If reading this by email, please tap the title at the top to open your browser for the best experience. Then, clicking individual pictures will reveal higher resolution images.

Those who watched the Winter Olympics broadcast from Nagano, Japan, may have gained some familiarity with a region sometimes referred to as the Japanese Alps. While living in Japan, my parents developed a deep interest in Japanese folk art (Mingei). Through this, they became acquainted with Sanshiro Ikeda, a recognized authority on Mingei, who built craft furniture. Through our trips to Nagano-ken (or prefecture), we visited Ikeda’s small furniture factory and the country farm house he had restored, and in which he lived. Through these visits, we became familiar with Matsumoto, its beautiful many hundred year old castle, and the surrounding Nagano countryside. My strongest memory, though, is of Ikeda’s restored traditional farmhouse, and those like it in the area.

The choice of Nagano prefecture as a location for the Winter Olympics was based on the fact that that region regularly receives a good deal of snow. As a consequence, the historic pattern for the design of farm and country houses involves very steep roofs which are quite often thatched. The combination of these two characteristics in the resulting roofs renders them amenable to heavy snow loads, which also help provide additional insulation against the seasonal cold weather.

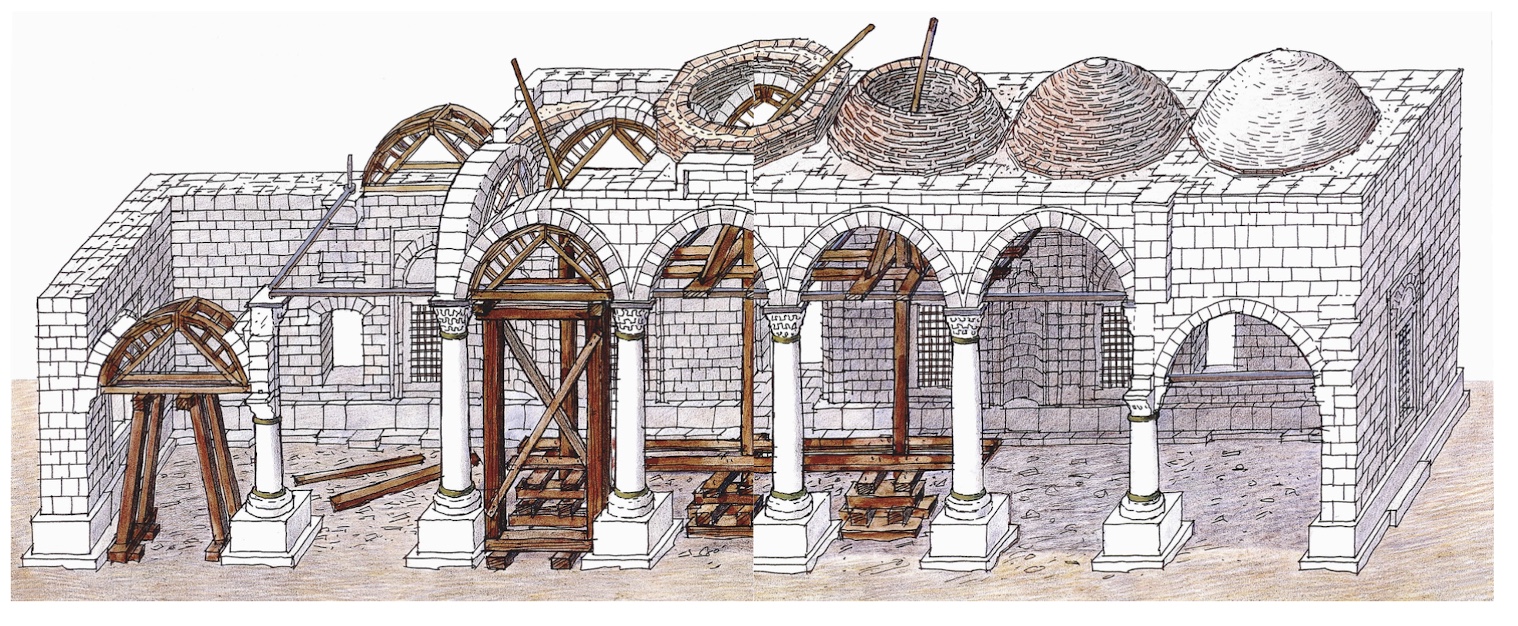

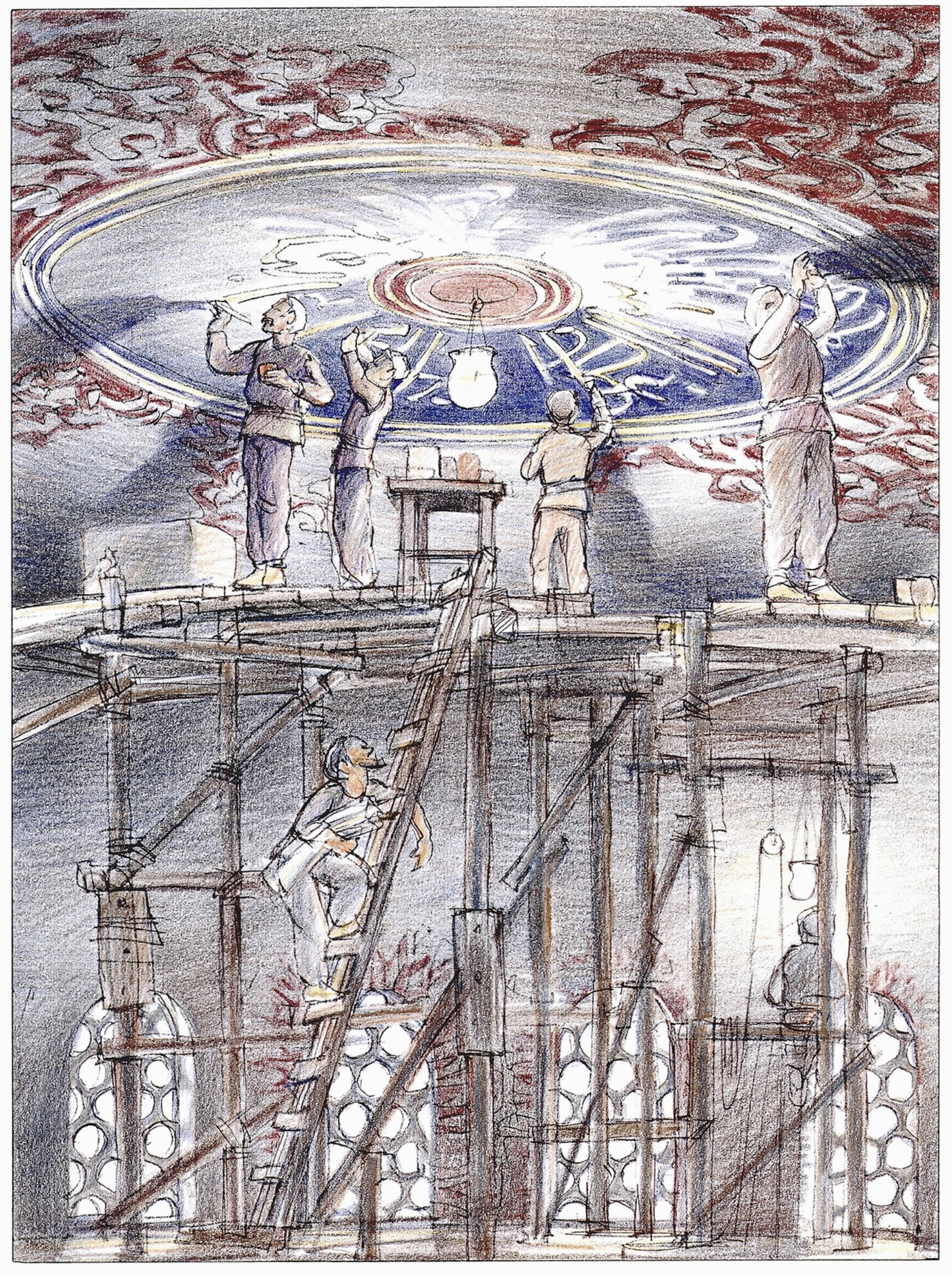

These farm and country houses are typically built from wooden posts and beams, with plaster or stucco walls, and wooden plank floors if not otherwise covered with tatami mats made of straw and rice husks. The equivalent of what we refer to as rafters, and the lath cross pieces or straps supporting the thatched roof material, are typically beams made from tree branches or thick and thin pieces of bamboo, lashed together with rope, something that surely would not pass building codes for contemporary construction.

Traditional house with beams lashed together (above) and stucco walls above sliding shoji (lattice door and window panels), seen in the lower photo.

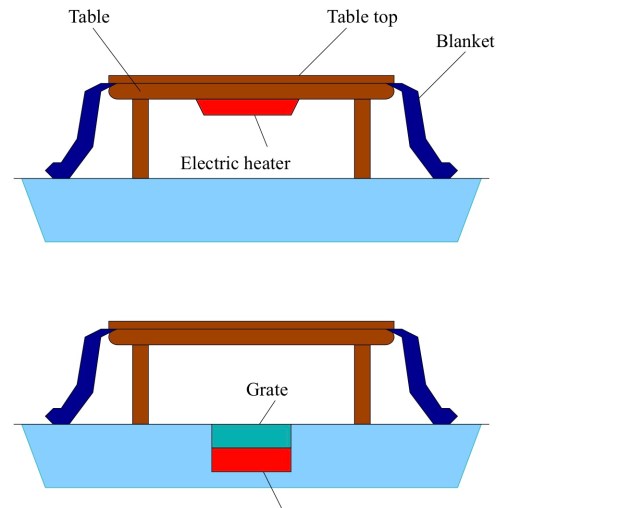

Instead of any form of central heating, generally unknown in Japan until modern times, many of the rooms on the ground floor would have a footwell in the floor, at the base of which traditionally there would have been a small charcoal brazier (charcoal kotatsu). Those in the room sitting on the floor, with their legs dangling in the footwell, managed to stay warm with the benefit of a small table over their thighs and knees, above the footwell, along with a lap blanket suspended from the low table.

A kotatsu blanket (with table top removed)

Kotatsu design (traditional charcoal and contemporary electronic patterns)

A similar but very shallow well-like indentation in the floor provided a place for cooking at the floor level.

Quite often these houses would feature one or two successively smaller floors above the ground floor in a way that will recall Western A-frame ski lodge houses. Typically, the sleeping areas would be on the upper floors with futon beds laid out on the tatami mats, thick quilts provided, and pillows stuffed with uncooked rice grains.

Interior of a traditional farmhouse showing a futon (or Japanese mattress), and a quilt covering, set above tatami mats.

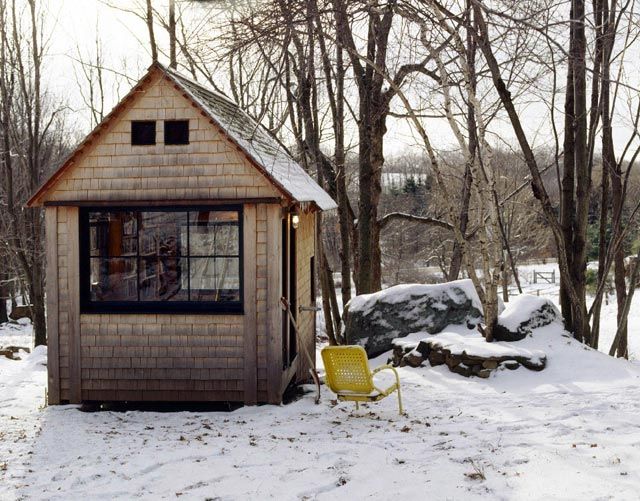

Below, I am including a selection of photos of various examples of traditional Japanese country houses and related buildings, which demonstrate the consistency with which this approach to domestic architecture was adopted and practiced through the centuries. The first three photos show what appear to be contemporary structures built in the historic farmhouse style (followed by photos of historic structures).

The following photos feature historic structures.

The same village area (as in the photo above it) on a winter’s evening

The well-preserved historic examples of Japanese farm and country houses in the photos above, as well as the contemporary reproductions employing this historically-informed approach to domestic architecture, attest to the heightened appreciation that Japanese people have for their ancient culture. It may be that, as in some other parts of the world, the highly advanced technological developments characterizing the urban areas where most of their people now live, has nurtured a deep and latent regard for aspects of their nation’s social, artistic, and spiritual heritage.