I can’t imagine ever forgetting the experience of holding our first child right after his birth. I’m sure no parent ever does. It was in a hospital in Oxford, England, where midwives assisted Martha. After the birth, they went off to make us a pot of tea, leaving us to enjoy our new baby. What I cannot account for is the mysterious sense of deference I felt toward the Creator in that moment. Not only of profound thanks, of course, but an urge to offer something to God. I believe this feeling is based upon an ancient impulse, latent within our souls. This impulse plays a significant role in the Bible, and particularly in our Gospel for this feast day. All this was made poignant for me when our son, Per, was baptized on February 2, the Presentation of our Lord at the Temple, a few months after his birth.

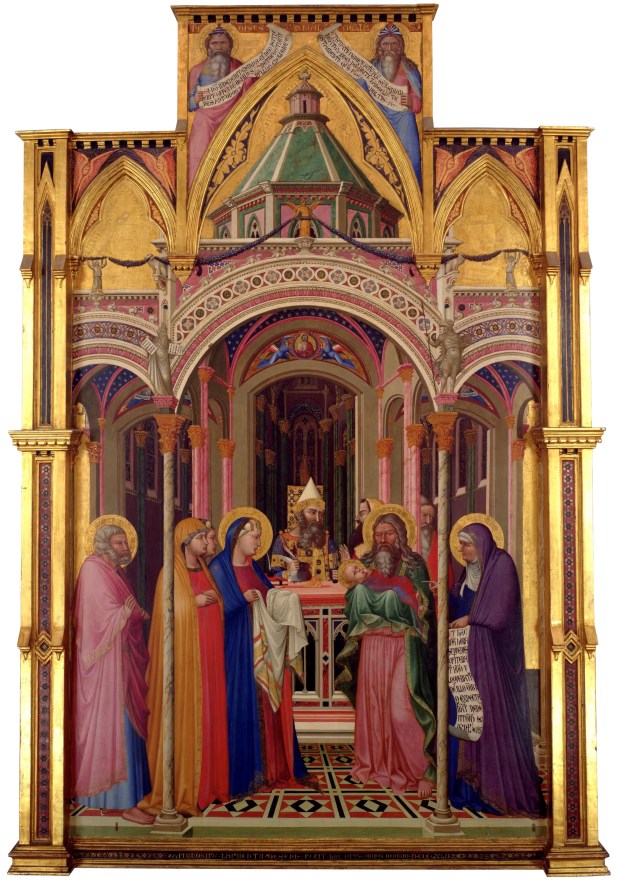

A way into the mystery of the beautiful Feast of the Presentation is to notice how, soon after Jesus’ birth, Mary and Joseph bring him to the Temple in Jerusalem. They present him to the Lord, offering a sacrifice according to the Law. Lorenzetti’s painting of this moment captures the ancient impulse to express thanks for God’s gifts, an impulse that still resonates within us in modern times.

The fuller significance of where the Presentation occurred is less obvious. In Genesis 22, we find a story curiously related to Luke’s story, one that should be remembered as ‘the test of Abraham.’ For Isaac was not actually sacrificed, even though the story centers on Abraham’s willingness to consider it. Genesis says it occurred at Moriah, and tells us that afterwards the place was called “the mount of the Lord.” An Old Testament text identifies the place with Jerusalem, and specifically, with the Temple Mount. In other words, Mary and Joseph take Jesus to the place where God directed Abraham to bring Isaac, the place where God himself provided a ram for sacrifice, instead of a child. And following holy tradition, Mary and Joseph provide a sacrificial offering of thanksgiving for their son in the same location where God himself would later provide another offering for sacrifice. For in Jerusalem, the Son of God, who is the Lamb of God, offered himself as an atonement sacrifice on behalf of the world.

We are not alone in finding the story about Abraham and Isaac, and aspects of ancient cultic practice, unsettling. In Jeremiah, God himself criticizes the “citizens of Judah and the inhabitants of Jerusalem [who]… offer up their sons and daughters to [the god] Molech.” God says, “I did not command them, nor did it enter my mind that they should do this abomination.” Consistent with this, the best way to read the Abraham story is in the context of ancient attitudes and practices. For it was not surprising that a local god should receive the first fruits from the field or flock, or even a firstborn child. The surprising thing in the Genesis story was not that God should propose the sacrifice of Isaac, but that God should intervene to prevent it!

For Abraham, God’s request was like what most gods asked for: ‘give me the first portion!’ But then, God showed Abraham something new: that his faith, trust, and obedience were more important than actually offering his first son. The holy law given to the Israelites showed the same thing. Just like the gods of other peoples, Israel’s God asked for the first portion. But following the pattern God showed Abraham, the Lord did not literally ask for the first child. Instead, He asked for a substitute.

Here is the logic: Since through Creation all things are God’s, God can ask for everything in return. Yet, God asks for only a part – the first part. Asking for the first part is like asking for a symbolic gift: it acknowledges that the whole flock and the whole field is God’s. But as a symbol of the larger part that we get to keep, we offer the smaller part as a token gift to God, from whom all things come. That’s what the offering of the ram was for. It was a sign of God’s kindness that he would ask for a ram instead of a child, and later let poor folks offer doves instead of a ram.

Following this tradition, Mary and Joseph come to the Temple to make their own offering. As is true of all children, their first-born child belongs to God. As a sign of this spiritual truth, they offer to God a substitute for the baby Jesus.

Here we see the mystical connection between the Presentation of Jesus in the Temple, and the meaning of sacrifice in ancient culture. It also helps us see the mystical connection of Jesus’ Presentation at the Temple with what sacrifice means for us and for our future. The first crop, the first lamb, is valued because it symbolizes all that will follow. When God asks us for a tithe, his message is not: “Here, give me a tenth, and I don’t care what you do with the rest!” No! Instead, God’s message is this: “Bring me the first tenth, as a symbol of the nine tenths that also belong to me, but which I give to you. And please use what is left in a way that is consistent with your gift of the first tenth!”

Note: see Luke 2:22-28 to find the Gospel account of Mary and Joseph presenting Jesus in the Temple on the 40th day after his birth. Luke gives particular attention to the appearance of the aged man, Simeon, and of the prophetess, Anna, who play significant roles in the story.