If reading this by email, please tap the title at the top to open your browser for the best experience. Then, clicking individual pictures will reveal higher resolution images.

Tiny house on wheels, by designer Haruhiko Tagami

Imagine Frank Lloyd Wright joining forces with Marie Kondo in accepting a challenge to create a tiny house on wheels. This is what Haruhiko Tagami has designed and built for a couple in Japan. Sitting on a single axle trailer frame and weighing approximately 1,300 lbs, Tagami has produced a remarkable example of a miniature F.L. Wright Prairie house on wheels. With its horizontal bands of unfinished lapstrake cedar planking, its recessed corner windows along with those of the light-admitting clerestory above, and clever use of space, the designer of this mobile mini-residence has done ‘the Master’ proud. It even includes a small but efficient wood burning fireplace.

Interior view

A very Japanese feature of this rolling tiny house is the intended multi-use of its principle room as a place for sitting, dining, and sleeping. Backless cushions are provided for sitting, with a table that can be stowed away, especially for night time. Bedding is then brought out from a storage cabinet and spread on a flat surface just as it would be in a traditional Japanese house. The small structure has a minimalist kitchen at the far end, made larger in feel by the expansive window adjacent to the work area. The clerestory above provides standing headroom for a person over 6′ in height, as well as a 360 degree view of the unit’s surroundings.

The kitchen area

When considering all the amenities built into this tiny house, it is hard to envision how small it really is. And yet it provides adequate room for two people to use for extended trips or as a get-away place in the country. The designer kept the overall result compact and light, suitable for towing behind an average vehicle, and able to be parked (without the vehicle) in a typical parking space. A portable toilet is among the items for which stowage is provided within, though the owners specifically did not want space taken up by even a small bathroom. Public toilets are widely available in Japan, and public bathhouses are easily found in almost every neighborhood or community, in addition to the numerous hot springs facilities located throughout the country.

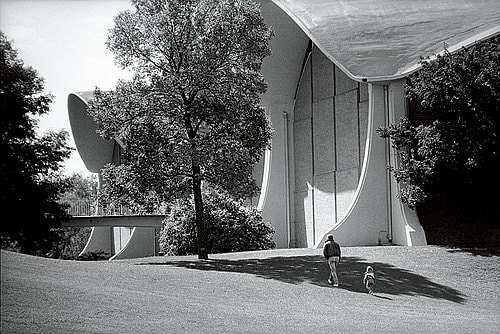

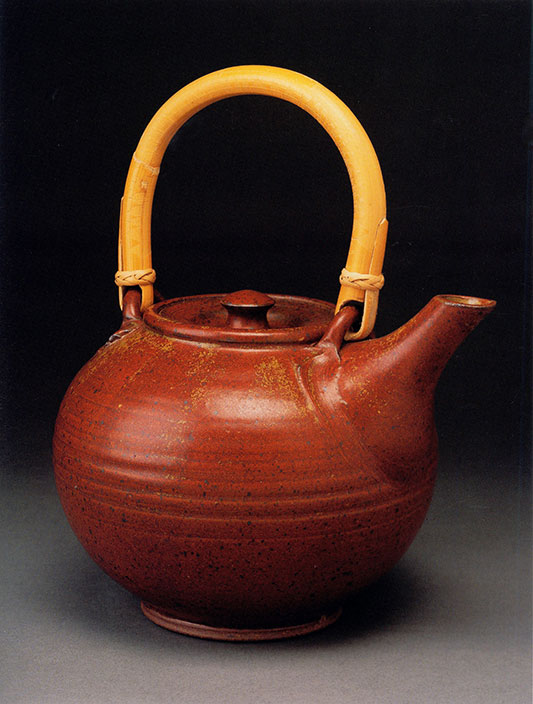

On a larger scale, the Oregon Cottage Company has produced in this country a tiny house they call the Tea House cottage (depicted below). It is built on an 8′ x 20′ trailer frame and includes a formal area for the tea ceremony. Though the exterior of this Japanese inspired example looks conventionally Western, the interior incorporates a number of distinctly Japanese features enhanced by the unfinished birchwood wall surfaces. The windows have opaque shoji screen coverings, and traditional tatami mats cover the floor surface, which contains an aperture for preparing the tea pot. This little ‘tea house’ even provides an enclosed Japanese style soaking tub.

Interior view of Oregon Cottage Company Tea House trailer

Clearly the spare minimalism of traditional Japanese domestic interiors is well suited to tiny house design. These structures provide very attractive places for rest and retreat wherein the beauty of being surrounded by less may contribute greatly to one’s experience of a time away. Imagine – even for a short stay – inhabiting one of these pleasing spaces.