If reading this by email, please tap the title at the top to open your browser for the best experience. Then, clicking individual pictures will reveal higher resolution images.

Le Corbusier, a pioneering contemporary of Frank Lloyd Wright, articulated part of his architectural philosophy with these words, “the house is a machine for living in.” Wright, by contrast, designed domestic buildings more easily described as desirable homes.

Despite Le Corbusier’s modernist statement regarding his approach to design, his Villa Savoye, completed in 1931, was and is once again a beautiful work of what I would call architectural sculpture. This stunning and now restored project has the distinction of having been France’s first modernist building officially designated as an historical monument.

The adjective “iconic” may be overused in contemporary social culture, but the label fits Villa Savoye. So memorable are its lines, curves, and stunning white exterior, that the building has inspired both architectural model kits, as well as two notable tribute structures. The better known of the latter two was an installation by the Danish artist, Asmund Havsteen-Mikkelsen, in a fjord (below).

Another work inspired by Villa Savoye is an almost exact reproduction, but an ‘antipodean shadow’ of the original with its dramatically contrasting black facade (see below). Set in the Southern Hemisphere, it was created as an academic building, a purpose for which Corbu’s design might have been more suitable:

Ashton Ragatt McDougal’s building for the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islander Studies, Canberra, Australia

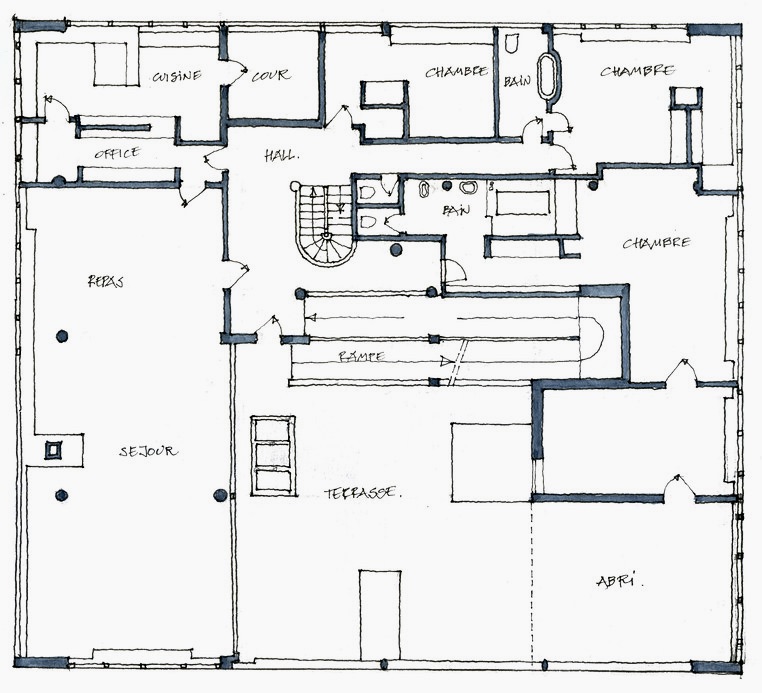

A recent rendering of the plan for the main floor of Villa Savoye

Comparison with Wright’s houses is apt in another sense, for both Le Corbusier and Wright gained well-deserved reputations for prioritizing innovative design features before relying upon time-tested construction methods. One result was that Villa Savoye, like Wright’s famous Wingspread in Wisconsin, suffered from leaks. Leaks throughout the house bedeviled the Villa’s first occupants. While I join others in admiring the formal and visual beauty of Villa Savoye, its practical suitability for a home is questionable.

For me, Villa Savoye’s kitchen focuses the ‘livability’ concern (see photo below). Imagine using this room to prepare aesthetically pleasing meals. This kitchen is not likely to inspire cooking a festive Christmas dinner, looking as it does like an industrial food preparation area. Instead, with the kitchen’s inadequate lighting, I think the expansive windows looking out and away from this part of the building are more likely to attract a cook’s interest.

Yet, Villa Savoye has long been an object of fascination for many architects and members of the public, especially with its marvelous facade where the structure appears to float above the site. In sharp contrast to F.L. Wright’s consistent effort to situate his houses within their locations, employing local materials and integrating the structures with their settings, Le Corbusier set Villa Savoye on the site, just as a classical statue might be set up on a pedestal in the context of a formal garden. All natural landscaping has been cleared well back from the structure, which stands upon the billiard table-like surface of a trimmed lawn.

This deliberate juxtaposition of the building and its setting, where the structure’s design elements contrast so deliberately with the surrounding environment, visually marks the Villa as functioning more like a sculpture rather than as a practical dwelling place. The most successful parts of this house, and perhaps the most beautiful aspects of its design, may actually be those least suited to enhancing actual domesticity. These include the curving walled stairwells and ramped walkways, attractive transition zones through which the residents simply pass.

The main floor’s atrium-like terrace, as well as the curving wall elements on the ground and roof levels are immensely appealing to look at. They draw attention to themselves as objects of visual interest as much as they function as places in which to spend time. Yet, it may be ironic that these are primarily exterior parts of the building.

What I have characterized as the sculptural quality of this building is also evident from the vantage point of the principal living area (see below). This living room strikes me as austere rather than as compelling. Despite its modest fireplace, the room might be better imagined as a gallery space – especially for small scale sculptures – than as a room in which to relax with family or friends. As designed, it and the rest of the house may have been theoretically suitable for its location in north central France, but it is hard to imagine the large room, with its original pre-modern windows, being comfortable on a hot day or during the winter without a modern and adequate HVAC system installed (steam radiators are still evident).

Le Corbusier clearly loved and felt at home on the southern rim of France, in the Cote D’azure, and may have seriously misjudged the suitability of this building for the north central region of his country. But there it sits, no longer a home, and now once again an object for all to admire.

Though I have indicated the likely reasons why I would not want to live in Villa Savoye, I am delighted that the building has been preserved as a focal point for our appreciation of modernist architecture and the International Style. The photos below indicate how near this beautiful place came to demolition after abandonment by its frustrated owners, and its subsequent abuse during the Second World War.

Additional note: Readers who are intrigued by this stunning building may wish to become familiar with some of Le Corbusier’s other notable projects, including his chapel at Ronchamp (featured in a prior blog post), his Marseilles block building, and his theoretical Modular system intended to facilitate human-scale architectural design. The latter may have been inspired by Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, reimagined in a metric system of measurement. The following image demonstrates the way in which Le Corbusier’s modernism was in part based on mathematical theory, and how it played a role in his design for Villa Savoye.

Special thanks to my daughter in law, Laure Le Coq Holmgren, for helping me with the French terms for aspects of Villa Savoye’s plan, and for the correct pronunciation of the building’s name.