If reading this by email, please tap the title at the top to open your browser for the best experience. Then, clicking individual pictures will reveal higher resolution images.

Pottery and the wider field of ceramics represent an historical art form focused on the production of useful objects even when they are prized and collected for their beauty. This wide area of engagement with clay, and with products made from clay, is now fully a part of the Fine Arts curriculum of most college art departments. An evolution in the practice of ceramics from a primary focus upon utility to an unhindered exploration of the possibilities inherent in the medium was surely a logical result of two things. First, there has been a significant increase in the number of practitioners who work with clay out of a sheer love for what can be done with it, and who have pushed beyond traditional parameters of the art. A second factor has been the general influence of the ‘modernist’ trend in the fine arts, encouraging painting, sculpture, and printmaking to transcend representation. This has yielded such recognizable examples as abstract expressionism in painting, and more broadly what has been called ’conceptual art.’ I have touched upon an example of this broad transition in my prior posts featuring the work of David Shaner.

Given my appreciation for Shaner’s work, we visited the Archie Bray Foundation in Helena on a recent trip to western Montana, where he had been a resident artist as well as the Foundation Director. The Bray, as it is now known, will celebrate 75 years of service in 2026 as a non-profit center for the support and promotion of the ceramic arts. It provides studios and technical facilities, as well as residential fellowships, enabling aspiring ceramicists from across our country and beyond to pursue and develop their artwork. Visitors are welcome to come and see the well-equipped studios while engaging with the resident artists, view and purchase examples of work created at the facility, and explore the grounds of the historic brickyard.

In its early days, the Archie Bray Foundation was associated with the pursuit of ceramics as an artform influenced by both western and eastern folk art traditions. Particularly influential in this regard was a visit to The Bray by the English potter, Bernard Leach, and Japan’s Shoji Hamada, later designated as a Living National Treasure by the Japanese government. Leach and Hamada’s presence at The Bray in 1952, along with that of the Japanese philosopher and art critic, Soetsu Yanagi, encouraged attention to the aesthetics of the Mingei tradition of Japanese folk art. David Shaner numbered among those receiving significant creative inspiration from this influence.

The Bray is situated in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains on the western edge of Helena, in a setting incorporating an attractive blend of historic and modern buildings. While visiting this center of creativity, Martha and I met and were able to visit with a young woman named Lexus Giles, from Jackson, Mississippi, whose home is just a few hours north of our own. Her work epitomizes that of many of her fellow artists in residence in her exploration of ideas and forms unique to her own imaginative vision. This reflects The Bray’s laudable encouragement and support for resident artists, for periods up to two years, freely to pursue artistic work reflecting their different backgrounds and particular interests.

For Lexus, this means the opportunity to explore aspects of African American culture through experimentation with the tradition of making face jugs or face vessels. Lexus explained this relatively unfamiliar art form as having origins in the Carolinas among enslaved people, who may have had access to clay and a simple means of firing it, and who used the results to mark graves when headstones and the like were impossible for them to acquire.

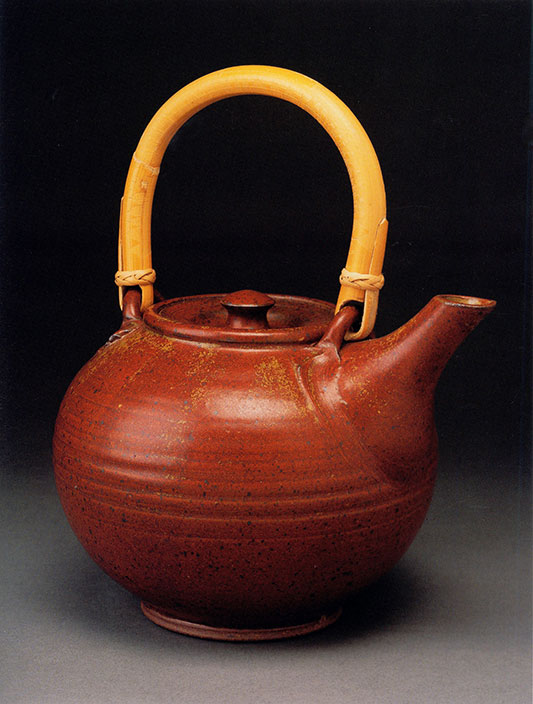

While we met and were able to learn from Lexus Giles about her work, we also appreciated the opportunity to view ceramic creations by other resident artists at The Bray, displayed in a gallery in the administrative building. Some examples are featured in the photos below.

We came away from our visit at The Bray impressed with the quality of the work by the resident artists, and by the positive atmosphere of creativity evident in the studio spaces. Visitors are welcome to the facility and to tour the studios without an appointment, and to walk among the remaining structures within the former brickyard. Back when I was an art student, The Bray is just the sort of place where I would like to have had the opportunity to pursue my interests and develop my skills.

Additional note: Those interested in learning more about Lexus Chiles may wish to see the following brief biography that is posted outside her studio at The Bray.

Once again, in anticipation of this coming Lenten Sunday, I offer a homily I prepared in a prior year, which may be accessed by clicking here.