[If reading this by email, please tap the title at the top to open your browser for the best experience. Then, clicking individual pictures will reveal higher resolution images.]

The Nitobe Memorial Garden on the grounds of the University of British Columbia (UBC) is readily recognizable as a traditional Japanese garden. Like other gardens of this type, it provides an experience of tranquility. Even in an urban area such as Vancouver, Nitobe Garden offers a quiet refuge from daily life concerns and tensions that visitors might carry with them.

An interpretive guide to “understanding Japanese Gardens,” found on the UBC Botanical Garden website, asserts the following:

… it is almost impossible to clearly state what defines a Japanese garden. Many Japanese resist classifying and categorizing the various features of Japanese gardens.

The website attributes this reluctance to the idea that beauty “not explained allows the viewer to remain in a state of wonder.” This worthy observation applies as much to modern abstract painting as it does to historic patterns of landscape arrangement. Yet, in this and in the next post, I will articulate characteristics that enable us to distinguish a traditional Japanese garden from, for example, a casual English cottage garden or a formal French garden.

The UBC website acknowledges how “most visitors can tell when they have entered a garden created and maintained in the Japanese tradition,” crediting this perception to people who “are sensing the Japanese spirit that informs these spaces.” This may be due to how various strands within Japan’s cultural history have coalesced to form a recognizable ‘style’ manifest in its gardens. Among the results of such a melding process, we can identify and describe several features in the Nitobe Garden that are common to other well-known Japanese gardens.

We can begin by observing how gardens and parks found in the East and in the West have a number of shared attributes. Among them, most gardens and parks around the world feature a scheme for the arrangement of their various parts even if it is not readily evident to visitors. Many such places appear to promote and preserve a ‘natural’ quality among the things growing in them, even in formal gardens. Some gardens and parks accentuate this natural element, perhaps in deliberate contrast to surrounding urban areas. This fosters an impression that the plants, shrubs, and trees have grown where they are of their own accord, and in their own way, regardless of any horticultural tending they have received. Especially in the West, ‘nature’ and that which is ‘natural’ are seen as what does not readily bear the imprint of human interaction, and as emerging more from its roots than from our planning.

Western gardens and parks may have gates, but often their entrance designs accentuate pubic access, providing a continuity of experience for visitors who may have potted plants or flowers where they live and work. In this sense, these garden and park entranceways draw people in from what is less into what is more. In the process, visitors are likely to encounter familiar though markedly larger and more extensively planted shrubs and trees, many of which do not appear to have been shaped or altered by human hands.

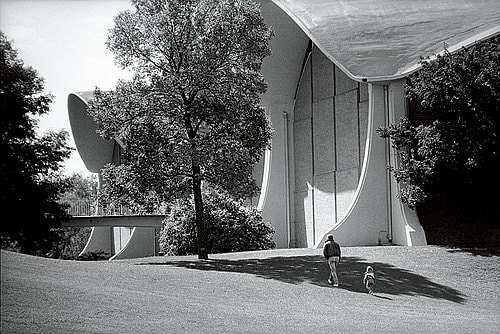

Formal gardens both East and West usually have marked boundaries and even barriers between what is within and that which is outside. Traditional Japanese gardens are typically surrounded by view-blocking walls topped by a ceramic tile parapet. These indicate a formal boundary between the transient outside world of energy-charged daily activity and the stillness available within, where visitors are subtly bidden to release their grasp upon time and their surroundings.

Imposing entrance gates mark a portal to a different realm lying beyond, as much as they appear to provide a barrier protecting what is within. Though these gates and the walls around a Japanese garden may serve to keep out intruders and foraging animals, they exist primarily for the sake of those who enter and take time there. For one does not visit a Japanese garden in the way one might go to a park, as a context to pursue some activity like an exercise walk, but as a place to experience simply being.

In the next post we will continue to explore what is identifiably distinctive about traditional Japanese gardens like the Nitobe Memorial.