[If reading this by email, please tap the title at the top to open your browser for the best experience. Then, clicking individual pictures will reveal higher resolution images.]

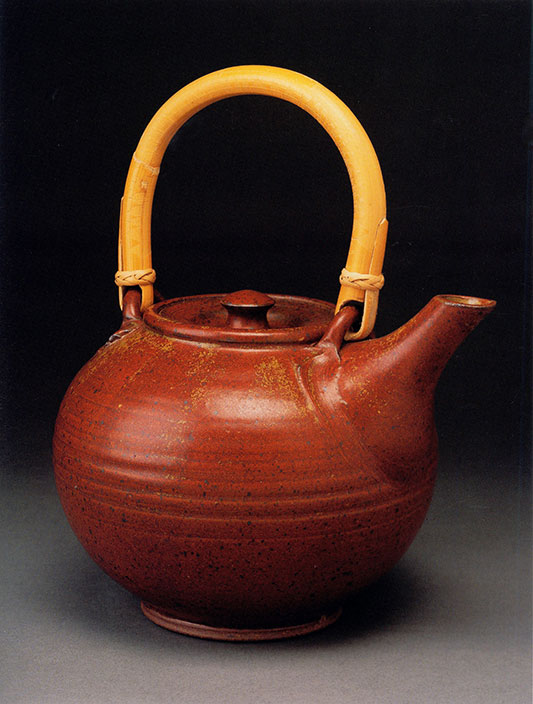

David Shaner, Tea Pot {Japanese style, 1977), with Shaner’s Red Glaze

Shaner’s Red is a polychromatic glaze named after the potter who first applied it to many of his pots. I became familiar with Shaner’s Red on extended visits to family friends who had a pottery studio and a kiln for firing clay at their ranch in Montana. My parents had met them on a ship returning from Japan, where our friends had pursued their interest in traditional ceramics. In addition to throwing pots, they collected a range of examples of ceramic artwork including Asian and Native American, as well as contemporary work by David Shaner and others associated with the Archie Bray Foundation, in Helena, MT. As a youth, I found the color of Shaner’s red and sometimes green and gold glaze alluring, in part because of its variability during firing. In addition to buying assorted mineral and other glaze components, Shaner also gathered found ingredients for his glazes much like weavers often gather natural materials for dying wool.

One brief biographical statement offers this tribute to David Shaner: “His exquisitely formed vessels with their understated glazes are a reflection of the man himself, a man in harmony with his environment and at peace in himself. Shaner was also noted as a teacher, a collector, and a generous contributor to the world of ceramic art and the field of environmental protection; his gardens which he called his ‘spiritual work’ included notable specialized collections.”

Among those who pursue the art of pottery, the color known as Shaner’s Red is a familiar reference point for glazes applied after a first firing of shaped raw clay. Though the red coloring is largely due to iron oxide being in the mix, this glaze by David Shaner is well known for the way it often morphs into other colors during the firing process, with beautiful results. A canister style pot by Shaner (below, 1988) displays this color variability, which is to some extent within a ceramicist’s ability to manipulate while yet retaining an unpredictability that is often a feature of this art form.

Some examples, below, of pots by other artists displaying something of the range of colors yielded by the application of Shaner’s Red.

Here is one ‘recipe’ for Shaner’s Red: 527 Potash Feldspar; 40 Talc; 250 Kaolin; 40 Bone Ash; 213 Whiting; 60 Red Iron Oxide; 2% Bentonite. The significance of the numbers and the nature of these elements are foreign to me. But they are doubtless meaningful to ceramicists who mix their own glazes. The point in sharing these details is to illustrate how, regardless of the precision involved in finding, measuring, and mixing these elements, the exact outcome of their combination and application cannot be foretold in advance.

Shaner was once asked about this at a workshop he had given. A participant later reported that “his reply was something to the effect that to make it look right, you had to be in the right phase of the moon, hold your tongue just right, call on the correct kiln gods, etc. He was obviously kidding but what he was saying is that this is a tough glaze to work with.” Another potter who has applied the same glaze offers this observation: “… the cooling schedule most affects Shaner’s (and other) iron reds. Shaner’s needs a long slow cool, or firing down, for the red color to resurface…”

Having introduced what is perhaps Shaner’s most widely-known contribution to contemporary American ceramics, his eponymous glaze, I plan in a subsequent post to share further about him and provide additional examples of his pottery, especially in light of his later transition from traditional pot making to what is more properly termed ceramic sculpture.

David Shaner in his studio (1989)

David Shaner in his studio (1989)

The photos behind him appear to include one of the esteemed Japanese potter, Shoji Hamada, at work on a pot (upper right). Another photo (top right) features an example of Shaner’s own work that is clearly influenced by the Japanese folk art tradition (the tea pot illustrated above).