If reading this by email, please tap the title at the top to open your browser for the best experience. Then, clicking individual pictures will reveal higher resolution images.

Recently I became reacquainted with a book I discovered some years ago, by an author whose work I greatly admire – David Macaulay. It is his book on Islamic mosque architecture, based on a historically informed but fictional mosque erected in Istanbul in the 16th century. Macaulay’s great skill lies in his ability to provide the reader with insights gained from his use of drawing with pen and ink, frequently with color overlaid, in such a way as to unfold the often complex inner structure of the buildings he wishes to explore and explain. For a primer on traditional mosque design and construction, complete with a glossary of terms, the book is invaluable.

The project featured in this book is a mosque commissioned by Suha Mehmet Pasa, a fictitious high official in the early Ottoman period who engages in a charitable act inspired by his Islamic faith and the five pillars of Islam (faith, prayer, charity, fasting, and pilgrimage). He funds the design and construction of a complex of buildings that includes both a grand mosque and its accompanying courtyard and related structures, as well as a mausoleum for himself upon his death. The influence of the historical architect, Mirmar Sinan, as well as Sinan’s breathtaking Süleymaniye Mosque in Istanbul (depicted below), are plainly evident in Macaulay’s composition of the book.

Because of my own fascination with domes incorporated within mosque architecture, I will focus here on that aspect of Macaulay’s book, though he provides a comprehensive account of the construction of almost every feature of a traditional mosque from the early Ottoman period. I find most helpful the following diagrammatic illustration of the basic building components which together support the dome on such a mosque as the Süleymaniye Mosque, featured in a prior post.

The above illustration corresponds to the following floor plan for the same hypothetical structure.

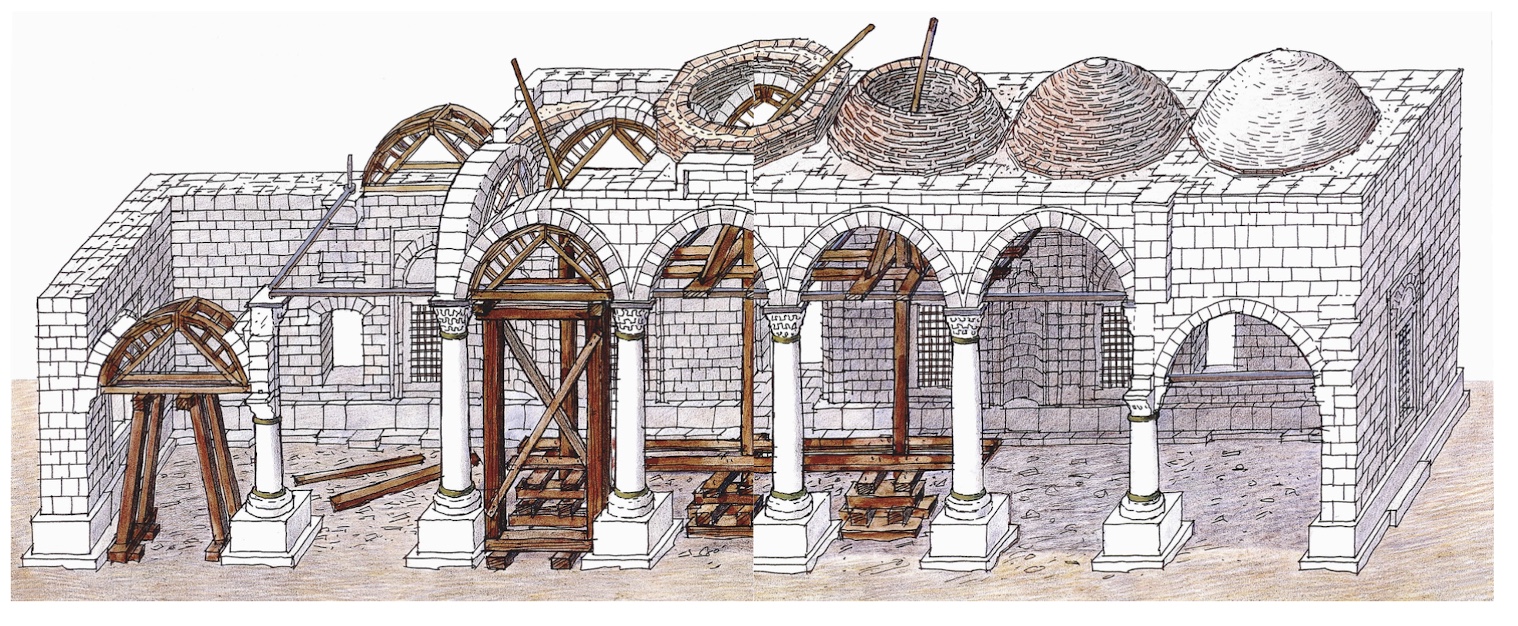

Now, how did that imaginary 16th century architect, his masons and carpenters, manage to build the magnificent dome featured in this project, and as we find in the actual Süleymaniye Mosque? Macaulay unfolds the mystery with a series of instructive drawings that give us insight into the process. Once the proper height of the walls and support piers was attained, a semi-circular structure of wood was constructed to provide the proper curvature of the intended dome (as seen below).

This structure was then lifted up and placed upon a kind of spindle, so that it could revolve horizontally around the perimeter of what would become the brick structure of the dome.

With the rotation of this semi-circular wooden form, the builders could stack up the bricks according to the intended proper curvature of the inside of the dome, while allowing the exterior of the dome to be wider at its base, for greater strength and stability.

A final step in the construction of the main and other domes was the preparation of sheets of lead, cut in precise patterns so that they would sheath the dome with a series of overlapping panels, to avoid water intrusion:

The smaller domes covering areas of the courtyard and entrance portico were constructed in a similar fashion, but on a smaller scale, as seen in the following illustrations. A simple swinging pendulum-like wooden arm was employed rather than the more elaborate semi-circular structure used for the large main dome.

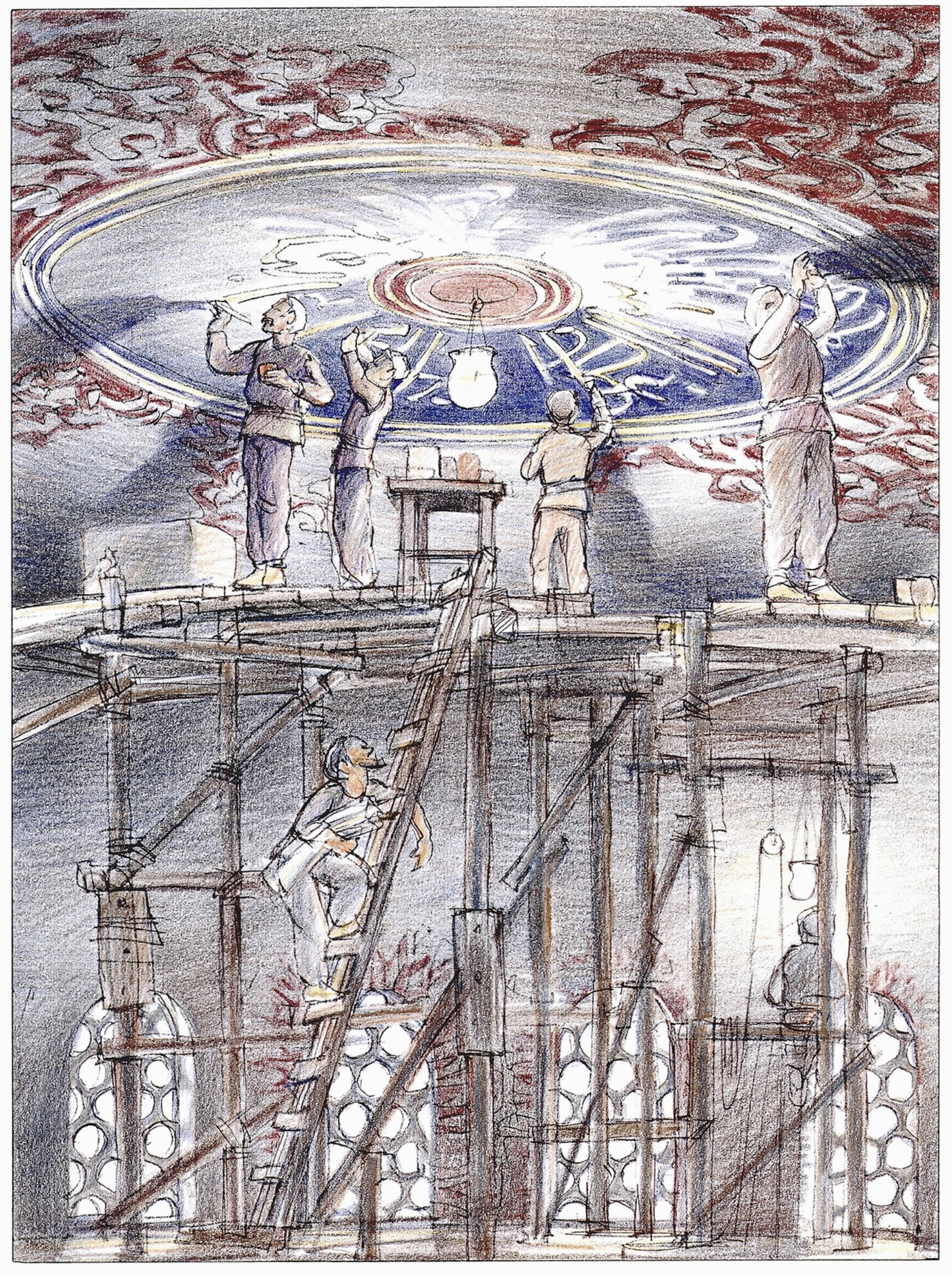

Completion of the construction of the main dome was followed by the finishing of the interior surfaces with plaster, and then with elaborate paint work, which of course involved the need for scaffolding and platforms.

Macaulay then provides two evocative interior views of the finished interior of the mosque, and from two unique perspectives.

These drawings and my primary focus upon the dome aspect of this hypothetical mosque project provide just a hint of the richness to be found in this evocative book. Though it may appear to be a ‘picture book’ intended for middle school students, it is actually a rich source of information for adults who wish to become familiar with the basic elements of historical mosque architecture, and the construction methods used to produce such buildings in the early Ottoman period. In addition to the highly instructive drawings, the glossary at the back of the book is also of significant value.

As readers might guess, I highly commend this book.