If reading this by email, please tap the title at the top to open your browser for the best experience. Then, clicking individual pictures will reveal higher resolution images.

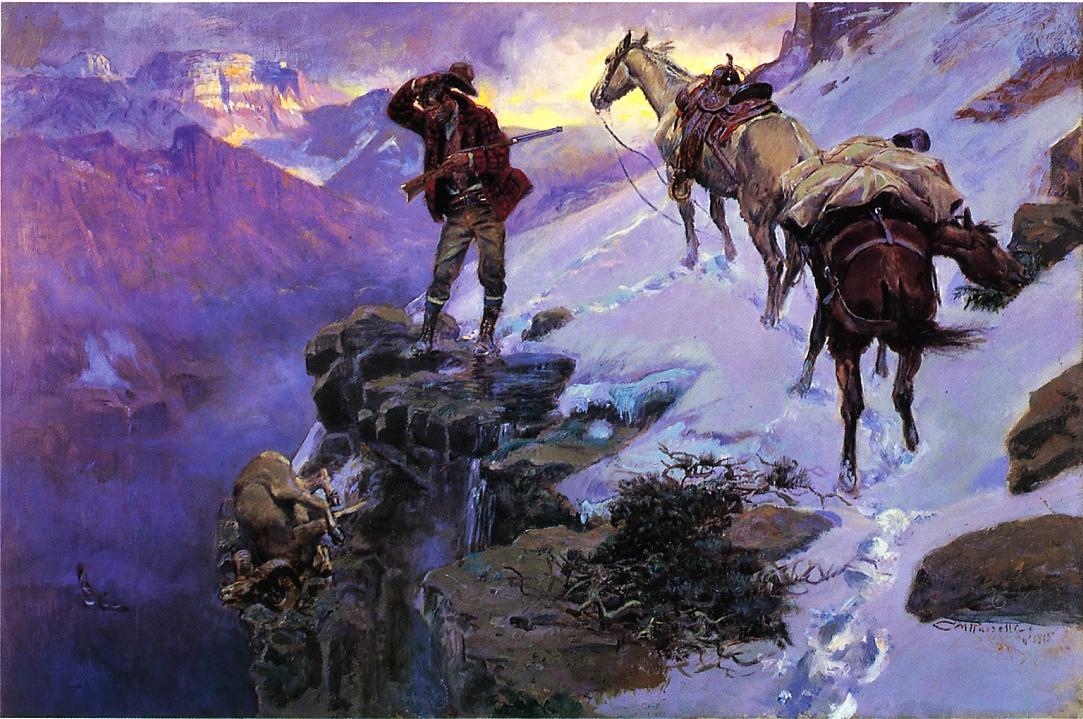

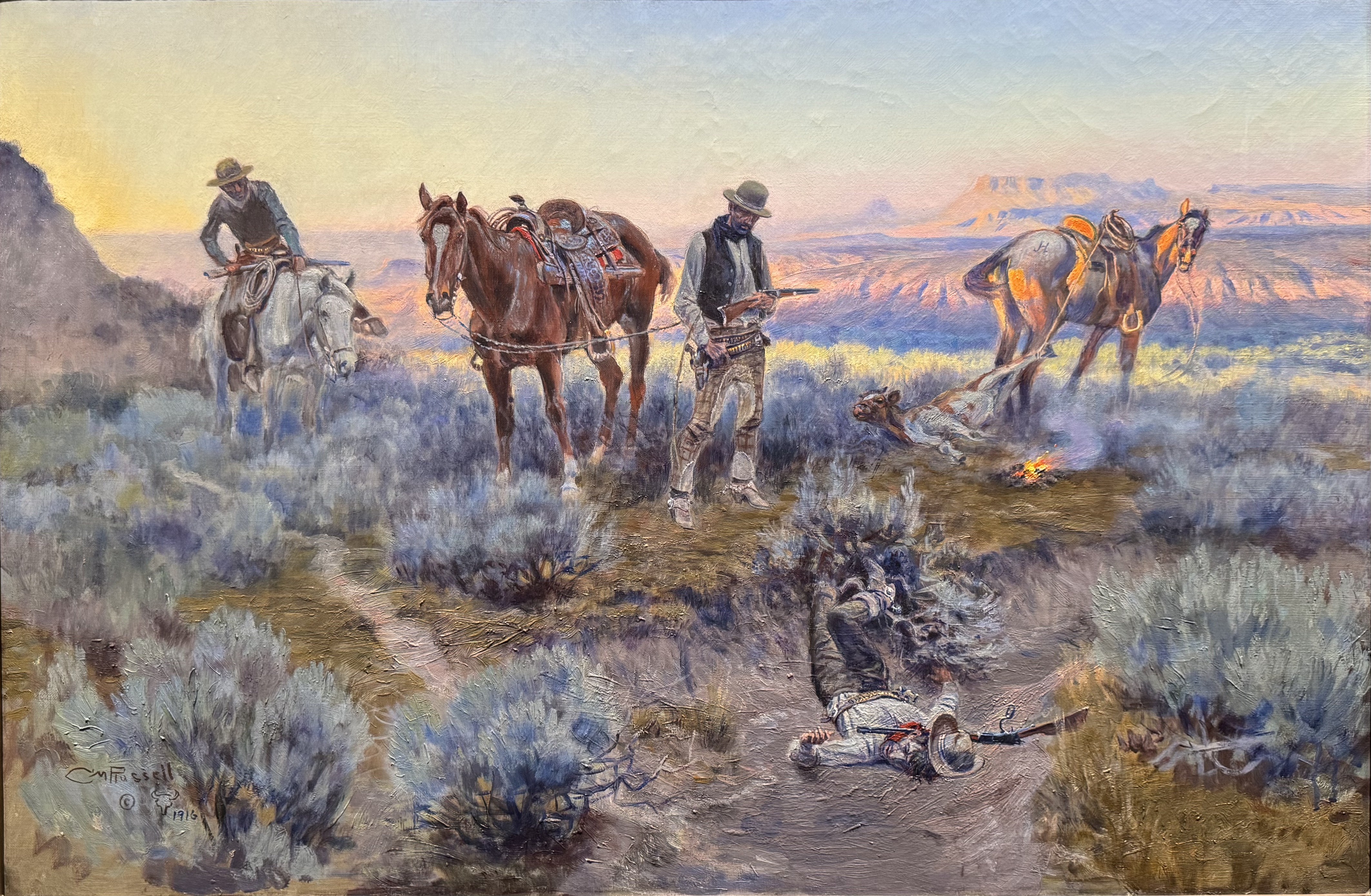

Charlie Russell’s culturally perceptive and action-oriented paintings reflect the social sensitivity that he possessed as well as his visual awareness of the natural world around him. Russell was a much-appreciated story teller, a natural gift that I believe is reflected in his art work. In Charlie Russell’s paintings, we see stories, and many of them represent the climax-point of stories we want to hear.

This raises a significant question regarding the works I am featuring in this post: What distinguishes these Russell paintings from examples like those of James Tissot’s biblical scenes, or Norman Rockwell’s Four Freedoms images? Regarding the paintings of both of the latter two artists, the word illustration may be used without diminishing our regard for their beauty or accomplishment. Yet, and without rendering a judgment about Tissot and Rockwell’s work, there may be a discernible difference between what are technically referred to as illustrations, and paintings that are more properly termed “fine art.”

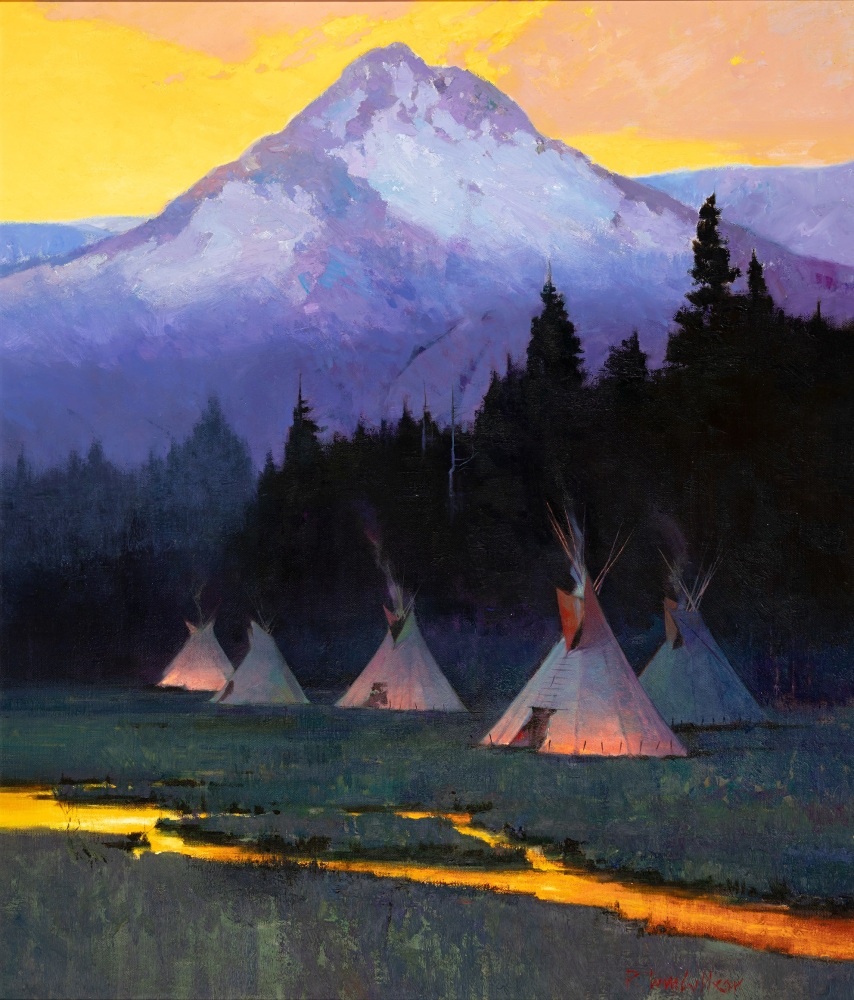

Tom Gilleon’s recent exhibition of paintings at the CM Russell Museum included a personal reflection by the artist regarding his transition from being an illustrator for Walt Disney and NASA, to pursuing painting as a fine art. In that reflection, he refers to an illustrator’s skill in distilling imagery into its simplest forms, for example, by focusing on the power of simple lines and basic shapes. He suggests that, in his transition to fine painting, he pursued those basic shapes and forms as ends in themselves, being aware of how his paintings connect viewers directly to our primal human understanding of such forms. In a statement titled, “Profound Truths in Simple Forms,” he says that “by eliminating all unnecessary elements and being as direct as possible, an artist has the opportunity to guide viewers’ eyes, to tell them stories, to move their emotions.” The Russell paintings I feature here do just that.

Yet, the question remains. What distinguishes fine art paintings from those we call illustrations? If the latter are of a publishable kind, surely they share some of the properties we associate with fine art, and reflect a comparable degree of skill by the artist and a dedication to quality in the results. Building on Gilleon’s reflection noted above, we might say that illustrations are produced to accompany the telling of a story, whereas many examples of fine art paintings do the telling of the story. They do this by capturing more than a particular moment, while being suggestive of the broader context of what has come before, and what might come next. Another way to make the point is this: artworks intended as illustrations generally provide an image of a moment, or a dimension of a story that is communicated by other means, such as narrative.

Yet, in examples of fine art, a painting is meant to communicate on its own, apart from any accompanying text, and sometimes even without a title. In such work, factors such as atmospheric conditions of weather and lighting, or the emotional disposition of any characters portrayed, as well as interaction between them, often play a major role. And the presence and function of these latter elements can significantly determine the effectiveness of a particular work.

In these works of representational art, we begin to inhabit the scene and story, while finding out more about them as we consider the imagery. Russell’s attention to background, the broader context, and surrounding figures, contribute significantly to the overall effect of his work. His very well-known early painting, Waiting for the Chinook (The Last of 5000), provides a reference point for this distinction. As a relatively simple image, its power lies in how it rises above the simple portrayal of a fact, in how it suggests multiple answers to a larger question.

This may help us observe how each of the paintings featured here not only tells a story, but invites the viewer into those stories to imagine what has led up to the moment being portrayed, as well as concerning what might yet happen in the given situation.

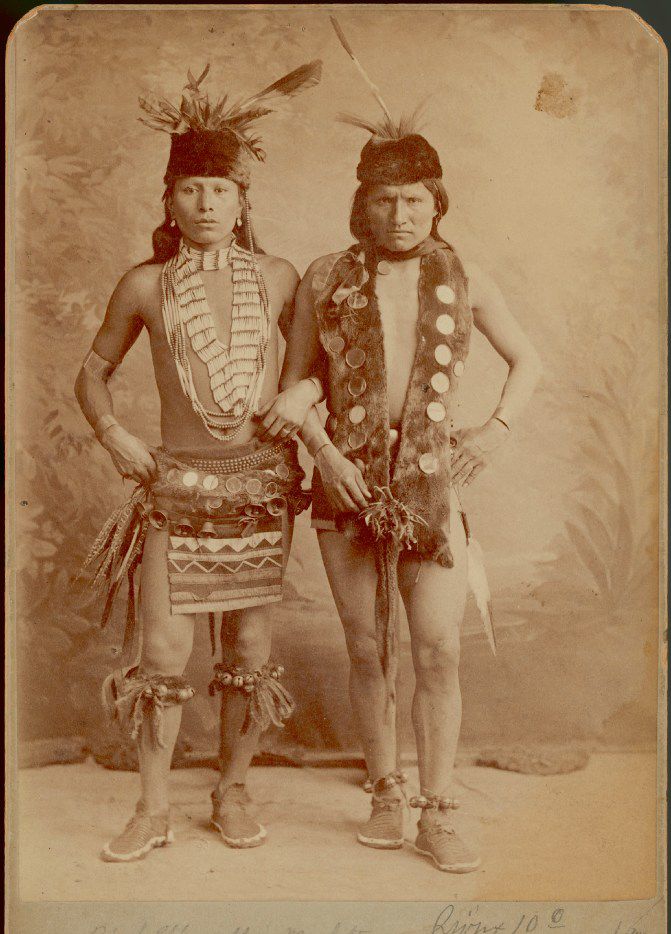

Except for the early Chinook painting (seen above), all of the images included here date after the turn of the 20th century, when the “Old West” had in large part already transitioned from the lore and imagery of the “cowboys and indians” days, an ethos Wild Bill Cody had successfully captured in his eponymous Wild West Show, and was a world soon eclipsed by the emerging film industry.

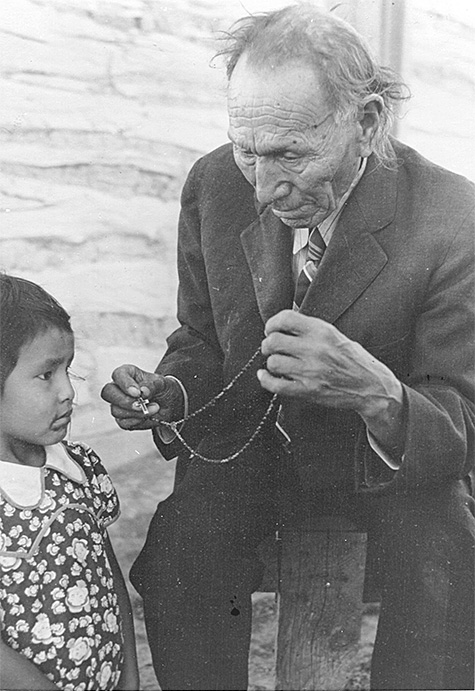

Additional note: Readers may also be interested in the prior post, “Charlie Russell’s Vision of the ‘Old West’.” Once again, I commend a visit to the CM Russell Museum, in Great Falls, MT, to see original Russell paintings and sculptures as well as the artist’s studio and residence, carefully preserved adjacent to the museum. Interior photos of Russell’s studio and home are seen the photo below.