We have many ties with others through birth and our families. We find we are connected with one another by bonds that are not of our own making.

Like the links we have with our families into which we are born or adopted, our relationships with other members of the Body of Christ are also given to us. These relationships are a reality we find rather than one we construct, for they are not products of our acts of willing.

Though we discern the reality of these given birth and baptismal connections between us, we easily fall into patterns of thought that suggest otherwise. When asked who we are, we often answer in ways that ignore these received relationships. We forget that, especially after Baptism, who we are can never rightly be described without also referring to whom we are for.

Acts 2 describes the post-resurrection community as having four shared attributes : common worship, common practices, common goods, and common witness.* Members of this community could share “all things” because they already shared the most important thing, the beauty of new life in the risen Jesus.

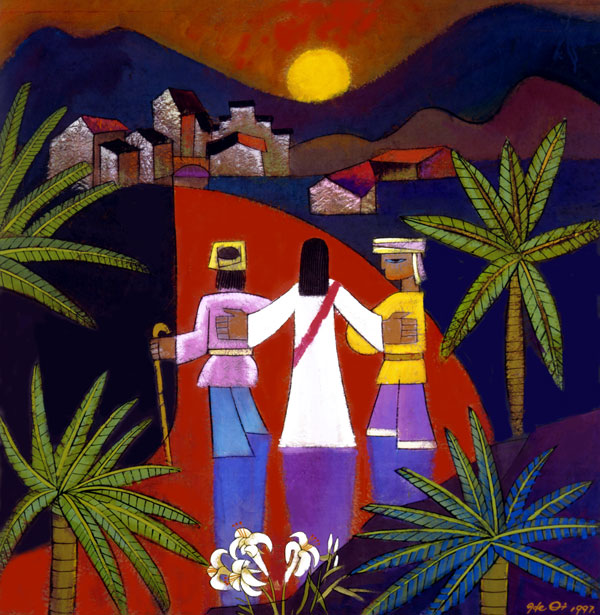

The Rossano Gospels depict Jesus with the disciples at the last supper, reclining in ancient mediterranean style. The image of circular fellowship applies equally to their life together after the resurrection and ascension. They shared their lives at the table of Eucharist and at tables of fellowship, which became visible symbols of everything else they shared.

Judas is shown leaning out from the pattern of this circle, fulfilling Jesus’ prediction about the one who would dip in the bowl after him. Judas’ stance mirrors his refusal to share the common purse with which he has been entrusted, and his disinclination to share common worship and common witness to Jesus’ power among them.

Common beauty is within us and around us. Seeing each other as joined in the risen Lord is directly correlated with seeing the risen Lord in each other. By sharing union with him, and through discerning his beauty in one another, we are more likely to share everything else.

The image above is from the Rossano Gospels, 6th century A.D. *Robert W. Wall offers this insight.