If reading this by email, please tap the title at the top to open your browser for the best experience. Then, clicking individual pictures will reveal higher resolution images.

This past weekend, with the temperature in the lower twenties and lake-effect snow in the air, I had a chance to revisit a favorite sculpture, Calder’s La Grande Vitesse. Sitting on a plaza in downtown Grand Rapids, MI, the sculpture is notable for being the product of the first award granted by the National Endowment for the Arts for a work of public art, with the project dedicated in 1969. It is a stirring example of Calder’s large scale ‘stabiles,’ as distinguished from his better-known mobiles. La Grande Vitesse may be his most successful work in the stabile category, a grouping which comprises several monumental compositions of welded and bolted sections of steel, often painted in Calder’s favorite vibrant and warm bright red.

Because it is lyrical and engaging, La Grande Vitesse has the pronounced effect of drawing the viewer in to engage with the artist’s vision for the work, both visually, spatially, and even in a tactile way. Sculpture is by definition three-dimensional, in that works of sculpture comprise shapes and forms, whereas painting and drawing typically involve two-dimensional images, whether representational or abstract.

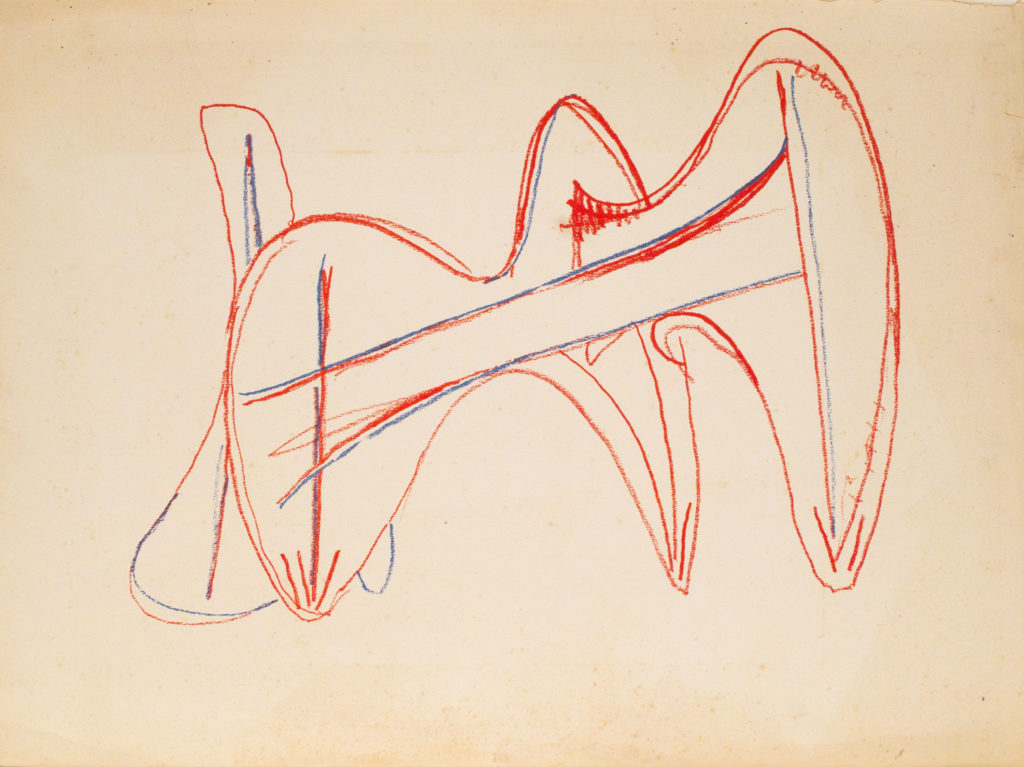

Two concept drawings of what became La Grande Vitesse

Although some painters in the modern era have pushed against the distinction I have just offered (regarding multiple dimensions) by their manipulation of the surfaces of paintings, sculpture remains distinctively in a sphere of its own. You can look at the back of a painting, but you move around (and sometimes through) a work of sculpture – something manifestly true with Calder’s stabiles. Whereas a viewer can encounter a painting through visual apprehension and imagination while standing before it in even a small room, a visitor encountering a sculpture – especially a large one – engages with it as an embodied being, interacting with another object occupying a shared space within a common area.

This helps us notice how the location of a sculpture can make a difference in our appreciation of it. With its stunning color and soaring curved surfaces, Calder’s La Grand Vitesse commands the plaza upon which it rests and would be much diminished if placed in a dark and cramped alley just wide enough to accommodate its size. Therefore, when sculptures are beautiful to behold, stirring in their effect, and well-placed, encountering works of this kind can provide a profound, whole body experience. In this respect, sculpture has an affinity with architecture.

What sets La Grande Vitesse apart from some of Calder’s other large stabiles is the extent of the quality of mystery he created by increasing the number of vantage points required in order to get a sense for the shape of the whole. This, then, extends the time it takes to gain an appreciation for the dynamic interrelation among the sculpture’s parts. Not all examples of sculpture merit the observation that when progressing to each new vantage point, the work appears to be different from one’s prior impression of it.

A second distinguishing aspect of La Grande Vitesse connects its formal title with the name of the city in which it has found a home. Grand Rapids is named for a historic feature of the river it straddles, and the sculpture’s French title can be translated with roughly the same two words. Guides also explain that La Grande Vitesse may properly be rendered as “the great swiftness.” These related names for the art work and its alluvial location fit well with its fluid lines, curves, and protruding fin-shaped panels, which would be at home in a marine environment. For me, the masterful conjunction of the scupture’s multiple curved surfaces accentuates the allure of the work, a sculpture that I find simultaneously uplifting, joyous, and very pleasing to behold.

A 1:5 intermediate maquette of La Grande Vitesse bearing Calder’s signature and date

A 1:23 interpretive model for the sight-impaired (placed on the plaza near the sculpture in Grand Rapids)

Additional note: Placed next to civic buildings designed by Skidmore, Owings and Merrill, the Calder commission to produce La Grande Vitesse for the City of Grand Rapids was part of a larger project – as in so many cities during the 1960’s – to transform the heart of an urban area with what was then sometimes euphemistically called a process of ‘renewal.’ The photograph below of the 1969 dedication ceremony is revealing in that much of the area surrounding the sculpture plaza has since been covered by useful but not always beautiful government and commercial buildings, as well as a new medical center connected with Michigan State University, adjacent to extensions of an interstate highway.