If reading this by email, please tap the title at the top to open your browser for the best experience. Then, clicking individual pictures will reveal higher resolution images.

Peter Paul Rubens, The Rockox Altarpiece, 1613-1615 (center panel)

It is evening on the day of Resurrection-discovery. John tells us that ten of the disciples are hiding behind a secured door out of fear. Judas is deceased, and Thomas is away.

Jesus suddenly appears to the unprepared disciples, and shares with them his peace. He shows them his hands and his side, and then – as a direct consequence of seeing the places on his body associated with his death – the ten disciples rejoice when they see their Lord. In other words, their recognition of him, and that he was somehow alive again, brings them joy by restoring their belief in him.

When hearing this story from John’s Gospel on the second Sunday of Easter, we may be prone to considering it apart from what happens just before it. The disciples, who are hiding out of fear, have already received an eye-witness to the resurrection of Jesus. Mary Magdalene, to whom Jesus revealed himself at the tomb that morning, had come and told the ten the Lord was alive, and that he had appeared to her. Clearly, and prior to Jesus’ unexpected appearance, the ten disciples are still doubting her personal witness. Even after receiving what should have been trusted testimony from Mary Magdalene, a fellow follower of Jesus.

So why – in popular imagination – isn’t this well-known Gospel reading from John 20 commonly referred to as the “doubting disciples” reading? Why should Thomas be singled out, when his joyful recognition of the risen Jesus depended on nothing more or less than what the 10 had needed, and received, before him?

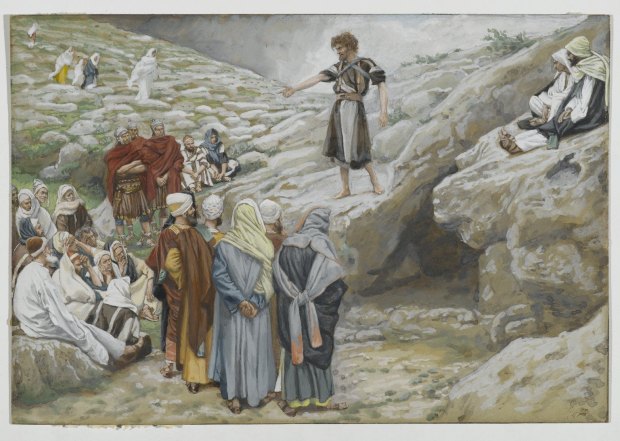

And why have so many painters in the Western tradition privileged Thomas’ purported unbelief in the Risen Lord, rather than depict the earlier reluctance of the ten others to arrive at joyful confidence about the Lord’s astonishing return? Apparently, in many painters’ eyes (especially Caravaggio), more visual drama was to be found in images of a doubter’s hand placed within an open wound.

Caravaggio, Doubting Thomas, 1601 (a famous traditional presentation of the event in John 20)

A further detail to notice, which our familiarity with so many paintings helps to obscure, has to do with how Thomas responds to Jesus. According to John, Jesus appears to the not-yet-believing ten, and – unbidden – shows them his hands and his side. Seeing the traces of his wounds on his risen body brings them joy. Jesus then appears unexpectedly a week later, this time showing himself to the one not present on the prior occasion. And just as he had done previously, Jesus offers Thomas the same opportunity he had provided to the others.

We should therefore not be misled by Thomas’ oft-quoted comment to the other disciples, prior to his own epiphany, about what he needed in order to believe. According to the text, Jesus – upon appearing in the same house a second time – bids Thomas to touch him. Yet, Thomas immediately responds to Jesus’ words without any mention in the Gospel of him having physical contact with the risen Lord’s wounds. Jesus then asks Thomas a rhetorical question, “Have you believed because you have seen me?” Naturally, Thomas’ implied answer is ‘yes.’

For all these reasons, we will do better to find a different and more positive descriptive phrase by which to refer to this well-known passage from John 20. “Jesus meets the disciples according to their needs,” though wordy, would do better.

This post is based on the traditional Gospel reading for the second Sunday of Easter (April 7 in 2024), John 20:19-31. The story within it concludes with these words: “Jesus said to Thomas, ‘Have you believed because you have seen me? Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed’.”

Note: The altarpiece paintings by P. Steffensen and Rubens provide an interesting counterpoint to the prevailing tendency of painters to focus on Thomas placing his hand in the side of the Risen Jesus.