea, attest to his deep knowledge of sailing and all things nautical. His attraction to such voyages is also reflected in his highly readable account of his water journey down the Mississippi (Old Glory), from St Paul to New Orleans, and was the fulfillment of a childhood fascination with the Great River and its history .

The Audible recording of a condensed version of Passage to Juneau nicely captures Raban’s resonant voice and British vocal style. Portions of his recording give a good sense of the author’s subtle humor, accentuated by his sharp eye for memorable detail. Imagining how Vancouver’s voice must have sounded to his shipmates, Raban reads passages from the explorer’s diary with a slightly exaggerated flat nasal intonation, imbuing the historical figure with a fuller sense for us of the 18th century navigator’s complicated humanity. And Raban’s description of his brief interaction with officious Canadian Customs inspectors regarding a suspect American potato, found during a search of his boat, provides a memorable anecdote. Both examples and others like them function, I think, as thoughtful counterpoints to the more difficult aspects of Raban’s ‘interior passage,’ a journey through reflections prompted by the loss of a parent and the diminishment of a marriage.

The Audible version of a cover for Raban’s book, Old Glory

One key to appreciating Jonathan Raban’s, Passage to Juneau: A Sea and its Meanings, lies in its subtitle. Clearly the author has written something more than an absorbing description of a nautical adventure, though he certainly provides that. The interest of this book for me lies in its implicit invitation to reflect on what draws some of us to the sea, to find our way on waters that may have patterns but no directional lines or unnecessary limits. For the sea is where what is called ‘human geography’ and our created pathways may diverge from the given features of the natural world.

As is broadly true with much of our life on land, a parallel to navigation over the water exists with how we make our way forward in our decisions and actions, day by day. This is the parallel we can perceive between sailing and what is formally called casuistry in moral theology. All of us, in all circumstances, are challenged to apply universal principles or rules of thumb to the ideosyncracies of everyday situations. Generic and abiding principles (with boats, it is things like Coast Guard rules and the observed behavior of tides), coupled with familiar tools (a compass, wind direction finder, charts, etc.), need to be brought into engagement with particular circumstances (the wind, waves, and tides, as we find them today). Through this process we discern with greater clarity location and direction, especially when our efforts are coupled with a grasp of purpose. Otherwise, and in more ways than one, knowing where we are and where we are headed can be difficult.