I have long been captivated by some words offered in our Prayer Book for the newly baptized, that they might receive the gift of joy and wonder in all of God’s works. These 12 Days of Christmas are surely the time of the year when hopes for joy and wonder are most honored by people all over the world.

While we focus on the gift of the long-promised Prince of Peace, and Wonderful Counselor, we also engage in what we might think of as a widespread indulgence in sentimentality. Our celebration of the Promised One can become overwhelmed by the secular accoutrements of ‘the season,’ with various permutations of the legacy of St Nicholas of Myra morphed into an attractive mythic figure we call Santa Claus, or Father Christmas as folks in the U.K. like to call him. His popular name in America, diminutively reduced to Santa or Saint Nick, masks the religious history of his churchly origins as a figure numbered among those on the Calendar and in the Lectionary. Elves in Santa’s fabled workshop take the place of saints and un-named believers whose works of faith are not remembered with specifics, while the lore of the mythic figure who comes to visit children’s’ homes with gifts occupies public attention.

Among others who have led parish church congregations, I have done my share of encouraging observance of a traditional Advent, stressing the significance of St Nicholas’ feast day (December 6), and urging retention of Advent hymns and restraint in home and church decorations characteristic of our culture’s ways of anticipating Christmas. For me and others, the 12 Days of Christmas would be our time of celebrating our Lord’s Nativity by lighting trees, sharing gifts, and treating ourselves to special foods, right through the feast days of St Stephen, St. John, Holy Innocents, and The Holy Name, to Twelfth Night and a proper regard for the Magi’s visit on the Epiphany, January 6. Preferring such an emphasis has caused some of us to appear to be in quiet conflict with the patterns of our wider culture. For the world around us has more and more begun its anticipation of Christmas by playing ‘music of the season’ early in November, long before Thanksgiving, while also decorating homes and public spaces with Christmas-related lights, poinsettia, and objects related to our enjoyment of gift-giving and receiving. At the heart of all these outward signs of anticipation is our longing for a recovery and enjoyment of what we celebrate as ‘the most wonderful time of the year.’

My adult children like to gently rib me that I have ‘gone soft’ on Advent. And that I have slowly succumbed to the influence of ‘secular culture’ upon what I think should properly be seen as a religious holiday – as if the two emphases are in some way counterposed, and in tension. With my predilection for retaining our Anglican heritage’s rightly attributed but oft-caricatured principle of taking a “both-and” approach to many aspects of our faith and beliefs, I prefer to think that I have broadened my outlook in my search for forms of a deeper synthesis that lies within ‘reality.’ Perhaps these changes in me are due to having grandchildren who live nearby. Yet, as I remember Oliver O’Donovan encouraging us to perceive, compromise is not always ‘of the Truth,’ but can also be ‘in relation to the Truth.’

Hence, my continued fascination with joy and wonder. Joy and wonder might be two of the best words to describe what we think of, and may remember as, a child’s view of what Christmas is all about. And if there is any substance to the perception that our transition from childhood through adolescence to adulthood is often marked by our loss of genuine engagement in imagination, fantasy, and therefore with wonder, it is surely reflected in our thinking that Christmas is primarily significant for children. And therefore something that we enjoy cheerfully when we participate in social occasions where we temporarily suspend our disbelief in fantasy for the sake of the merriment we can enjoy with others.

All this has deeper significance. What if the world we live in is truly animated by the Holy Spirit, thoroughly infused with divine Grace and Wisdom, and permeated by a wellspring of joy that is godly? What if our culture’s pattern of anticipating and celebrating Christmas is an example of what Jesus had in mind when he encouraged his adult listeners to become like the children he embraced and held up as an example of Kingdom-participation and life?

As when he placed a child in the midst of them, and said, “Truly, … unless you turn and become like children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven. Whoever humbles himself like this child is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven.” Has it occurred to us that he may have been speaking first about himself (He who humbled himself to become an infant and then a child)?

Childish and child-like are, of course, not necessarily the same. And by distinguishing the terms, we may begin to recover something. That we don’t necessarily need to pare down features of our cultural approach to Christmas to get our celebration back to being something Jesus might want us to enjoy. But that we could also see our patterns of Christmas celebration as involving the kinds of gatherings and events at which he would have enjoyed himself, identifying with our delight in such moments, and where he would encourage us to embody his spirit of discernment of how God is present and at work in all that is around us.

It is all about him. And he is all about us.

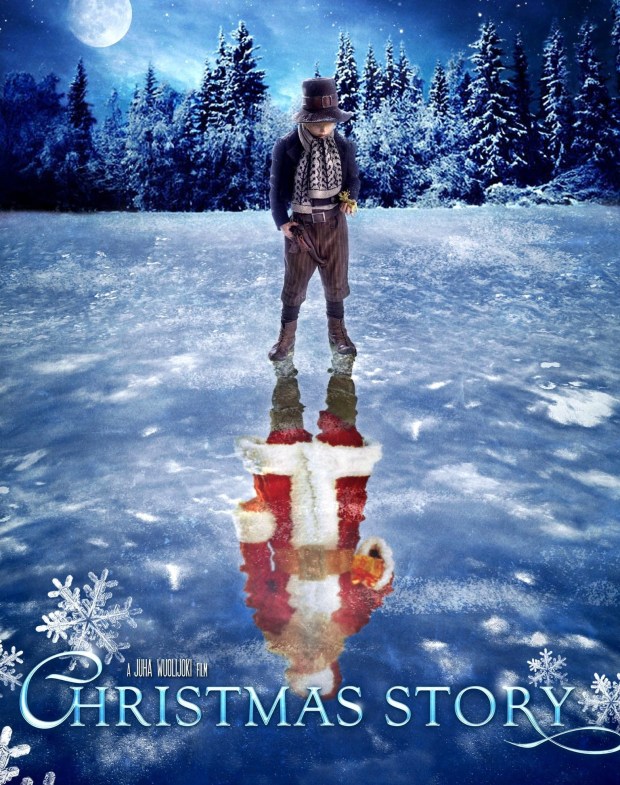

Note: the quoted words of Jesus, above, are from Matthew 18:2-4. Christmas Story (filmed in Finland/Lapland, and A Boy Called Christmas are movies currently streaming.