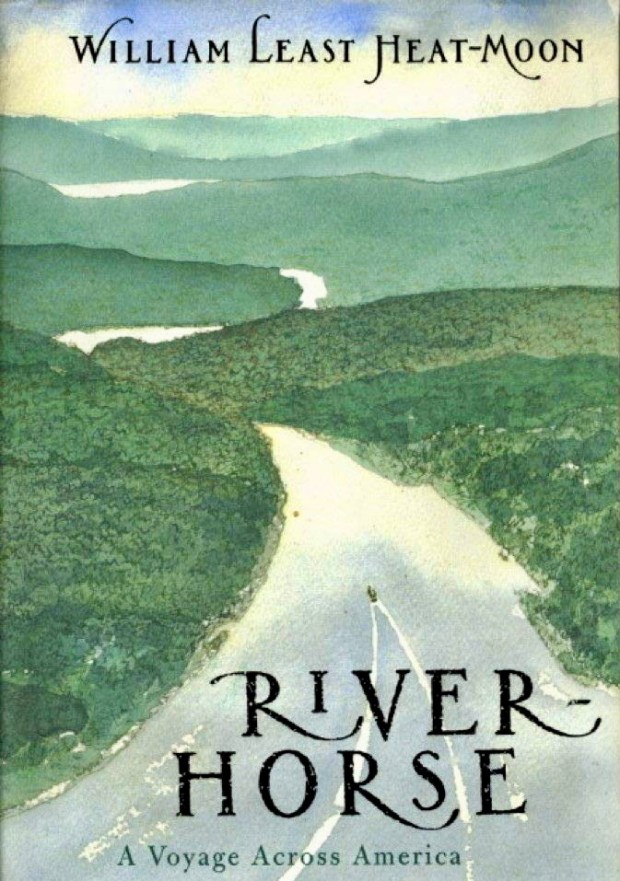

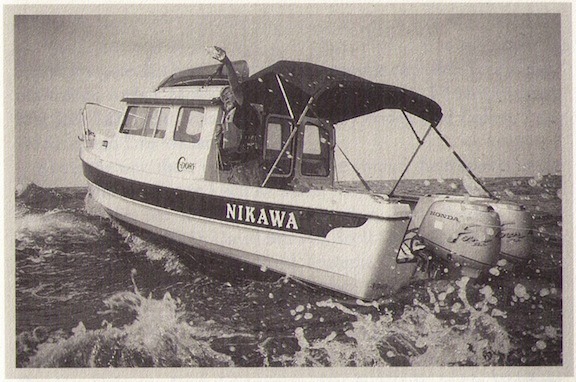

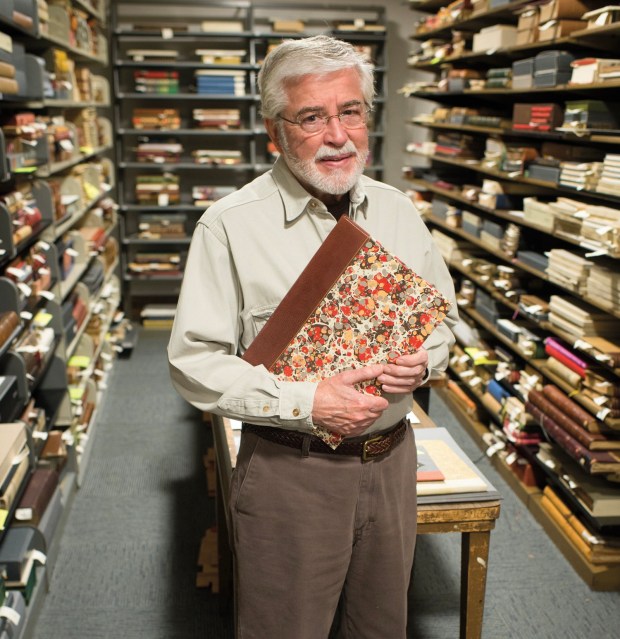

William Least Heat-Moon (the pen name for William Lewis Trogdon, hereafter WLHM), continues to impress me with his nuanced vision of the United States. He consistently offers his readers a synthesis of well-crafted writing, an appreciation for the sometimes hidden beauty of the lands and waters he explores, and a sensitivity to features of our common humanity latent within the historical events attendant to the people and places he visits. I return from time to time to his book, River Horse: A Voyage Across America, a book I love for its clear-eyed record of his water-based journey across this country. On a 26’ C-Dory motor cruiser, and accompanied by several friends whose roles are represented by symbolic monickers (e.g., Pilotis, and ‘the Photographer’), he traces a voyage from the mouth of New York Harbor to that of the Columbia River in Oregon. Readers familiar with geography but new to this book will wonder how WLHM managed to cross the Continental Divide in the C-Dory, and will discover that the author and his friends’ passage was facilitated by a vehicle trailer around some portage points, and by a canoe through and over the western mountains at their highest points.

WLHM periodically uses unfamiliar vocabulary in a way that may strike some readers as pretentious, but which I generally find apt and instructive. Clearly, he savors words as much as the sights he seeks to capture through his writing. His evident identification with the sentiments expressed in quotations from earlier journals and public documents, and the care with which he treats them regarding the places he visits, tells us a lot about the author.

This is the kind of book that boaters who have a yen for nautical adventure will love. As I do for his other published work, I have a high regard for what WLHM has accomplished with this travel narrative. He has filled it with insight concerning not only geographical terrain, but also with pertinent observations about the people he meets, who interact with or are sometimes indifferent to the beauty he encounters along his passage. As an able and informed observer, the author communicates much about what he sees as well as about its potential significance for others who might come along after him. His book is shaped by his dialogue with the recorded experience of those who have traversed the same waterways and their surroundings before him, as well as by contemporaries familiar with the same areas. By this means, WLHM draws readers in to his own reflective experience. He invites us ‘to look over his shoulder’ and then journey with him through the captivating but also sometimes less than encouraging features of where he goes. To this point, in his expressed appreciation for numerous rivers negotiated by Nikawa, he does not overlook reporting on the accumulated plastic debris that by the mid 1990’s had already collected in certain pockets of at least one river. He then offers brief but also judicious comments with respect to potential remedies for public attitudes about the waters that border our towns and rural lands.

Aside from his absorbing description of the commencement of his voyage, which effectively draws the reader into his narrative, several passages in the book linger in my memory. I think of his account of Nikawa’s passage down the relatively gentle Ohio River, which is often calm due to the series of locks and dams. His reflections about the river evoked thoughts of a possible retracing of his pathway through those waters, especially given their occasionally curious personal and historical associations (as in the following vignette).

In this part of his text, WLHM offers a brief account of an Irishman who was persuaded by Aaron Burr to join a nascent conspiracy to found a new and independent political domain lower down the Ohio and by the Mississippi, a venture later halted by authorities sent under the direction of Thomas Jefferson. This provides a good example of the numerous occasions about which WLHM interweaves observant travelogue with his study of past events. Interspersed within this same portion of the narrative focused on the area around Marietta, the author reports humorous offhand comments gleaned at a diner. After his conversation with a local woman, a beautician named “Enna-mel,” she leaves him with a parting remark that adds spice to the story.

Shaping words about the work of an accomplished writer can be hazardous, though I am encouraged by WLHM’s quotation of a portion of William Clark’s Journal from the great 1804-6 expedition to the West. Clark’s struggle to portray the then sublime splendor of the untamed Great Falls of the Missouri River clearly were significant to WLHM. This is evident in the latter writer’s implied recognition of the challenge posed by his own desire to communicate the fullness of his experience of the same waters.

River Horse is sprinkled with anecdotes from earlier times, along with perceptive observations from William Least Heat-Moon’s journey notes. He well-describes the many rivers through which Nikawa made her way, and almost every page of this book offers detailed insights that will reward an attentive reader, especially those who muse – as I have – about undertaking a similar adventure.